This review of Max Blumenthal’s book Goliath appeared in longer form at Jerome Slater’s site. He gave us permission to excerpt. –Ed.

This review of Max Blumenthal’s book Goliath appeared in longer form at Jerome Slater’s site. He gave us permission to excerpt. –Ed.

In my own work on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, I start from two premises. The first is that in light of Israeli intransigence, there is no chance of attaining a two-state settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict without strong and sustained pressures from the American government, very probably including making its military, economic, and diplomatic support of Israel conditional upon the end of the Israeli occupation and repression of the Palestinians and the creation of a viable and genuinely independent Palestinian state.

The second premise, however, is that there is no chance of these essential changes in U.S. policies occurring unless a majority of American Jews become convinced that such actions are required by Israel’s own best interests—indeed, without exaggeration, required in order to save Israel from itself, and not only in its relations with the Palestinians but in its domestic political and societal health as well. Of course, it would be far better if Jewish support for American pressures on Israel were motivated at least as much by moral anger at Israel’s behavior and sympathy for the Palestinians; but, sadly, except for a small minority of the American Jewish community, that is not going to happen.

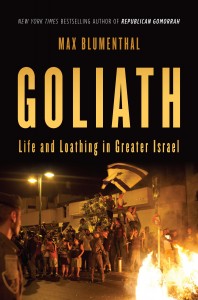

Given those two premises, I have mixed feelings about Max Blumenthal’s new work, Goliath: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel–“the result of over four years of on-the-ground research and reporting,” as Blumenthal writes in his preface. On the one hand, it is a powerful and impressive work by one of America’s most astute and courageous young journalists, a highly detailed and vividly written compendium of Israel’s criminal—no other word will do—occupation and repression of the Palestinian people. In persuasive detail, Blumenthal reviews and exposes not only the criminal behavior of Israel towards the Palestinians, but also the variety of ways in which Israel is becoming increasingly rightwing, anti-democratic, and even “fascistic” (a term increasingly used by Israel’s own dissenters)—in its schools, in its courts, in its racism (against both the Palestinians and African refugees in Israel), in its police repression, and in its growing restrictions against free speech and protest by Jewish Israelis, let alone by its own Palestinian citizens.

Blumenthal quotes Akiva Eldar, one of Israel’s greatest journalists, who sums up the findings of Israeli public opinion surveys: “Israeli Jews’ consciousness is characterized by a sense of victimization, a siege mentality, blind patriotism, belligerence, self-righteousness, dehumanization of the Palestinians, and insensitivity to their suffering.” As even Eric Alterman’s blast at Goliath in Nation (one of the few reviews in the mainstream media) concedes, the book is “mostly technically accurate”—an absurdly backhanded way of admitting that he can’t challenge the detailed evidence laid out by Blumenthal. In a rational world, then, Goliath should convince the American Jewish community as well as non-Jewish “pro-Israelis” to support the necessary changes in US policies in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

It won’t, however—primarily because so many Jewish and other American “pro-Israelis,” like Alterman, are impervious to the facts. But Blumenthal must also bear at least some share of the responsibility for the hostile reception that Goliath is receiving—even from “liberal Zionists,” let alone from the majority of Israelis and American Jews who are well to the right of that small and increasingly beleaguered group.

The first problem concerns the disjuncture between the audience that Blumenthal wants to reach and his strategy for doing so. It is clear that Blumenthal agrees with the two premises I describe above, for in his preface he writes: “it is Americans’ tax dollars and political support that are crucial in sustaining the present state of affairs. I want to show what they are paying for, the facts as they really are today, in unadorned and unsanitized form, without sentimentality or nostalgia….Readers may not agree with all of my conclusions, but I hope they will carefully consider the facts that appear on these pages. They are, after all, the facts on the ground.”

