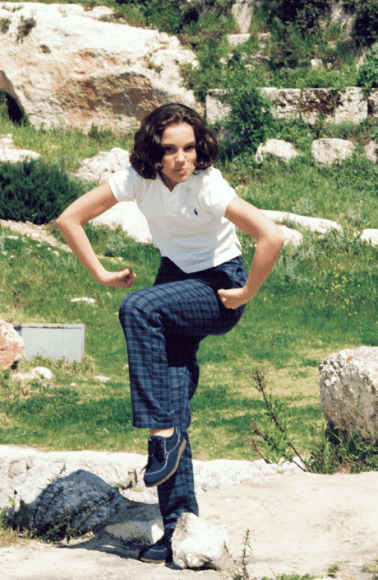

Natalie Portman, supermodel, Oscar winning actress, has written, directed, and stars in a recent film adaptation of Amos Oz’s autobiographical novel, A Tale of Love and Darkness (2002). Amos Oz, the celebrated writer of 13 novels, and 25 other books, has been published in 42 languages. Tale of Love and Darkness traces his parents’ journey to Palestine, and the formative relationship with his mother, Fania Mussman who committed suicide when Amos was just 12 years old. We saw Portman’s film last night at the Castro in San Francisco, on the third day of the Jewish Film Festival currently in progress here. The film is slated for a wider theatrical release in the United States next month.

Portman is smart, complex, famous, and not entirely comfortable with her celebrity. In interviews her hands interact nervously: she knows how to hold herself, and knows just what to say in order to play the game that’s made her a wealthy woman, but she looks uncomfortable with that game. She’s nervous on screen when not in character as model or actress. It’s a discomfort that serves her well playing the role of Amos Oz’s brilliant, disturbed mother.

It’s clear why Portman was interested in making this film. The family histories of Portman and Oz are vaguely parallel, and together they encompass the essence of the 20th century Jewish narrative: emigration to Palestine, emigration to the United States, the Holocaust, formation of the state of Israel, and the complex relationship between Israel and Jews in the diaspora, and Israel and the Palestinians. It’s this overarching narrative that gives depth to this film and makes it special, even if it’s not perfect.

Both Oz and Portman changed their names: Oz [the word means “strength” or “might” in Hebrew] adopted his new name as he left home at age 14 to become a writer on Kibbutz Hulda; Portman, born Neta-Lee Hershlag, adopted the maiden name of her paternal grandmother (presumably) to facilitate her film career. The film intimately links Oz and Portman in a loving inverted parent-child relationship.

Portman’s paternal grandparents emigrated to Palestine from Poland in the 1930’s while her maternal grandparents emigrated to the United States from Poland and Austria. Her parents met at Ohio State University and her mother followed her father back to Israel where Portman was born in 1981. The family moved back to the United States when she was three years old.

Oz was born Amos Klausner in Jerusalem in 1939 where his parents met at the Hebrew University. His mother, Fania Mussman, was born to a wealthy mill owner in Rivne (82 miles west of Kiev). Fania and her two sisters attended a Hebrew Zionist grade school in Rivne. Later she studied history and philosophy at Charles University in Prague, and after her father’s business collapsed in the Great Depression, the family emigrated to Palestine and she continued her studies at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Oz’s father, Yehuda Arieh Klausner, studied history and literature at the university in Vilnius. His right wing revisionist Zionist family moved from there to Palestine in the 1930’s.

The Mussmans and Klausners were served well by their Zionism. They may not have cared for the dusty and unrefined streets of Jerusalem when they arrived, but it was better than the alternative. Of approximately 210,000 Jews living in Lithuania at the start of World War II, almost all (approximately 195,000) perished in the Holocaust. In Rivne, the Germans shot 23,000 men, women, and children in the forest on November 6-8, 1941. The region was ground zero for approximately half of the Holocaust.

The film omits the biographical story of how the families came to be in Jerusalem. It opens with mother and son in bed, in the dark, telling stories. It’s 1945 and Amos is six years old. There is tension in the house, vaguely connected with a difference in the parents’ Zionism. Yehuda understands implicitly the coming assertion of Jewish power and what it will mean for the Arabs. “Our nation is standing at the gate,” he says. Fania sees no gate, “there’s an abyss,” she says. In her mind she sees the streets of Rivne emptied of life, and she is terrified. In her dreams she fantasizes a virile labor Zionist working the land in peace–no guns. To be sensitive is more important than to be honest, Fania counseled her son.

On the way to school Jewish children casually vandalize the hanging laundry of Palestinians.

