The following is an excerpt from the book “Goliath: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel” by Max Blumenthal. You can buy the book here.

There Are No Facts

On December 2, 2010, a burning tree trunk fell into a bus full of Israeli Prison Service cadets on their way to Damon Prison, a detention center described by female Palestinian inmates as “the worst jail ever.” Forty of the cadets were immediately killed by the felled tree, marking the opening chapter of a rapidly unfolding national tragedy that generated an outpouring of anti-government rage that had rarely been seen in Israel. Within four days, hundreds of thousands of trees planted along the Carmel Mountains had been turned to ash, while the outskirts of Haifa were engulfed in smoke. More than 12,300 acres were burned in the Mount Carmel area, a devastating swath of destruction in a country the size of New Jersey.

In characteristically apocalyptic language, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu described the fire as “a catastrophe the likes of which we have never known.” A prison guard who visited the site of the bus accident collapsed in his friend’s arms. “It’s worse than a terrorist attack in Gaza,” he cried. “They just laid there on the floor, dozens of people, and there was nothing to do.”

Netanyahu’s government had confronted the fire with complete passivity. The day after the conflagration began to spread, he informed the country, “We do not have what it takes to put out the fire, but help is on the way.” Having prioritized the procurement of advanced military gear and occupation maintenance over the country’s infrastructure, Netanyahu was powerless in the face of natural disaster.

Forced into a corner, Netanyahu begged for assistance from his counterpart in Turkey, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the man he had accused during the flotilla imbroglio of collaborating with al-Qaeda and Hamas in Israel’s destruction. Next, Netanyahu beseeched the Palestinian Authority, another entity he frequently demonized, for firefighting assistance. Having spent years carping about the whole world being against Israel, Netanyahu found that even those he had labeled as murderous terrorists were willing to help. And his government repaid them with humiliation and disrespect. After the PA sent its most able team to help snuff the blaze, most of its firefighters were refused entry to Israel to attend a ceremony organized to honor their contributions, forcing Israeli officials to cancel the ceremony altogether. In the words of Arab member of Knesset Ahmed Tibi, the incident was “not just a march of folly or a theater of the absurd but stupidity and the normative lordly attitude of the occupation regime.”

The bulk of Israeli public anger focused on Yishai, the Shas leader who headed the Interior Ministry. It was up to Yishai to ensure the viability and preparedness of Israel’s firefighting corps, however, he seemed far more interested in diverting public money into the settlements, especially those that were home to his religious Mizrahi constituents. As he declared in June 2009, “I promise to use my ministry, all the resources at my disposal, and the ministry’s impact on local authorities for the good of expanding settlements.” With his near-criminal negligence exposed and his cabinet post in grave danger, Yishai claimed he was the victim of anti-Mizrahi prejudice, moaning, “What is happening here is a lynching.” Adding insult to injury, the spiritual leader of Yishai’s Shas Party, former Chief Israeli Rabbi Ovadiah Yosef, blamed the fire on the sins of its victims, proclaiming in his weekly sermon, “Fires only happen in a place where Shabbat is desecrated. Homes were ruined, entire neighborhoods wiped out, and it is not arbitrary. It is all divine providence.”

As the circular political firing squad unloaded in the wake of the disaster, with one minister blaming another for a failure that indicted the government as a whole, the Carmel fire inadvertently exposed an open wound at the heart of the country’s character and identity as a Jewish state. The pine trees that had burned so easily across the Carmel mountains were originally intended as instruments of concealment, strategically planted by the JNF atop the sites of the hundreds of Palestinian villages the Israeli military evacuated and destroyed in 1948 and ’67. With forests sprouting up where towns once stood, those who had been expelled would have nothing to come back to. And that was exactly what the JNF intended.