However, Goliath is not likely to succeed in terms of its own purpose. For those who already have some knowledge of, and are increasingly disturbed by, the realities of Israeli policies and the U.S. collaboration with them, Blumenthal’s detailed reporting, analyses, and conclusions will be entirely convincing. But since that is still a small minority of American Jewish community, the problem is that Goliath is likely to end up as merely preaching to the choir. To be sure, that is far from pinning most of the responsibility for such an outcome simply on problems within Blumenthal’s book: the right wing in Israel and the U.S., Jewish or not, can’t be convinced by any evidence, period. The only hope, then, are Israeli and American centrists, who are unaware of the full truth but who are open, in principle, to reconsidering their position when the facts—powerfully presented by Goliath—are overwhelming and irrefutable.

For several reasons, however, Goliath is not likely to have much of an impact on the mainstream centrists in America, the most importance audience for any work seeking changes in the status quo. Given Blumenthal’s overall argument, however justified by the facts and evidence he presents, reaching that mainstream would have been an uphill battle in any case. However, Blumenthal has made the hurdles even greater because of the general tone of his writing and the loaded language and even outright contempt that he occasionally indulges in—mostly not without good reason, I should add, but a serious mistake nonetheless.

The Chapter Headings

The problems begin with a number of Goliath’s sardonic chapter headings, which are designed to dramatize the vast gaps between how the Israelis see themselves–especially in their relations with the Palestinians as well as in their own highly flawed democracy– and the realities. Among other provocative titles are “The Silence of the Lambs,” “Riding the Ass,” “The Best Times of Their Lives,” and “A Wet Dream.” Far more unfortunate are those that are intended to compare Israeli behavior to that of Nazi Germany: “The Concentration Camp,” “The Night of the Broken Glass,” and probably even “How to Kill Goyim and Influence People.”

In response to critics put off by such in-your-face headings, Blumenthal has defended himself by arguing that the facts justify the title headings. In the chapters dealing with the gap between Israeli perceptions and the realities, he indeed has a very good case that they do; nonetheless, in my judgment they are still a tactical error. The implicit or explicit comparisons between Israeli and Nazi behavior are especially unwise. That is not to deny that there are indeed a number of Israeli actions that are likely to call to mind Nazi behavior, especially in its crushing of resistance in the occupied territories. Nonetheless, they are very likely to be counterproductive in their effects on the intended audience for the book—which, to repeat, is not, or at least shouldn’t be, the far left in the Jewish communities in the U.S. and Israel, which already has noticed the parallels.

Further, even on the merits, and even given some basis in actual Israeli behavior, a fair treatment would have to call attention to what are still vast differences—to put it mildly!–between that behavior and that of Nazi Germany. Better, then, to just set out the facts, and let the readers think of the implications on their own. Or, alternatively, follow the strategy that I have sometimes employed: note the comparisons with the Israeli responses to Palestinian uprisings and, say, the Soviet crushing of the Hungarian and Czech revolutions –anything, that is, but Nazi Germany.

Language and Tone.

In addition to a number of the chapter titles, in too many places Blumenthal allows himself to indulge in loaded language, in some cases unfair on the merits and in others not without reason but nonetheless unnecessarily inflammatory. Here are some examples:

*The Israeli state has “corralled” the Russian immigrants “into the Zionist project, using them as human fodder to fill the ranks of the army and the major settlement blocs.” (22; all page numbers are from the Kindle edition of Goliath)

*When the managing editor of Time Magazine went to Israel in May 2012 to interview Netanyahu, he is described as “eager to relay a heavy dose of Bibi-think to the American public.” (29).

* Michael Oren, the Israeli Ambassador to the United States during most of Netanyahu’s current term is described as Netanyahu’s “attack dog,” to be “sicced” on critics of Israel. (29) To be sure, Oren is dreadful, but the language is off-putting.

*Blumenthal observes that a former three-hundred-year-old Palestinian mosque in Jaffa has been turned into an S & M night club. Fair enough, and sufficiently devastating without further comment—but what purpose is served, other than sheer contempt, when Blumenthal adds that “male bondage enthusiasts enjoyed having the remainder of their circumcised foreskin sewn over the tip of their penis?” (46-7)

*In shops beneath Blumenthal’s flat, “Gun-toting Orthodox settlers” and soldiers are not merely eating, but are “gorging themselves.” (237)

*It is sufficient to describe the Israeli army repression in the occupied territories without calling it the “jackboot” of repression (378), a term which is widely associated with the German army in its repression of the resistance in Nazi-occupied Europe.

