What happens when a person is forced to struggle for years without enough money to support his family, and there is—literally—no way out? Now imagine that same desperation and hopelessness is reverberating across hundreds of thousands of people crammed into a tiny space?

“I tried to control myself and make myself think logically, but something was telling me to continue. Ending my life would be a relief: No one would call for money any more, no problems, no stress.”—Rezeq Abu Setta

There is a strong taboo against suicide in the Gaza Strip, where Islam is the predominant religion. But on February 9, Rezeq Abu Setta, 38 and a father of seven, joined a growing trend in the blockaded Palestinian territory. He attempted suicide.

Abu Setta was one of the estimated 80 Gazans a month who tried to or succeeded in taking their lives in January and February—an alarming increase of 35-40 percent over previous years. And some sources suggest the total may be even higher.

Abu Setta’s story is individual in many respects, but common in one essential way: He could not earn enough money to support his family.

In Abu Setta’s case, he had worked as a guard for the Fatah-affiliated Palestinian president until 2006, when Hamas took over Gaza. In the wake of the dispute between the two political movements, Abu Setta was paid by the Palestinian Authority (controlled by Fatah) to stay home, along with hundreds of other Fatah employees. He continued to receive his salary—until he made a big “mistake.”

“I travelled abroad for one month, just for a break. I knew I should have asked permission, because it was against the law, but it was common practice at that time,” he told me. Abu Setta has been forced to pay for his “transgression” ever since that fateful trip in January 2011.

“My salary was taken from me and my life as well. I accumulated lots of debts and was reduced to borrowing from everyone I could. There are many needs for me and my family. I have seven children in addition to my mother and sister, and they all depend on me. Where can I go? There is no hope or other opportunities. I didn’t get any training in the military that is useful outside, and anyway, there is no work for anyone.”

Tuesday, February 7, should have been a happy day for Abu Setta. His wife delivered their seventh child. But he couldn’t pay for the hospital and since he no longer had a salary, he also had no insurance. “I went to the Ministry of the General Authority of Insurance and Pensions to ask for help in getting vaccinations for my baby. But they said that according to their records, my salary was not cut. I asked what I could do to prove it. They told me to go to my department and bring a letter. But how can I go to Ramallah?”

Abu Setta tried other people and was told to wait for awhile, since the reconciliation process between the two political parties was complicating matters. “But how long do I have to wait? I was told, ‘you waited for five years, you can wait for five months.’ I left.”

On the way home, Abu Setta received a phone call from someone asking for money he had borrowed. “I can’t,” Abu Setta told him. “Just wait until I get my salary back or at least borrow more from someone else.”

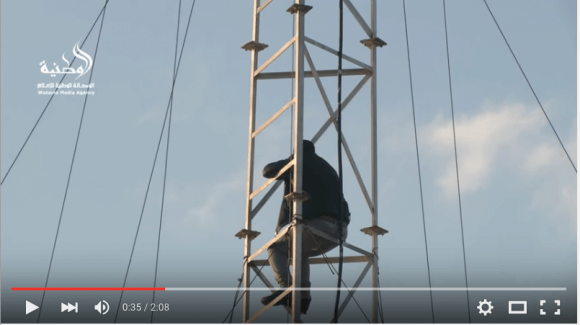

They argued and Abu Setta became stressed and couldn’t think logically. He wanted to end it all. He kept walking and from afar he saw a tower. He said to himself, “What if I climbed it and jumped?” That’s what he decided to do.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FkuIgXLJlTE

When people saw Abu Setta climbing the tower, they called the police. Many members of Fatah, including a senior member of the party, talked to Abu Setta on his mobile phone and promised to solve his problem. But since he had been promised before, he didn’t believe them until his department in Ramallah contacted him through his mobile and backed up the pledges. The prime minister in Gaza, Ismail Haniyeh, and President and Fatah member Mahmoud Abbas even got involved. When officials brought his mother to the scene, Abu Setta cried and climbed down.

“I only asked for my right. I wasn’t asking for charity or a donation,” he says now. “Why should I have had to go to that extent, to endanger my life, in order to have my problem solved? What if I had slipped while I was going up or down? Or what If they didn’t agree and I died? Who would have suffered the most from this? Only my children and family.”

Abu Setta has not yet begun receiving his salary, despite the promises.

With around 1.85 million Palestinians on some 362 square kilometers, Gaza ranks as the sixth most densely populated enclave in the world.

For around 10 years Gaza has been under an Israeli blockade that lately has been worsened by an almost continuous closure of the crossing into Egypt. Israel controls Gaza’s air and maritime space, and six of Gaza’s seven land crossings. It reserves the right to enter Gaza at will with its military and maintains a “no-go” buffer zone along its border with Gaza, where much of the best farmland is located. Gaza is dependent on Israel for its water, electricity, telecommunications and other utilities. Eighty percent of Gazan households now live below the poverty line. Forty-three percent of adult residents are out of work.