What does it mean “to be sensitive” in the context of Zionism? Does it imply sharing the land? It would seem so. The Palestinian author and critic, Samir El-Youssef, observes that even prior to 1948, Jews sought to share the land by living apart. Amos Oz has been advocating to complete this separation and to make it permanent through a “two-state-solution.” But such a separation can never be “sensitive,” or just, says El-Youssef: with the passage of time, future generations will naturally overlap and want to integrate in the land. He concluded an article in the Jewish Quarterly in 2004 as follows:

The problem, at least for Oz and those who believe in peace on the basis of the two-state solution, is that separation as a policy – like every policy which needs to be imposed from above – entails the use of violent means: waging wars, raising walls, removing settlers, slamming the doors in the face of Palestinian workers trying to earn their living in Israel, etc. But couldn’t such a policy, one might ask, be achieved peacefully? No, because the two states proposed by Oz and others are unequal states on every possible form of comparison. And unequal states are unlikely to make good neighbours even if the fences are good.

A scene early in the film appears to illustrate this point. The family is invited to a party at the home of a rich Arab in Jerusalem. On the way Yehuda lectures this son not to accept food that is offered, and to be polite. Yehuda appears to be counseling separation, so as not to upset relations between the Jews and Arabs. When they arrive, Amos is sent to the garden to play with the host’s children. In the garden he finds an attractive, intelligent, and ambitious girl his own age and her younger brother. But Amos does not know how to play. He knows how to talk: “There’s room here for both peoples,” he volunteers out of the blue. He is not oblivious to the implied threat in what he says. The girl coaxes him to climb a tree. Reaching the branch that supports the swing, he seizes it and shakes it violently with mindless animal aggression. It’s vaguely frightening–and it causes an accident that harms the younger child. The parents understand this for the metaphor that it is. Dread is in the air.

Seventy years ago, on July 22, 1946, the Zionist underground blew up the southern wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, killing 91 and injuring 46 more. In the film the blast breaks up an intimate family outing with Fania gently stroking the heads of both father and son lying on the grass in the park. We don’t see the hotel. It’s like a rumor. More upheaval follows. There is a picture of a British lout of a soldier slouching on his jeep. It’s a picture of occupation. Any occupation. Annoying. Entitled. It makes manifest the Zionist desire to seize power and rid themselves of the British, because they can; but the irony of the Israeli occupation over Palestinians is not lost.

An abyss, said Fania. And as time goes on she withdraws more and more into depression. Her stories grow darker: a drowning girl, a young Polish officer shooting himself.

The UN declaration of partition of Palestine on November 29, 1947 brought the moment to its crisis. The film shows a sniper killing of Fania’s friend as she hangs laundry; a sniper killing of a young boy kicking a soccer ball; Fania establishing a bomb shelter in the Klausner basement. There is a small amount of archive war footage. We don’t see any of the Palestinian suffering. We see Oz collecting bottles to be used as Molotov cocktails. And Portman shows us Oz remembering the bright young Palestinian girl from the garden in Jerusalem. He instinctively knows that this war has robbed her of her future. The war has separated these societies into separate camps: occupier and occupied.

What did Fania think? Would she have agreed with El-Youssef? “Nobody knows anything about anyone,” she said to her son. And we don’t know if her melancholia and eventual suicide was the result of World War II and the resulting emptiness in Rivne, the tragedy of Zioninsm as she saw it unfold, or something about her constitution. We do know that she provided inspiration for her son, and now to Natalie Portman, and that as long as we can hear her counsel to choose to “be sensitive” as an overarching value, there’s hope.

The film co-stars Gilad Kahana as Arieh Klausner, Amir Tessler (Amos Oz as a child), Yonatan Shirai (Amos Oz as a teenager), Makram Khoury, Shira Haas, Neta Riskin, and Asia Naifeld. The film will be shown again as part of the festival on August 4 at the Rhoda Repertory theater in Berkeley.

I’ll be impressed with her when she helps produce a movie about the Nakba and the decades long occupation of Palestine. Till Hollywood starts making movies about the genocides and tragedies of other peoples, I refuse to watch any Holocaust related movies, and I will not watch the WW2, I mean, the History Channel.

Summary: be “sensitive” and make sure you keep as much ad you can of other people’s stolen land.

Shouldn’t this guy have published this in any Zionist paper, where he would be met with approval?

Natalie Portman was in a 2005 movie called the Free Zone. I got that the Conflict is bad and that we need peace, but did not really get what the movie was trying to say, particularly the ending where it focuses on her face for maybe 5 minutes when she is crying and it plays the same chorus over and over about “the lamb”.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FuBo5z0fr8A

The Free Zone

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_Zone_(film)

Do you understand what the movie is trying to say at that part?

Very interesting. Much thanks. I look forward to seeing the film, and I ordered the book.

I have always very much liked both Amos Oz and Natalie Portman.

Amos Oz is one of our foremost writers, and also known for his outspoken commitment to the Israeli peace movement.

Natalie Portman- who can forget her debut in “Leon”?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nVYFOlVB-Uo