The Rejection of Zionism

Blumenthal’s attack on Zionism, even—or especially–liberal Zionism, is an even more important reason why Goliath is almost surely not going to cause the majority of American Jews and other “pro-Israeli” groups to change their minds and support serious U.S. pressures on Israel.

There is a strong case for distinguishing between Zionism’s argument for the continuation of Israel as a Jewish state today (as opposed to a state of all its citizens) from the earlier Zionist arguments for the creation of a Jewish state in the aftermath of the murderous Russian and East European anti-Semitism of the late 19th / early 20 centuries and, obviously, the Holocaust. However, Blumenthal strongly implies that Zionism has always been wrong.

Early Zionism. Throughout the book Blumenthal describes Israel, from its outset, in terms of colonialism. For example, he writes: “In the narrative of the new nostalgia, Israel’s crisis began in 1967 with its conquest of new Arab land, and not in 1948, when it defined its settler-colonial character.” (272) Elsewhere, Israel is described as a colonial power, or one that has a “colonial character.” Or, he argues, kibbutzim that were established—“planted” is his term–in the Galilee or along Israel’s borders with Gaza were part of the “colonial agenda” designed to “to hold back the restive natives” on the other side. (87)

It cannot be denied that there are some legitimate comparisons between Western colonialism and Israeli behavior–unquestionably of its ongoing occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and Jerusalem since 1967, but even in the pre- and early post-state period. The parallels are obvious, and Blumenthal is hardly the first Jewish or Israeli dissident to point to them—yet, there are also highly important differences, and it is incumbent upon critics of Israel to acknowledge them in a serious manner.

It is beyond the purview of this review essay to go into detail, but at least at the level of motivation (consequences are a different matter), anyone describing Israel in terms of colonialism must also acknowledge that the driving force behind early Zionism was the felt urgent necessity (I would say, objective urgent necessity) to create a haven from murderous anti-Semitism. That must be distinguished from the obvious motives and complete lack of objective necessity that drove Western colonialism– power for its own sake, economic gain or simple greed, or “the white man’s burden,” none of which had the slightest thing to do with early Zionism….

Zionism Today

In one of the most important—and revealing—passages in Goliath, Blumenthal further discusses his interview with David Grossman:

For Grossman and liberal Zionists like him, the transformation of Israel from an ethnically exclusive Jewish state into a multiethnic democracy was not an option. “‘For two thousand years,” Grossman told me when I asked why he believed the preservation of Zionism was necessary, “we have been kept out, we have been excluded. And so for our whole history we were outsiders. Because of Zionism, we finally have the chance to be insiders.” I told Grossman that my father had been a kind of insider. He had served as a senior aide to Bill Clinton, the president of the United States…working alongside other proud Jews like Rahm Emanuel and Sandy Berger. I told him that I was a kind of insider, and that my ambitions had never been obstructed by anti-Semitism. “Honestly, I have a hard time taking this kind of justification seriously,” I told him. “I mean, Jews are enjoying a golden age in the United States.”’(275)

Blumenthal then adds: “It was here that Grossman, the quintessential man of words, found himself at a loss,” the apparent implication being that his (Blumenthal’s) argument is unanswerable.

It isn’t. His argument is common among Jewish post- or even anti-Zionists: the core Zionist principle, the need for Jews to have a state of their own, is said to be now anachronistic because of the strength of Jewry and its “insider” status in the United States. For three reasons, it is not a persuasive argument. First, it is ahistorical, even in terms of the United States. In my own lifetime there was considerable anti-Semitism in the 1930s and early 1940s—not exactly ancient history. In this connection, three recent major works that include discussions of anti-Semitism in America before WWI–especially prominent in much of the isolationist movement– make instructive reading: Susan Dunn’s 1940; FDR, Willkie, Lindbergh, Hitler (2013), Lynne Olson’s Those Angry Days (2013), and Philip Roth’s exercise in alternate history, The Plot Against America (2004), which persuasively imagines what might have happened in America if Charles Lindbergh had become president, an altogether realistic possibility in the late 1930s.

