Shapira and Neve Sha’anan neighborhoods are not the White City of Tel Aviv guidebooks. Although central, bordering the main bus station, these are the parts of town where cracks in concrete are not fixed, and certain streets are avoided on warm days because of a stench of urine that never washes away.

To the east of Tel Aviv’s bus station are blocks of African refugees hawking shoes and old kitchenware from soft blankets atop the pavement, which double as storefronts. And on the west side, there are sporadic mid-night Molotov cocktails hurled into asylum seeker’s homes. There are also blue-collar Bukhari Jews and migrant workers, living examples of Israel’s legal and non-legal immigration history. But crumbling between the 1960s era homes and recently fabricated tin structures is a ghost of Israel’s past: a Palestinian mansion only a five-minute walk from the nexus of the city’s transport system.

Dubbed the “Red House” by architects and graduate students at Tel Aviv University, this structure serves as a reminder that Israel’s first city was not built from empty sand dunes. And now the future of the Red House, a marker of four Palestinian villages that were destroyed after Israel declared independence in 1948, may be just as dim as its past. The municipality set to purchase the property sometime this year, which could signal historical preservation or demolition.

Today, the Red House is inhabited by a rotating microcosm of Tel Aviv’s southside population. The upstairs is home to a group of activists from the radical left. On the lower floor is an unregulated kindergarten for refugees and rented flats, where sleeping quarters stretch into a grassy yard.

“My friends in 2006 were looking for a cheap house and found it [the Red House] and then looked in the municipality book and contacted the owner,” said the resident, who wished to remain anonymous. After the young Israelis moved in, they made some repairs to the building but kept the original aesthetic of the building intact. The original wallpaper can be seen in most bedrooms; painted tiles cover almost the entire floor.

The Red House is a “well house,” or a large agricultural home once used by wealthy orange growers. Constructed over 150 years ago, the Red House is one of 60 well houses that remain from the late Ottoman, early Mandate period. But in 1948, these structures were taken over by the Israeli authorities, and eventually, many were abandoned. When the activists found the Red House of Shapira, it showed signs of renovation from approximately 40 years ago but looked more like a heroin den than a lavish home. And one room had damage from a fire.

“This kind of thing was popular in the 70s and 80s, this kind of disgusting painting,” said one of the activists, pointing to stucco in what is now his bedroom. New walls added during the previous renovation period cut in extra rooms, including bathrooms. “It was the only house in this area,” he continued. “People say they must have been a rich family to have such a house.”

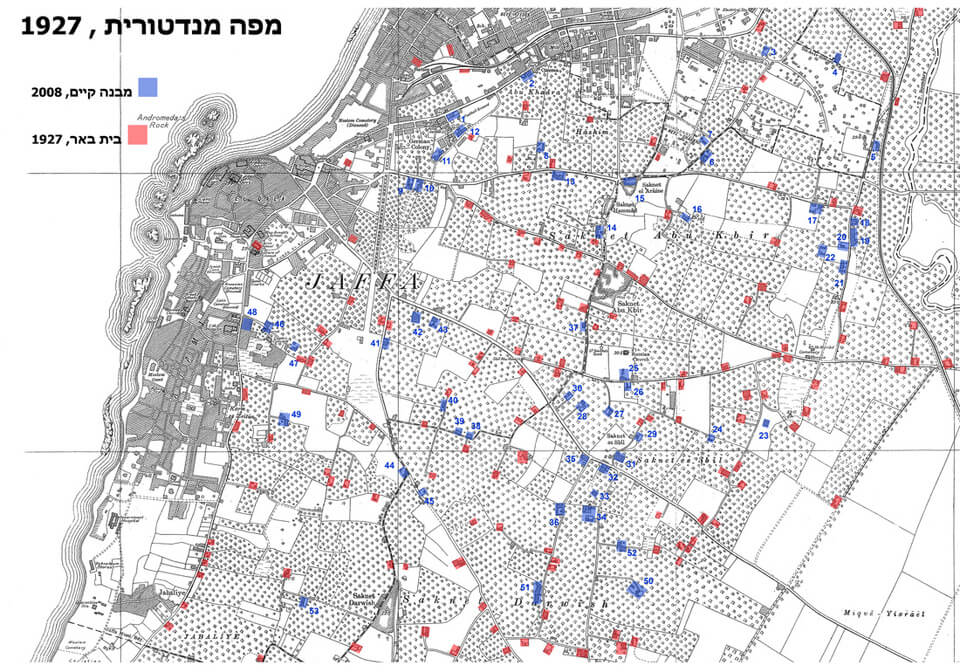

Around the same time, as the activists moved into the Red House, professors, and graduate students at Tel Aviv University’s David Azrieli School of Architecture also came across well houses in the south part of the city. Under the direction of Naor Mimar, Amnon Bar Or, and Sergio Lerman, the team published a report in 2007. They documented that before 1948, Tel Aviv and Jaffa boasted around 200 of these structures, but today, only some 60 structures remain.

