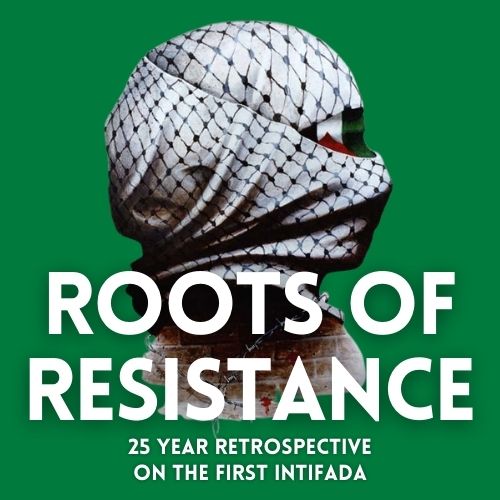

This post is part of the series “Roots of Resistance: 25 year retrospective on the first intifada.” Read the entire series here.

Twenty-five years ago, I had never visited Palestine. It was, I knew, the land from which my father’s family had fled in 1948 and to which they dreamed of returning, but I had only a dim sense of its history, identified only vaguely with its cause. In truth, it seemed then like a lost cause, less a movement than a prayer, recited reverently – sometimes pleadingly – by those desperate enough to believe in miracles. As a college freshman in the United States, born with the right to a shiny blue passport, I had no experience of such despair and little use for such nostalgia. The comfortable, secure life my parents had built for us in America gave me the privilege of selfishness – to be absorbed in my own ambitions, to dream my own dreams.

And then the first intifada burst into the headlines, and I found Palestine, the way, I suppose, that some people find religion. As is often the case in this never-ending conflict, it was the other side’s over-reaction that initially drew me in – not only the brutality of Israel’s efforts to repress demonstrations by unarmed protestors in the Gaza Strip and West Bank, but also the tirade of furious responses to a little letter I wrote to my college newspaper raising questions about Israel’s conduct. I was challenged to a debate “one-on-one, no press” by the president of the campus AIPAC chapter and, as a shocked Jewish friend later told me, labeled a “voice of anti-Semitism” at a Hillel gathering.

But while the ferocity of that response caught my attention, what kept it was the way that Palestinians in the occupied territories conducted themselves as the intifada intensified – and the values their conduct proclaimed. Their renunciation of arms linked Palestine to the non-violent civil rights and anti-colonial movements that I had learned to revere; it illuminated not only the disparity in power between Israel’s occupation forces and Palestinian civilians, but also the moral force of Palestinian demands for freedom and equality. The solidarity Palestinians evinced – their use of grass roots networks to organize strikes and demonstrations, their recognition that women had crucial political roles to play in the struggle, and their insistence on sharing the burdens of resistance across society – revealed a sense of agency that was, for me, both humbling and empowering. Palestinians were doing more than seeking recognition of their right to self-determination; they were taking action to claim their own future.

As never before, I felt proud to call myself Palestinian, to make a cause that had seemed lost my own. I visited relatives in Egypt and Jordan and caught a first glimpse of Palestine from across the Dead Sea. I began to take courses in Middle East history, eventually making it one of my majors, and interned over the summers for the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee and the Palestine Human Rights Campaign, becoming friends with smart, inspiring activists from across the country. With a classmate, I established a student organization, Students for Middle East Understanding, and we convened teach-ins, built coalitions with other progressive groups, and blanketed campus with red, white, and green flyers (which often, by the next day, were themselves blanketed by blue and white ones). And, in my senior year, I wrote my thesis on the Palestinian-American immigrant experience, spending hours each week doing “fieldwork” (i.e., having long conversations over plates of hummos and pretzels) at the Palestinian community center on the South Side of Chicago. There, I met kids whose parents came from the West Bank and who had spent their summers demonstrating in Ramallah and Bethlehem. I listened to their stories with a mixture of admiration and envy, hoping they would see me as a fellow traveler, rather than a tourist. Palestine, I was coming to see, was not just a place, not just a cause, but also a community.