In any case, secondly, I am aware of no supporter of Zionism who focuses on the Jewish situation in the United States in support of the argument that Israel must continue as a largely-Jewish state as a potential refuge against the rise of anti-Semitism. It isn’t ancient and therefore irrelevant history that in late 19th and early 20th century European anti-Semitism was not only severe but murderous—in Czarist Russia, in eastern Europe and, of course, in Germany, where the Jews were increasingly assimilated and powerful– until, that is, the rise of Nazism. And even when contemporary anti-Semitism has fallen short of becoming murderous, it was sufficiently severe to convince over a million Russian Jews that it was wise to emigrate to Israel.

Third, and most importantly, there is no prospect that Israel will agree to a peace settlement that doesn’t preserve Israel as a Jewish state. That fact of life alone makes the post-Zionist argument irrelevant, even if it were a persuasive one. Even a two-state settlement that preserves Israel as a Jewish state is becoming increasingly remote, let alone the transformation of Israel into a single binational state in which the Jews would almost certainly become a minority in the next few decades.

Conclusion

What is the best strategy to try to persuade Americans, especially Jewish Americans, that their nearly unconditional support of Israel is contributing to the current disaster? My argument on this issue assumes that the American Jewish community and other pro-Israeli groups are divided into three groups. The first are ideologues who are uninterested in the facts and can’t be moved. The second is a probably smaller group who not only know but care deeply about the facts, and need no further convincing that the unconditional US support of Israel is both morally wrong and contrary to the true interests of both Israel and the United States. The third and probably largest sector are the “liberal Zionists”: American Jews (and their supporters) who are proudly liberal in their general values and in the context of American politics, who are unhappy about the Israeli occupation, oppose the settlements, and support a two-state settlement—but who are not prepared to say either that Zionism was a mistake from the outset or even that it is no longer justified.

Because of problems in both tone and—less often—substance, Goliath will probably not have much of an impact on these liberal Zionists (sometimes more unkindly described as “PEPS,” Progressives Except for Palestine). Indeed, most of them will never even hear about Goliath, let alone read it, because Blumenthal’s frequently confrontational or sardonic rhetoric has apparently resulted in a decision by the mainstream media to ignore the book.

That is most unfortunate, for Blumenthal is right that Israel’s behavior towards the Palestinians is indefensible and antithetical to what we used to be pleased to call “Jewish values.” Thus, I fully understand why he has chosen to bluntly express his (mostly) justifiable rage and contempt–to let it all hang out. Indeed, I’ve sometimes succumbed to the same temptation—but almost always to my later regret. Better, in short, to just let the brute and irrefutable facts speak for themselves.

To be sure, as one of Goliath’s best chapter titles puts it, for many Israelis and their US supporters “There Are No Facts.” Even so, those of us who share Blumenthal’s values and his knowledge of the realities have little choice but to continue our work and hope that at some point the facts will actually come to matter.

This 3-part defense of Zionism is poor.

1. Blumenthal is right that Jews are no longer outsiders in western nations, but the need for protection from racist persecution cannot justify Zionism even if this were not the case. Jewish privilege in Israel can only cause more of this sort of injustice, it just targets Arabs (and others) instead of Jews. Only multiculturalism and equality can protect minorities and end ethnic strife.

2. The ‘recent’ exodus of Jews from the former USSR does not demonstrate that there is a need for Zionism. All western democracies accept Jewish immigrants and refugees, and a multicultural Israel would also welcome them. There is no need to have a state that automatically extends citizenship to anyone based on ethnicity.

3. That Israel doesn’t look willing to ever abandon Zionism is not in itself an argument for Zionism. It didn’t look possible for South Africa to choose to mend its ways long before it did. Injustice is inherently unstable, and Zionism WILL end. I just hope it will end peacefully.

