Unarguably, one of the most notable achievements of Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress was that they were able to dismantle the apartheid structure of law in South Africa without the destruction of the colonial population. Though their dominance of the political system has ended, the white community, both British and Afrikaner, remains firmly ensconced within the cultural and economic life of the nation. It is hard to overstate how unusual this is.

During the course of the Decolonization movement, there were two other African countries that faced the problems of South Africa–democratic rule by a minority population of European settlers. Neither of those situations ended well. In Algeria, when the FLN achieved victory in 1962 and the French government agreed to independence, the entire community of French Algerians, many of whom had roots going back 130 years, departed en masse, destroying their infrastructure behind them. In Zimbabwe/Rhodesia, the 1979 agreement that ended the civil war and led to the fall of the Rhodesian apartheid government included provisions for the protection of the white minority. But by 1999, all but a handful of these citizens had fled. The question must be asked, why was South Africa so much more successful in its rapprochement than its contemporaries? Even more that than, why was rapprochement even a possibility?

I said earlier that there were there were two other countries facing the same problem as South Africa. In fact, there were three. The last one is Israel, which enjoys democratic governance by its Jewish population, while millions of Palestinians in the West Bank have spent 46 years under military occupation, watching as their land is steadily confiscated for the use of Israeli settlers. Right now, most people see the Israel-Palestine conflict as an ethnic one. Even people with sympathy for the Palestinian position all too often dismiss the whole situation by lamenting the fact that the two groups “just hate each other so much”. This is because, for all intents and purposes, it has been an ethnic conflict. The Palestinians have used the weapons of terrorism, of insurgency, of popular insurrection, all aimed at Israel (and often the Jewish people) in general. It has been, for all intents and purposes, a war fought between two ethnic groups. This has contributed greatly to the international perception that the whole thing is just an unsolvable mess. But this is starting to change. The Palestinian Civil Society call for a Boycotts, Divestment, and Sanctions campaign against Israel utilizes the language of international justice and human rights. It calls for specific changes in Israeli policy and governance, and it does so on the basis of specific, quantifiable actions taken against the Palestinian people in violation of international law and basic human rights. In effect, it transforms the conflict from a war to the death like Algeria or Zimbabwe/Rhodesia, and into South Africa-style campaign to bring about the end of a government dedicated to racial dominance.

Some people may wonder, does it really matter the manner in which the struggle against Israeli oppression is fought? After all, all three of those countries did eventually gain victory. And to be honest, I agree. If the BDS movement collapsed tomorrow, Palestinian resistance would continue. And I believe it would eventually succeed. But let’s be clear. If the BDs movement collapsed tomorrow, the struggle would almost certainly return to the methods of violent insurrection and terrorism. And if and when they achieved victory, the results would look far too similar to the post-independence chaos and bloodshed of Algeria or Zimbabwe for comfort. This is why we must support BDS. Building a Palestinan freedom campaign built on the precepts on justice, human rights, and international coordination is the only way to ensure that when the Israeli Apartheid regime falls, what emerges truly will be a democracy of all its citizens, and not the ascendency of the blood-stained and vengeful victorious opposition.

Just look the past year, many artists, companies boycotted this regime. BDS works. Finkelstein should recognize.

BDS can motivate countries — the people and the national governments — to take action of a SANCTIONING nature.

Trade sanctions against Israel have begun. some UK supermarkets refuse Israeli produce. Dutch Pension funds took their money out of Israeli banks.

One hopes that all this will increase into a cascade. It does not need to be 100%. It only needs to hurt enough Israeli trade enough for the Israeli business community to tell the government to “shape up”. That is the purpose of BDS — in my opinion.

My hope is that BDS wil become sufficiently wide-spread before its effects cause close dowen of the settlements, that the countries practicing BDS will CONTINUE — thereby giving a possibility of solving the other two problems (after settlement eradication) — democracy/non-discrimination within Israel and PRoR for the exiles of 1948.

The danger (in the event of success) is that the momentum will dry up after the initial success that the secondary goals will not be met.

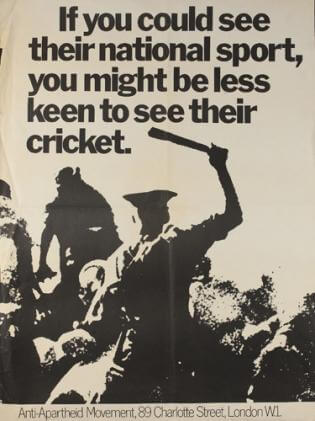

Those ads are anti-afrikaner.

Why single out South Africa when there are plenty of human rights violators around the world?

South Africa is surrounded by a bunch of hostile countries.

This issue is too complex for the boycotters to understand.

Peace will come when the ANC recognizes the right to exist of White South Africa.

Nathan,

I appreciate your article, your insights, and how you see the struggles as similar and their methods as both possible.

I disagree with juxtaposing the two struggles and their methods, however.

A struggle for human rights can also be a struggle for a group’s liberation. If the group is liberated it can protect their rights, and vice verse.

BDS is not necessarily different from resistance either. Much of the intifada for freedom was civil disobedience, failing to pay taxes, etc. Without any violence it still would have been resistance for freedom. There is also, by the way, an Arab boycott of the State, in existence for a very long time. It’s distinguishable from BDS, because the latter is home grown. However nonetheless the tactic was the same, even if BDS is more limited to the issue of settlements. This is why neither the tactics nor the goals nor the framework of resistance (a group’s liberation vs. human rights) are in contrast to eachother.

However, I could see supporters of the State’s system as declaring they are very different and that they support one over the other. Namely, the supporter of the system could say he agrees with the subject people’s human rights, but does not want a liberation where they all return to their homeland- as if the two ideas were so vastly different.

I also see a wide range of tactics- on one hand JStreet’s tactic of talking to the governments in the US and Israel and thinking it is a matter of rhetorical persuasion alone, for the system to see that the survival in the long term political arrangement is best served by ending occupation of some territories. This of course is a failed tactic when taken alone because the state has major material interests in settlements. This is why the State has been so aggressive.

On the complete opposite hand there is a tactic of promoting some kind of invasion, which practically nobody supports anyway.

Thus a supporter of the state can claim they want one tactic and not the other. In reality however, no tactics are in complete contradiction as to their goal (as if one tactic went with one goal only- rights vs. freedom)- even though of course not all tactics are wise.

Thank you for this thought-provoking analysis. I’d be interested to read comments from people who are more knowledgeable than me about Algeria and Zimbabwe.