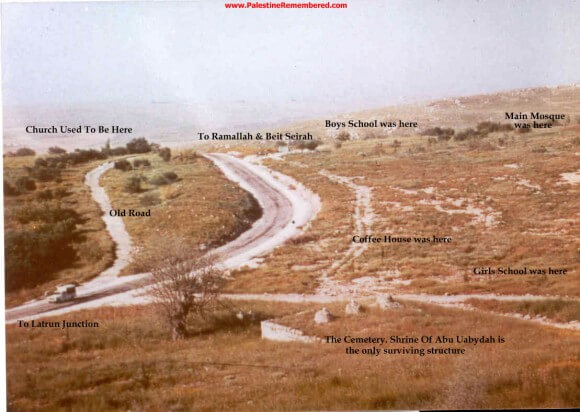

The JNF’s showcase forest, Canada Park, is built on the ruins of the Palestinian villages that once stood in Latrun—Imwas, Yalu, and Beit Nuba. Having failed to remove the villages in 1948, the 82nd Regiment of the Israeli army returned to Latrun in 1967 to finish the job. Besides the desire for revenge after the punishing loss at Latrun in ’48, the state considered the villages an obstruction to building a direct highway from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. At nine in the morning, the soldiers gathered the eight thousand residents in an open area and, with direct orders from General Yitzhak Rabin, ordered them at gunpoint to march to Ramallah. Hours later, bulldozers arrived to destroy the villagers’ homes.

“The chickens and the doves were buried under the ruins,” the regiment commander, Amos Kenan, later recalled. “The fields turned desolate before our very eyes, and children walked down the road sobbing. That was how we lost our victory that day.”

Though some of the enlisted soldiers cried as they witnessed the pathetic scene unfolding before them, none disobeyed their orders to guard the bulldozers. Moshe Dayan reassured Israeli skeptics that the expulsions were conducted “with Zionist intentions.”

During the 1970s, the JNF constructed Canada Park with generous donations from the Canadian government, planting thousands of non-indigenous pine trees on the rubble of Imwas, Yalu, and Beit Nuba. Today the park is an idyllic setting for cyclists, hikers, and families who spend Israel’s Independence Day picnicking in the sun. However, those who venture too deeply into the forest may risk stumbling over the still-intact spring and water wells belonging to the scattered refugees of Yalu, or the rubble of a church where the Christians of Imwas worshipped each Sunday until the Israeli bulldozers sent it crashing to the ground. Though few Israelis realize it, when they stroll in the shade of Canada Park’s pines, they are actually inside a section of the West Bank captured from the Palestinians—that the JNF trees mask the occupation.

Until 2006, the JNF omitted the history of the Palestinian villages from the explanatory signs it posted around the park, instead presenting details of life in the Second Temple, Hellenic, and Roman periods, adhering to a strictly Eurocentric narrative. When Zochrot, an Israeli non-profit dedicated to preserving the memory of the Nakba, petitioned the Supreme Court to amend the signs to include the history of Arab habitation, the JNF first attempted to deflect all responsibility onto the Israeli government before it finally conceded to the demand. But almost as soon as the revised signs were posted, one mysteriously disappeared, while vandals meticulously blacked out the section mentioning Palestinian villages on another.

The JNF was intimately involved in the Nakba, with its then-director Yosef Weitz establishing the Transfer Committee, where a pantheon of leaders orchestrated the final and most brutal stages of ethnic cleansing, which they called Plan Dalet. Described by the Israeli revisionist historian Ilan Pappe as “the quintessential colonialist,” Weitz personally guided the expulsions with a deliberate, calculated hand, dispatching his staff to identify Palestinian villages to destroy—a practice David Ben Gurion called, “cleaning up.” “It must be clear that there is no room in the country for both peoples,” Weitz declared at the time. “If the Arabs leave it, the country will become wide and spacious for us. . . . The only solution is a Land of Israel . . . without Arabs. . . . There is no way but to transfer the Arabs from here to the neighboring countries, to transfer all of them, save perhaps for [the Palestinian Arabs of] Bethlehem, Nazareth, and the old Jerusalem. Not one village must be left, not one tribe.”