I’m not sure if Prof. Slater will respond to the comments and questions here but if so, I have a few:

1. You say:

Did early Zionism propose a binational State or a federation? Did early Zionism believe in coexistence with the indigenous Palestinian Arabs?

How long did this early Zionism exist IF your answer is an affirmative for the questions I listed above?

2. You take issue with several chapter titles and other cases of ‘loaded language’.

Max is often referring to what Israeli politicians say themselves. Or what Israelis say themselves.

For instance, “night of broken glass” probably refers to the price-tag violence and ‘pogroms’ against Palestinians:

You seem to think this ‘language’ will hurt the feelings of that oh-so-valuable ‘centrist’ demographic. Who are these centrists who are so incompetent they can’t do a quick Google search to SEE FOR THEMSELVES that Israeli politicians characterize these ‘pogroms’ as POGROMS?

3. You conclude by saying

What difference does it make whether Max is sardonic or not?

We have see the organized American Jewish community boycott Palestinian children’s ART exhibits.

There are so many examples of a crazy UNHINGED response by the organized American Jewish community to criticism of Israel and promotion of Palestinian agency. Too many to list.

I see no point in placating this audience.

Aren’t there plenty of journalists and scholars who report on this conflict in an antiseptic manner?

Chomsky!? And he gets called an antisemite as well.

I think the problem isn’t Max’s language. It’s you Prof. Slater. Your selective memory as if Max Blumenthal is the first person to criticize Israel.

You intentionally forget the track record and the many other criticisms of Israel. You think those other critics weren’t ignored or marginalized or slammed as antisemitic? You think Max is the first and only?

Absurd. I think you just don’t like the feelings this book evokes. Why shouldn’t you? You are a ‘liberal’ Zionist.

Enough. Putting aside for the moment the opening phrasing about two states – no, I won’t put that aside. Starting with this two states piffle is enough to walk this essay into its own demise. Can people stop blithering about “pre-1967 borders?” There weren’t pre-1967 borders because Israeli administration has never acknowledged *any* borders. It was a problem before 1967 and it’s been the same problem since. When Uri Avnery talks like this, it’s annoying but not blithering, because what he describes as a solution is within the zone of “one state” even if he doesn’t like the term. But the more familiar, all-too-nuanced falsity used by Dr. Slater was idiocy from the start.

The more so when any, and I mean any at all, authority for solutions is granted either to the Israeli government or to Jewish Americans. Neither has any. Dr. Slater, consider that carefully. Drive it into your brain.

1. “But the Israelis would never agree” is not the issue – I don’t care. Do you? Does anyone? This is not about leading privileged and vicious people to agree, it’s about exerting force effectively to achieve justice. Sound abstract to you? It’s not. Raw sewage flooding Gaza is not abstract, nor is stopping it. The Israeli establishment isn’t going to agree to stop it – so now you look mournful and helpless.

2. “But Jewish Americans don’t unanimously agree” is not the issue. This is related to a long-standing toxic Cold War assumption, that people living in the U.S. who feel some affinity to Place X get to exert U.S. policy authority toward it. That policy dates back to British policy concerning expatriates, using them as agents for regime change, which always, always blew up in their faces, and yet which remains at the core of CIA and State Dept culture. It’s at the heart of our absurd policy toward Cuba, and no surprise, it tends to turn people in this position into rabid interventionists and militarists, which then feeds back into the policy as “see, see, if they hate the regime so much, they must be sincere and correct.” This already ridiculous notion goes bull-goose-loony absurd when applied to Jewish Americans, relying as it does on false nativism for the European emigrants to Palestine and later Israel, and on false identification of Judaism with Israel as a state.

Again: arriving at justice in this part of the world has nothing to do with compliance on the part of those in power in Israel, not in the past, and not now. Nor does it have anything to do with Jewish Americans considered as a political unit, both in principle and also because no such unit exists. (The problem with Jewish opinion in America is not that there is a single one, but rather that powerful individuals and groups, Jewish and non-Jewish, act as if there is.) The only valid response to someone who appeals to either is, “I do not care.”