According to the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor, suicides and attempted suicides averaged about 25-30 a month in 2013-2015. During January and February of this year, however, reliable statistics indicate that about 80 people per month either tried to kill themselves or succeeded—with some unconfirmed estimates even higher. That’s an increase of 35-40 percent.

“The situation has never been worse,” says Zahia Al-Qarra, MD, a psychiatrist with the Gaza Community Mental Health Program. “In the past, Gazans have always been able to find a way out when it got very bad. They would work in Israel or abroad in Saudi Arabia or Kuwait. Even when those options were not available, they could escape through the tunnels into Egypt. But now that Israel and Egypt have destroyed most of the tunnels, there is no way out. We are trapped in Gaza. Everyone appears to be against us. All of the doors are locked.”

Although suicide is prohibited by Islam, Al-Qarra notes that when a person loses everything and enters the “depression zone,” his or her beliefs and all other restraints “fade away. He looks for salvation in any way possible.”

Al-Qarra added that families in Gaza raise children expecting them to grow up to help support the parents—often bringing great pressure to bear and causing stress. “They tell their children to go look for work, to do something with their lives instead of staying at home doing nothing, etc. But families need to understand that it’s not the fault of their children.”

She added that no one seems to care about young adults and men, channeling most of their resources to women and children. In fact, many young adults find themselves in the “depression zone” and don’t have at least the potential of a happy ending like Abu Setta. Consider the cases of Younes Albureim, 32, and Nedal Arafat, 36, both of Khan Younis in southern Gaza. (Strangely enough, Abu Setta is from Khan Younis as well.)

Younes Albureim

“I started this life and I’m the one who will end it.” These are the last words that Albureim wrote on his Facebook profile before he set himself on fire the next day.

Ten years ago, while he was working to construct a building, Albureim fell from the roof and broke his back. What followed was a years-long struggle to find work he could still do and to afford the series of operations he needed to function.

“His brothers got married, but he didn’t. He said he couldn’t work, and couldn’t even afford himself,” his mother told me, her voice breaking.

The last days of Albureim’s life were the worst, with the steel in his back becoming infected, requiring yet another surgery. His mother said he went to all of the associations, but they all refused to help.

On Friday, February 11, he told his sister, “I will go and burn myself.” She didn’t believe him.

He left his ID with her and went to a fruit shop where he had a smoke. Then he went to a nearby petrol station and bought two liters of gas. He poured the gasoline on his clothes then set himself afire, saying Allahu Akbar (Allah is the greatest). He was burned over 52 percent of his body and died eight days later.

“I’m 60 years old,” his mother told me. “I have never heard of anyone killing or burning himself. My family members all worked and married and had children. I have never seen a young man kill himself. Now, in Gaza, there is no good food or good life; young people can’t afford education even. “

Nedal Arafat

Arafat was unmarried and worked in a grocery store. He often spent his nights there. On February 10, the other employees couldn’t find him. They called him but his mobile was turned off. They went to a room in which he often found refuge, but the door was locked from the inside. They knocked, but there was no reply. They broke down the door, finding Arafat hanging from the ceiling.

I visited his home with my colleague from We Are Not Numbers. We told Arafat’s father and brother that the project is sponsored by the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor. Mohammed, the brother, bitterly commented, “Human rights? Really? Do you believe they still exist? Do you think there is any role for human rights in this world?”

“Nedal was unmarried and had no children,” said his father. “What could he do? He spent his days looking for a better income. He went to associations to look for job, but they never called. All the doors were locked and he didn’t see a way out.”

Half of the Arafat house was destroyed during the war of 2014, including Nedal’s room and all of his belongings.

His father added that Mohammed is in his 30s as well and also has no life. “None of my children has,” he said. “We can’t help them. Nedal was depressed he didn’t have anything that would make this life worth living. But I never thought he would do this to himself. “

When I asked him what message he would like to send the world, he said, “I don’t want to send any messages. They know what’s happening.”

Interesting article to publish considering the recent suicide of a 10yo aboriginal child in progressive, highly developed, first world white nation of Australia, who didn’t even need to use fancy blockades and apartheid to render their undesirables of their will to live. Maybe Israel should stop trying to copy the Nazis and start learning a few things from Australia.

Not to be too cynical, but I wonder how many of the people getting shot for trying to stab Israelis are really committing suicide by cop.

I know it’s not all of them, but by now the stabbers must know what is most likely to happen to them when they get caught with a knife in their hands.

This is my message to those who despair: Protest, resist, but don’t give those Zionist bastards not even a milligram of satisfaction. Don’t help advance their kill quota!

In Gaza a reliable method would be to go up near the barrier with Israel. There are many methods of committing suicide and most are not recognized as such.

When I asked him what message he would like to send the world, he said, “I don’t want to send any messages. They know what’s happening.”

That is the horrible truth.