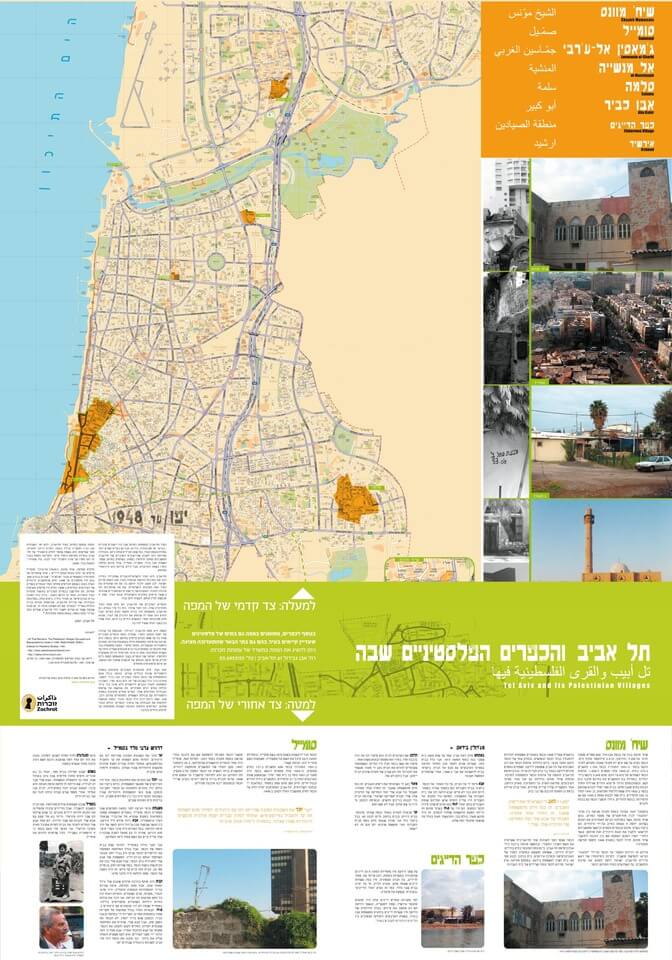

Concurrent with Tel Aviv University’s research, Zochrot, the Israeli organization dedicated to remembering the Palestinian nakba, or 1947-49 displacement, also mapped out Palestinian sites in the Jewish city. Zochrot then attempted to contact the original owners of the Red House. Through their research, they were able to uncover the Murad family once lived there, and during the nakba, they fled to Jordan. The organization has since tried to track down the original owners but to no avail.

When looking at the final mapped results of both Zochrot’s and Tel Aviv University’s pinning of former Palestinian houses, it becomes clear that the capital of Jewish culture in Israel/Palestine was not a virgin land. On the contrary the well houses show the area was fertile agricultural land with the canonical empty sand dunes of Nathan Gutman paintings only on the open coastline. Four Palestinian villages (Salama, Shaykh Muwnnis, Jammasin al-Gharbi, and Summayl) comprised the southern, central, and northern parts of the city, respectively.

Still, the resurgent interest in the well-houses has not softened the ire aroused by articulating Israel’s Palestinian past. Last April, Zochrot tried to organize a reading of the names of Palestinian sites in Tel Aviv, but police arrested some of the activists and confined others to their offices. Even though the event was forcibly canceled, a mob of Israelis congregated outside of Zochrot’s doors to protest.

Historical preservation and the Red House’s uncertain future

In 2008 Tel Aviv University took their findings on the well houses public. To lobby the city for preservation measures, the researchers held an exhibition that summer. “The goal of the exhibition is to put the well houses on the agenda, so the municipality will not roll its eyes and say they do not merit conservation,” said Bar Or to Haaretz days before the gallery opening. Unlike Zochrot, Bar Or and the research team’s motivations to preserve the well houses were not altruistic to seal a place for Palestinians in this city’s foundation.

“After all, conservation is memory. The cultivation of the Bauhaus heritage has made people forget what is not seen and not preserved. It makes no difference to me that some people claim that to preserve these houses is to anchor the history of the Palestinians,” continued Bar Or.