In the ethnically pure Israel of Weitz and Ben Gurion’s dreams, a distinctly European, alpine landscape would be able to flourish atop the “wilderness” the Palestinians had supposedly failed to cultivate. Having fulfilled most of the goals of Plan Dalet, namely, expelling as many Arabs as possible and replacing them with new Jewish immigrants, the JNF planted hundreds of thousands of trees over the freshly destroyed Palestinian villages. In establishing the Carmel National Park in northern Israel, the JNF strategically concealed the ruins of al-Tira, a once-populous and picturesque town that joined the hundreds erased from the map. As the trees matured and developed into a full-fledged forest, an area on the south slope of Mount Carmel came to resemble the landscape of the Swiss Alps so closely that Israelis nicknamed it “Little Switzerland.”

But the nonindigenous trees of the JNF were poorly suited to the dry Mediterranean climate of Palestine. Most of the saplings the JNF plants at a site near Jerusalem die soon after taking root, requiring constant replanting. Elsewhere, needles from the pine trees have killed native plant species and wreaked havoc on the ecosystem. And when the wildfires swept through the Carmel Mountains, “Little Switzerland” quickly went up in smoke.

Among the towns evacuated during the Carmel fires was Ein Hod, a bohemian artists’ colony nestled in the hills to the north and east of Haifa. During the great conflagration, residents of the village came pouring out in search of escape, with some seeking shelter in nearby Arab villages. It was not the first time Ein Hod was evacuated. The first time was in 1948, when the town’s original Palestinian inhabitants were driven from their homes.

Before the establishment of Israel, Ein Hod was called Ayn Hawd. The town had been continuously populated since the twelfth century, after Arabs from Iraq settled the area. During the Nakba, Israeli troops expelled most of Ein Hod’s residents to refugee camps in Jordan, Syria, and Jenin in the West Bank. But a small and exceptionally resilient clan fled to the nearby hills, set up a makeshift camp, and watched as Jewish foreigners moved into their empty homes.

In 1953, when the army authorized plans to bulldoze the town, a Romanian Dadaist sculptor named Marcel Janco successfully lobbied them against it. Janco was not acting out of humanitarian concern but self-interest: in place of the Arab village, he proposed establishing an all-Jewish art commune to generate tourism and contribute to the culture of Zionism, which he claimed would benefit from the modernist traditions he had brought over from Europe.

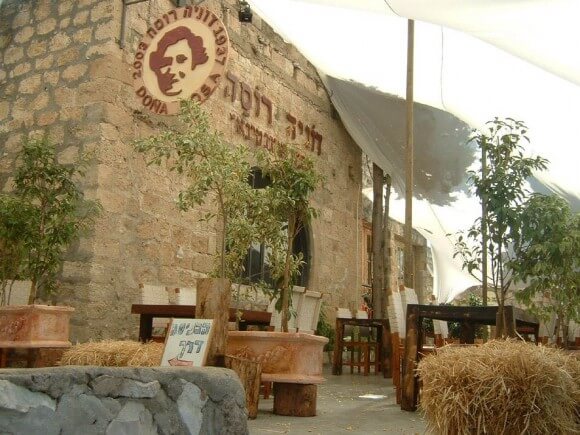

Thanks to Janco, the rustic stone homes that once belonged to Palestinians contain quaint artist studios and a large museum dedicated to his paintings. Janco drew his scenes of Arab life in typically Orientalist fashion, depicting the indigenous residents of the Galilee as a faceless, agrarian mass or as cartoonish stereotypes. The mosque that once served Ayn Hawd’s Muslim population has been converted into an airy bar called Bonanza, where Goldstar beer flows from the tap and pizza bakes in a woodburning oven. Visitors to the town are greeted at the entrance by Benjamin Levy’s The Modest Couple in a Sardine Can, a sculpture depicting a nude woman and a suited gentleman in a sardine can, which was unveiled at a ceremony led by President Peres in 2001.

