I don’t want to mix politics with sport. Really, I don’t. Because I’m not intellectually comatose, though, I have no choice. Those who control the narratives of competition are at fault. They invest the proceedings with flags, anthems, fighter jets, and feel-good stories about white saviors of black athletes and of inner-city youth who need only reach for those bootstraps in order to enjoy the bounties of American meritocracy.

Then there are the publicly-funded palaces, which often replace relatively young stadiums that no longer contain the requisite luxury suites to maximize an owner’s profit. This form of politics is less visible than the jingoistic circus that accompanies live broadcasts, but it informs broader issues of taxpayer abuse and gentrification. Wealthy franchise owners raid the public treasury for their private use, a form of welfare incalculably worse than that associated with the illusory black women of Reagan’s manic imagination.

Republicans are free marketers for the poor, but socialists for the affluent.

The talking heads insist that politics and sport should be separate. They really mean to say that politics incompatible with nationalistic clichés have no place in the timeworn metaphors of competition.

It’s more difficult to sequester politics from competitions like the World Cup, where national conflict is often part of the athletic tension. As the great tournament approaches, we’ll be treated to plenty of third-rate geopolitical commentary, but international discord is not the most relevant form of politics at play. You’ll hear little about it in corporate media, but the handling of the tournament itself, as with nearly all global sporting events, has been more venal than a papal orgy.

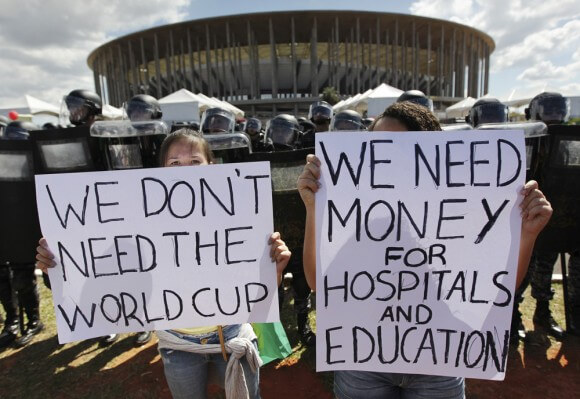

The host country, Brazil, has used the occasion of the World Cup to buttress a long process of neoliberal governance that exacerbates iniquities of race and class. Construction costs for useless stadiums have soared because the price of materials includes a huge markup for graft. Housing and transportation infrastructure is in disarray, but not because of poor engineering; tycoons are content to trade profit for the public good. The low-income and indigent, as usual, are displaced for the benefit of tourists who wish to enjoy sun and samba without the inconvenience of visible poverty.

The World Cup has been lucrative for Brazil—if we limit our definition of Brazil to the political and economic elite. (It’s stunning how often the interests of the elite stand in for the desires of an entire population, though it’s inevitable when oligarchs own media corporations.)

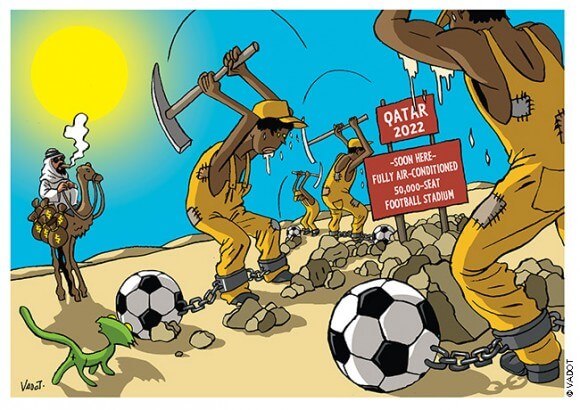

Before anybody gets the idea that Brazil’s World Cup folly is typical Third World corruption, we’ve seen similar shenanigans in London, Athens, Atlanta, and Los Angeles (for the Olympics) and in Germany, South Korea, and Japan (for the World Cup). Reports of exploited foreign labor, a staple of Persian Gulf economies, have already been filed for the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. Russia’s performance at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi doesn’t portend well for its World Cup turn in 2018.

The problems are systemic, a reflection of FIFA’s magisterial presence and the exorbitant demands of the selection process. Malfeasance becomes a necessary feature of the procedures from which hosting bids emerge. Political systems come equipped to handle that necessity.

Hosting countries fleece the poor then make the poor vanish. It’s a natural consequence of polities where values are invested in real estate and not in basic human compassion.

Despite these realities, I will eagerly watch the World Cup, just as I watch college football despite its inherent dishonesty. (Thanks to Daniel Snyder, Jerry Jones, and Roger Goodell, I’ve managed to largely extricate myself from NFL fandom.) I don’t discount the possibility that I’m simply hypocritical or weak-willed. Besides, international soccer and college football are damned exciting.

Still, it’s important to consider our relationships to oppressive institutions, especially when those institutions provide us with a sense of excitement. One way to register objection to Brazil’s excessive graft and displacement of the poor is to bypass the World Cup altogether. It’s a tough thing to ask of the globe’s most passionate fans, so we have to contemplate ways to integrate fandom with political consciousness.

The easiest action for a fan is to be informed about the underbelly of athletic celebration. Information in itself is not transformative, but it helps actuate the process of being an active spectator, by which I mean a fan who engages sport in its ineluctable contexts of race, sexuality, economy, and militarization. Sport has a wonderful ability to direct us toward broader issues of profound social import. It can help render the world a comprehensible space, one that hosts tremendous physical and metaphorical conflict.

The World Cup doesn’t occur in a vacuum. It arises from the same worldly injustices we can easily recognize in other settings (even though these settings aren’t actually separate). The World Cup also performs those worldly injustices; in order to stage a spectacle worthy of corporate approval and the participation of the governmental elite, undesirable social elements need to disappear. Those elements don’t disappear without the exercise of state violence.

This summer, then, enjoy the World Cup. Just remember that when the games end, the real competition remains.

I think the answer to ending these complicit abusive actions by FIFA and local governments begins with your point that fans be “informed about the underbelly of athletic celebration.” Sport is essential to our society and we want to inspire people to continue to develop their talents and adhere to the best of sporting traditions and competition. I’m reminded of the recent scandal in pro basketball where Donald Sterling voiced values that were unacceptable to the majority of our society and especially basketball fans. Once we get to that level of awareness within FIFA perhaps we will see a change.

Sports and politics have imo nothing to do with each other.

How west treated Russian olympics was despicable.

One of the unnoticed problems/issues with America’s ineptitude with taking up world football, instead of the bastardised handball sometimes called “football”, is the inability to use sport with politics when writing about international economics and neoliberalism.

You see this a lot more in Europe, where there is almost a niche of journalists mostly writing about socio-economic issues framed through football, often from a left-wing(not liberal) perspective.

It is a lot easier to engage people on Bolivia’s economics history, say, if their national sport is the same as your country’s.

Neocons talk about political isolationism(i.e not enough wars), but America’s sport isolationism is a bigger issue.