Even more, students of Bar Or (Oded Bitan, Hila Ron, and Tamar Nativ) arranged tours of a handful of the disintegrating mansions in a city-sponsored event. Annually, the Tel Aviv municipality hosts “Houses from Within,” where architecturally interesting houses open their doors to visitors. Scrolling through the list of previous years’ houses, most are the residences of urban artists, some of which are even former Palestinian homes in Jaffa. But the well houses stand apart from the other listings because they are the only grouping of buildings showcased for the uniqueness of being former Palestinian homes in the heart of Tel Aviv.

By 2012, enough interest was galvanized around the Palestinian homes to prompt Tel Aviv to pass preservation legislation on the well houses. Yet codifying these types of repairs is relatively new to Israel, despite the abundance of historical sites—and state protection for homes specifically because of their Palestinian style is almost unheard of. In 2009 Tel Aviv made a first try to protect historic buildings and passed a comprehensive plan on preservation, which was met with ire by the residents. Effecting almost exclusively Bauhaus buildings dating from the 1930s, houses that qualified were required to have strict restorations at the expense of the owner but with subsidies offered by the city. Following the passage of the law, homeowners in Tel Aviv filed a class action, citing punitive expenses imposed on owners of older buildings. Perhaps this outpour of legal action influenced the city because, in the 2012 regulations on well houses, private residences were exempted.

For the Red House, the loopholes in the policy could either serve as a mandate for preservation or a green light for demolition. The current owner is in the process of selling the house to the city of Tel Aviv, likely ensuring strict renovations. However, the city could easily flip the property to another private owner who could then gut the building of its lingering Palestinian architecture. The original well, decorative wood panels, floors and window glass are still throughout the structure.

But the Red House’s current residents are cynical that preservation will come for their home. A few weeks ago, an inspector from the city came to visit the building, and when one of the activists living there asked about the future of the house, the city employee scoffed that it would likely become condominiums for Tel Aviv’s elite. The Red House residents also are quick to note, “That’s what they did in Meshina,” another former Palestinian area in Jaffa—after the city bought the buildings, they contend, the municipality sold them to a new set of owners who were free to refurbish the buildings beyond recognition. If the house is demolished or renovated beyond recognition, it would erase yet another piece of Palestine’s history in the nucleolus of Tel Aviv. In light of the current circumstances the best scenario is that the house will remain under the stewardship of the city and will be persevered for another generation at least.

But, as of now, one of the activists lamented, “It’s all rumors.” At this time they do not have an exact eviction date, and the city has not provided insight if preservation or demolition will come next.

Fascinating, and moving reminder of the history of this area. What a tragedy that Israel will be only too keen to wipe out the memory of the past, substituting their own fantasy version of pre-1940’s Israel. They have done it all over Israel, after all. Maybe when they mature as a country they will understand the horror of what they have done, and restore a genuine history and dignity to the area and its populations. They want Anne Frank’s house preserved, they want innumerable museums and testimonies to the Holocaust, but a simple, dignified acknowledgement of Palestinian history is beyond them.

Fascinating piece. Great photos. Surely the Red House is an excellent restoration/historic preservation opportunity.

One photo is largely responsible for Tel Aviv’s founding myth. The photo with a group of people (who we are to assume are Jewish) standing in a large group on a patch of desert with sand dunes in the background. Tel Aviv was Jaffa/Joppa. Expanded to a degree, yes but mostly just the Jewish side of a boundary. I might be thinking of something else, but there might have even been a little (pre-Zionist) town there originally with its own name. One of these days I hope somebody will write an extensive real history book about the whole thing so people can see through the mess of propaganda myths.

RE: “Not an empty sand dune: A Palestinian mansion in downtown Tel Aviv” ~ article by Allison Deger

MY KUDOS: A superb, beautifully written article!

As a city, Tel Aviv started in the early 1900s. To be sure, there were individual homes or buildings in the area, including a mosque seen from the southern most part of Tel Aviv beach, before the city began. What else is new? It became an extension of Yaffo, a city of mixed religions. There were homes in Hebron belonging to Jews, well before 1929 and the infamous Hebron massacres against Jews. Ditto in other Palestinian only towns in the West Bank. What’s your point? Thousands of Jews were killed in 1948, a war they didn’t start. I’m sure thousands of Palestinian arabs were killed too, and many formerly arab villages and towns erased. You expect time to stop, only arab claims to be met, and the 6 million Jews of Israel and their histories to be irrelevant? When is MDW and other anti-Israel sites going to accept the reality of a land to either be divided between two peoples, or a very long reconciliation, starting with eliminating obvious anti-Jewish propaganda and the “right” to kick them all out of “their” land, which could one day result in one country serving both peoples equally. At this point in time, it could not work; there would be a horrific bloody civil war. Is that your goal?