As other contributors to this series have described, the first intifada transformed the political landscape in Palestine and Israel, and it was a lightning rod for advocacy around the world. But the transformations it effected were no less personal than political. For many of us who had never visited the Holy Land, the intifada brought Palestine home. It was our introduction, our initiation, our gateway to an addiction that I suspect few of us have managed to kick.

Of course, much has been lost since then. By the time I graduated from college in 1991, the intifada had already been eclipsed by the first Gulf War, marred by intra-Palestinian violence, and thrown into disarray by the arrest or assassination of many of its leaders. And, in ensuing years, we have seen Palestinian land swallowed by Israeli settlements, movement halted by checkpoints and walls, and solidarity sapped by disunity and disappointment, as popular struggle was replaced by an interminable negotiation process, and patronage was substituted for participation. Looking back, it is hard not to feel that the cause has lost its way, difficult not to regret the path not taken.

But lest we succumb to the paralysis of nostalgia, it bears remembering that Palestine has never been one cause, never one path. It has always been a struggle not only for national self-determination, but also for individual rights (initially land rights, and later refugee rights and other civil and political rights), as well as a front in broader regional and international struggles (like socialism, Arabism, and political Islam). These paths at times have seemed to converge, but they have never led to the same place. Twenty-five years ago, Palestinians could march together without confronting many of the choices that divide us, but difficult choices abound. In a world organized into sovereign states, can Palestinians achieve freedom and equality in our homeland without a state of our own? Is refugee return compatible with a two-state solution? Is it conceivable without one? Can a national liberation movement be sustained without nationalism? Can a bi-national civil rights movement succeed despite it? And can the Holy Land be transformed into a secular political space?

As we stand at the threshold of a new year – and, perhaps, a third intifada – the time has come to confront these questions and, together, to answer them.

taking to palestine the very same way other people find religion?

labeled a voice of antisemitism at a hillel gathering?

palestinians were doing more than than seeking recognition of their right to self-determination, they were taking action to claim their own future? –

like palestine, just & free?

+ peace on earth

goodwill to all living beings

A very thoughtful and insightful article which I must admit, as a Palestinian, can relate to very much. I think the questions you raise in the end overshadow what romanticism there is, there was or there ever will be over the struggle to liberate Palestine( what’s left of it). In the cold war era, the struggle played out it’s anti-colonial anti-imperialist theme. The news of the Berlin wall falling seemed to have never reached Israel. The new world order after the collapse of FSU allowed for the conflict to be domesticated. The hired revolutionary guns on the international arena saw their safe havens behind friendly Arab regimes no more and hiding behind the iron curtain for protection was no longer an option as well. Their funding had dried up and time for a new paradigm shift. On the home front in Palestine, impatient with the lack of progress to end the occupation, kids in Ramallah took matters in their own hand – literally, to give birth to the first Intifadah, broken bones and all. Those two factors, the PLO being financially broke to irrelevancy and the natives getting restless enough to where the occupier sought out a less costly occupation gave birth to Oslo.

So, back to the most important question you raise, at least for me, as I have often wondered myself if not the land is cursed – maybe the land itself is the problem. All the historical biblical mythological baggage that comes with the “Holy Land” inherently invites the crazies. Is there space for a secular state – put aside the question if it is democratic or not – Jewish or not – can a normal secular state ever stand in the “Holy Land” against the enormous gravitational pull of its religious past – the cries of it’s mythological forefathers and as we see today, it’s current holy warriors on both sides?

This conflict in my view is insoluble short of Armageddon. If Israel was a true secular state, this conflict would have been resolved by now. When your negotiating partner uses the Torah as exhibit A in their arguments; when discussing Jerusalem, the retort of Zionists is to point out the number of times in the Torah Jerusalem is mentioned, as somehow this is rational, you just have to shake your head in disbelief.

History, real or not, biblical or mythological, will repeat itself. No getting around the fact, those who are shaping history are the religious crazies. With their “Pillar of Cloud” operation and “Sampson Option” in hand, not hard to figure out where this is going. Everything else is background noise. The Palestinian’s role in shaping that history is negligible. They are hapless pawns twirling in a perpetual man made geopolitical storm.