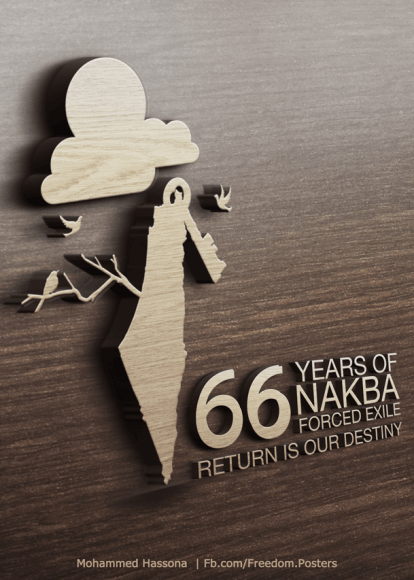

May 15 marks the 66th anniversary of al-Nakba or “The Catastrophe,” the day that led to the systematic dispossession of two-thirds of the Palestinian population — exiled from their homes, bereft of their property, land, and dignity. This day, with the creation of the state of Israel, came the creation of the Palestinian refugee crisis. The creation of a nation on the land of another nation, with people forcibly removed from their villages — villages that would be expunged from the map, but not from the memories of those who inhabited them.

According to the Institute for Middle East Understanding, as of 2008, more than 4 million Palestinian refugees were registered with the United Nations, and at least another estimated 1 million were not registered. Thus a majority of the Palestinian people, around 10 million persons, are refugees.

These refugees remain outside of a home that they are not allowed to return to — a home many have never known.

The Nakba presents the ultimate paradox: the attempted erasure of one history, one heritage, one narrative, and the fabrication, manipulation and misrepresentation of another. The creation of the state of Israel was intended to provide a safe haven to a persecuted and oppressed population, at the expense of perpetuating that same vicious and unjust cycle against another. Cruel, cruel irony.

I didn’t live through the Nakba. I’ve never even been to the village my father and grandparents were born in. But I am Palestinian, and its repercussions reverberate throughout my existence. The Nakba has left me scarred and shattered, but still resilient and hopeful.

The Nakba means my identity remains fragmented. My homeland is deemed illegitimate and nonexistent by politicians and pundits who couldn’t locate it on a map. I’m a mess of qualifying phrases and unexplainable questions; technicalities and incomprehensible resolutions. My life is defined by borders and accords, checkpoints and closed crossings, passports I’ll never have and ID cards I don’t know if I want. West Bank. Occupied Territories. Gaza Strip. 1948. These demarcations define me without my will and confine me without my consent.

The Nakba means my husband and I may never be able to visit the village my family is from because he was born in Gaza, and is therefore forbidden entry to any other part of Palestine.

The Nakba means my children don’t have Palestinian parents; they have a mother whose family is from the West Bank and a father who is from the Gaza Strip — two parts of their heritage isolated from one another, two worlds that can not meet or intermingle. Apartheid.

The Nakba means the validity of my identity will be questioned. Society scrutinizes the accuracy of the arguments I make, assumes the bias of opinions I hold, attacks the humanity my people aren’t allowed to possess.

No, I haven’t suffered physically because of the Nakba. My suffering has been an existential one. Where do I belong? How do I understand a place I’ve scarcely ever been? How do I identify with a heritage I celebrate and attempt to preserve in spite of a sustained effort to obliterate and appropriate it? What is the extent of my resistance to an oppressive force I don’t live under? Will I ever be capable of contributing anything of meaning to this cause? How will this impact my children and will they care to maintain this struggle?

As we commemorate yet another anniversary of the Nakba while Palestine remains under occupation, I am optimistic that 66 years later, I am inspired by this land. I am hopeful that the legions of students who have reinvigorated this cause on campuses nationwide will ensure that Palestine is on the agenda of those striving for social justice. I am proud that so many young boys and girls rush to learn traditional dabka and exhibit their culture with confidence. I envision a future when criticism of Israeli apartheid is no longer equated with anti-Semitism, but understood to be a position taken by all those who seek justice.

The Nakba has equipped me with an emboldened spirit passed down through generations of Palestinians scattered across the globe — a spirit spread far and wide, split and fractured, born of catastrophe, but bound to be gathered back in one land, one people destined to triumph over a painful past.

This post originally appeared on the website Sixteen Minutes to Palestine.

I don’t want to let your moving words go without comment, but it’s hard to know what to say beyond expression of sympathy and of respect. I don’t altogether think it paradoxical that people should try to obliterate traces and memories of those they have wronged. It’s logical enough to try to make the Palestinians seem inauthentic, even grotesque, in their claim to Palestine and then to proceed to make them inauthentic (abnormal in their customs, hostile and unforgiving) in the West also, strangers everywhere. Such were the Jews once. It’s a terrible trap. Do you fight back and try to regain authenticity by saying ‘We are as normal a part of the Western world as anyone’ or does this destroy your sense of being Palestinian?