Having survived the catastrophe of 1948, the al-Hija clan of Ayn Hawd set up a new village three kilometers away from what is today known as Eid Hod. They thus joined the eighty thousand Palestinians classified by Israel as “present absentees,” or refugees who had been permanently driven from their homes but not outside the borders of the country. In the decades that followed, the villagers resisted state attempts at removal. Unable to dislodge the al-Hija clan, the state surrounded them with a fence to prevent them from expanding their unrecognized village. In 2005, after decades of deliberate official neglect and a sustained campaign to highlight their plight, the residents of Ayn Hawd won official recognition—a stunning rarity for an unrecognized Arab village. For the first time, they were able to receive public services like trash removal and electricity.

I visited Ein Hod in June 2010. The village was charmingly quaint, and if I had not arrived with the intention of investigating its history, I might have felt welcome enough to spend a night or two at the local bed and breakfast. But Ein Hod’s residents had apparently been conditioned to treat the overly curious outsider poking around for details about the ghosts that still haunt them with extreme wariness. When I pulled out my video camera and began to ask the local artists about their studios, I was met with a mixture of suspicion and outright hostility. “I know what you’re doing!” a silver-haired woman sneered at me, insisting that I not film her.

Inside the Bonanza bar, I asked patrons if the place was in fact a converted mosque. “Yeah, but that’s how all of Israel is,” a talkative young woman from a nearby kibbutz told me as she sipped on a beer. “This whole country is built on top of Arab villages. So maybe it’s best to let bygones be bygones.”

Near a cluster of stone homes, I joined a group of aging Israeli tourists with waistpacks and big, floppy hats as a professional guide led them around Ein Hod. Speaking in Hebrew, the guide took them through the studios, informing them that they were inside “third generation houses,” deceiving them into believing that Israeli Jews were the original owners. While browsing the studios, I noticed that much of the art being produced was Judaica kitsch for sale to foreign tourists—generic shtetl scenes from the long lost world immortalized in Yiddish scribe Sholom Aleichem’s Tevye and His Daughters, a play that concluded with a tragic scene of Russians expelling the Jews from their shtetl.

Later, before taking her group to the town’s Hurdy Gurdy museum, a rustic workshop dedicated to the restoration and preservation of medieval European instruments, the guide mentioned a “welcoming committee” that vetted potential residents. This was apparently one device the residents of Ein Hod used to keep the Arabs down the road from returning home. Then there was the Absentee Property Law of 1950, which placed all “abandoned” Arab property in the hands of the JNF and the ILA, consolidating the state-sanctioned theft committed during the Nakba through democratically approved legislation.

During a break in the tour, the guide pulled me aside and demanded to know who I was. Introducing herself as Shuli Linda Yarkon, a PhD candidate at Tel Aviv University, the tour guide told me with great modesty that she was the leading authority on Ein Hod. She insisted that I allow her to review all the footage I planned to shoot, claiming that this would ensure that I not mistranslate words she used like kibbush, a Hebrew term that means “conquest” but is commonly used to refer to the occupation of Palestine.

“So what about the conquest you mentioned?” I asked her. “Why didn’t you tell the tourists who lived in the houses before 1948?” Visibly irritated, Yarkon resorted to the dreary vocabulary of post-structuralism to justify her revisionism. “I’ve concluded after years of research that there are really no facts when you discuss this issue,” she stated coldly. “There are only narratives.”

She assured me that Ein Hod’s Jewish population maintained excellent relations with the expelled residents: “Go ask them. They will tell you how they feel.” So I did. After following a winding dirt road around a hillside for several kilometers, I was inside Ayn Hawd, the Arab village. There was no installation art here, just a collection of mostly ramshackle houses, dirt roads, a mosque with a tall minaret, and crowds of scruffy kids playing in the streets. Almost immediately some of the town’s residents appeared from their homes to greet me. Among them was Abu Moein al-Hija, a village council member and schoolteacher who invited me to spend the rest of the afternoon with his family on a patio beside his home, which appeared newer and more stately than those of his neighbors.