Dr. Slater, you are trapped in motifs that are historically real, but were wrong historically and continue to be wrong now. Discrimination against Jewish Americans was real – transferring resistance to it into second-order patriotism for Israel was and is wrong. The U.S.-Soviet accord to get Israel into the UN as quickly as possible was real – overlooking the Israeli government’s arrant disregard for the conditions pending its acceptance by the United Nations – still disregarded! – was and is wrong.

And then there are the ones which were historically ridiculous as well, such as confounding blatant bribes and promises of privileges for Russians with refuge for victims of oppression, or as I observe constantly, confounding establishing the Israeli state with anything to do with Holocaust survivors.

Max Blumenthal quite rightly did not write his books to convince Israelis or pro-Israel Jewish Americans of anything. He wrote it for anyone and everyone who cares about justice. If some Israelis and some pro-Israeli Jewish Americans are affected positively by it, then so much the better – but that is neither sufficient nor necessary toward the ends.

JS: “It is beyond the purview of this review essay to go into detail, but at least at the level of motivation (consequences are a different matter), anyone describing Israel in terms of colonialism must also acknowledge that the driving force behind early Zionism was the felt urgent necessity (I would say, objective urgent necessity) to create a haven from murderous anti-Semitism. That must be distinguished from the obvious motives and complete lack of objective necessity that drove Western colonialism– power for its own sake”.

What Slater is saying is that we must consider “ends” rather than only considering “means”. Israel’s colonialism is not, he says, the same as other colonizers’. Perhaps so. But so what? Israelis who can are now moving tio Germany, to the USA, etc. This means that [1] they are free to go places, [2] they want to go places, [3] they do not regard the world as a dangerous place for Jews, [4] they prefer other places to Israel. Given this (admittedly small) exodus of Israeli-Jews from Israel, why are Israel’s “ends” and “means” still unchanged — or perhaps intensified?

People often ask whether particular “ends” justify particular (illicit) “means”.

There is much evidence that the Zionist surge (1930s, especially 1945-48) well understood that the Palestinian Jews would need to grab a lot of land not already owned by them and expel a lot of people (Palestinian Arabs). They knew these things and planned for them. The need to do this was not a surprise to the leadership. It was part of their plan. they desired to create “a land without people” to fill with Jewish immigrants.

So, the Zionist surge — while it had “ends” in mind — had “means” also clearly in mind.

And the fact that today’s Zionism continues to usurp land and to oppress (and even expatriate) Palestinian Arab people shows that the “means” were not EVER rejected, not EVER regarded as temporary. Israel has never said it is sorry. Israel has never offered to give any of the land seized back, to allow any of the expelled people back.

Slater’s demand that we look at Zionism’s “ends” (rather than only at its “means”) is particularly hard for me to credit given that in the USA Israel and Zionism are so THOROUGHLY KNOWN as philanthropic and so very, very LITTLE KNOWN as criminal. “Goliath” sets out to provide a fact-book for establishing some of the “criminal” part of the means/ends dichotomy.

How, one wonders, are Americans to learn the “means” part of Israel’s “ends” and “means” if no-one publishes them?

As indispensable as Jerome Slater and other liberal Zionists have been for the freedom movement in Palestine, they undermine that movement when they frame it as a territorial dispute rather than a struggle for equal human rights in all of Palestine. The utmost of his ambition is to “cause the majority of American Jews and other ‘pro-Israeli’ groups to change their minds and support serious U.S. pressures on Israel.” He urges a more nuanced understanding of Zionism, but it’s an understanding that clashes with the unremitting reality on the ground–Goliath’s depiction of which, he agrees, is “mostly technically accurate.” Liberal Zionists’ kinder, gentler brand of Jewish ethnocracy has no hope of mobilizing a global movement comparable to the one against South African Apartheid. Equal rights for all the people of Palestine, Jew and non-Jew alike, does. And despite Slater’s assertion to the contrary, there is even hope that many “centrist” American Jews, increasingly divorced from Zionist Israel as a keystone of Jewish culture, will join the equal rights movement.