Al-Hija told me his ancestors arrived in the village more than seven hundred years ago from what is now Iraq. Those members of his family who were expelled to Jenin in 1948 never returned home, even to visit. They told him they would be too angry to even lay eyes their former homes with the new Israeli occupants inside. When I mentioned the bar built into the old mosque, al-Hija shook his head in disgust. “It’s very bad. It’s an insult,” he said.

Al-Hija took me inside his home for a tour, showing me the spacious, immaculately clean parlor and the picture window with a sweeping view of the valley below. He had built the whole place, he said with pride. Down a hall, his thirteen-year-old daughter, Ansam, was reclining on the floor of her room reading John Knowles’s novel of American prep school boys, A Separate Peace. She leapt to attention when I entered and spent the next ten minutes showing me her library.

With night setting in, Moein and his family took me back on the patio. There, he unfurled the map of Mandate-era Palestine that so many Palestinian families I have visited kept in their homes. It was maps like these, which highlighted the hundreds of towns disappeared by the State of Israel, that Uri Avnery called “more dangerous than any bomb.” Al-Hija ran his fingers over the names of scores of villages destroyed on the coast between Jaffa and Haifa by Zionist forces in 1948, pointing to Kafr Saba, Qaqun, al-Tira, and Tantura, the site of a massacre of unarmed Palestinian prisoners on the beach just one month after the Deir Yassin massacre. Moein was a history teacher, but the state had forbidden him from discussing these events in his classroom and was in the process of criminalizing their public observance.

As darkness blanketed the hills, I realized that I had lost track of time. I told al-Hija that I needed to get back to Tel Aviv. With that, his wife rushed into the house and gathered a bunch of grapes she had picked from a tree in the family’s garden, handing them over to me in a Tupperware bowl. On the drive down the coast, as I breezed by the dunes and sandy flats where the heart of Palestine once pulsed with life, I thought of a quote by the seventeenth-century Jewish mystic Baal Shem Tov inscribed on a wall at Yad Vashem, the Israeli Holocaust memorial museum. “Forgetfulness leads to exile,” it read, “while remembrance is the secret of redemption.”

In his 1963 short fiction story “Facing the Forests,” the Israeli author A. B. Yehoshua portrayed a mute Palestinian forest watchman taking revenge by burning down a JNF forest to reveal the hidden ruins of his former village. Imagining that the fictional tale had come to life, right-wing Israelis began demanding a search for the Arab who must have sparked the blaze on the Carmel Mountains, which the Israeli police described as a deliberate act. While Yedioth Ahronoth blared without evidence, “Hezbollah Overjoyed by Fire,” Michael Ben-Ari, an extremist member of Knesset from the National Union Party, called for “the whole Shin Bet” to be mobilized to investigate what the settler media outlet Arutz Sheva said “may turn out to be the worst terror attack in Israel’s history.” After the damage was done, an official investigation determined the fire to be the result of simple negligence.

From the Book: GOLIATH: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel by Max Blumenthal. Excerpted by arrangement with Nation Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2013.

The fact that they planted trees to cover up their crimes is both a confession and a demonstration of their absolute depravity.

“The mosque from the Palestinian village of Ayn Hawd, which is now a bar in the Israeli village of Eid Hod.”

And some zio posters here wonder why the Palestinians are hesitant to “share” al Haram ash Sharif and to permit Jewish worship…

A super great story by Max that covers a whole lot of issues.

The destroyed village of Imwas that was in the Latrun that Max talks about is the Emmaus mentioned in the Christian Bible where the resurrected Jesus met and had supper with 2 of his deciples.

Superb.

Hey Max,

Do you have any solutions? Or just insipid arguments about how the Israelis are the only ones in the history of humanity to live where other cultures lived before them and how Israelis are all awful people while every Arab is a fantastic person who gives you grapes and invites you into their homes?

It’s exactly as your tour guide said – there are no facts in these places, only narratives. And you’ve adopted one of them wholesale.

Yishai mobilised his base when he said that criticism of his ineptitude as minister (no firefighting helicopters as they only work with white phosphorous) was driven by hatred of the sephardim. Zionists never did responsibility.