This summer, I’ve been going through crates of old albums in my parent’s basement. Some of the records have triggered more memories than others. A few remind me of college, like Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell. I remember making out with a guy in my dorm room, in 1988, to the song, “You Took the Words Right Out Of My Mouth (Hot Summer Night).” I also found Joan Armatrading’s Show Some Emotion, which I also remember playing after the Meat Loaf guy dumped me. Others, like Simon and Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits, remind me of the summers I spent at Habonim Dror, the Zionist summer camp modeled after a kibbutz that I attended in the 1980’s. Often we’d listen to “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” or “America,” or “The Boxer,” while cleaning bathrooms or making breakfast or building a bonfire.

I had forgotten about an obscure record that I found next to my Simon and Garfunkel albums, The Parvarim sing Simon and Garfunkel in Hebrew. The Parvarim were an Israeli duo, Yossi Hurie and Nisim Menachem. They started their career in the 1950s, primarily singing Ladino ballads and Shabbat songs, but were most famous for their Simon and Garfunkel covers from the 1970’s. The music sounds remarkably like Simon and Garfunkel, only in Hebrew. The album was helpful to me when I was studying Hebrew, and, later, when I taught Hebrew at a public high school. I played the album the other day, and was startled by the memories it stirred in me of when I was a Zionist–mostly feelings of loss–particularly when I played “Sounds of Silence,” and “America.”

Later that evening, August 10, I attended Rabbi Brant Rosen’s book launch for the second edition of his 2012 book, Wrestling in the Daylight: A Rabbi’s Path to Palestinian Solidarity, released this year. Rosen used to be a Zionist, too, and we’ve often talked about the process we’ve both gone through to undo the Zionist upbringing we both had. Rosen, who was the Rabbi at the Jewish Reconstructionist Synagogue (JRC) in Evanston, Illinois, from 1998-2014, was one of the first Jews I approached when I began to question what I had learned and believed growing up about Zionism and Israel.

I remember sitting in his office at JRC, feeling nauseous, scared that what I was learning about–indeed, that Israel is in fact Palestine and was taken from Palestinians–would cause me to question everything else about my life. So much of my identity had been formed around my love for Israel. I couldn’t talk to my family about this. I worried that students from the school where I taught Hebrew, and their parents, were in the building and could somehow hear our conversation, even though the door to his office was closed.

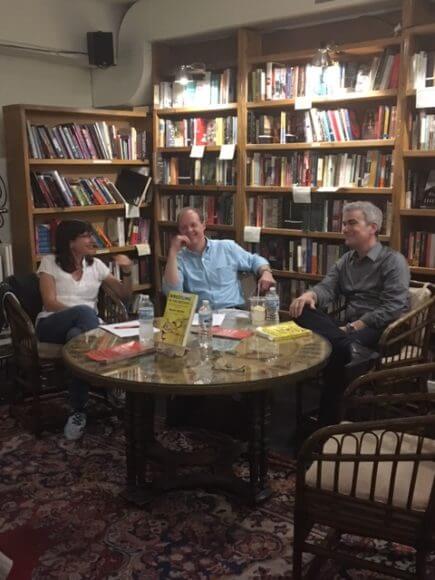

Rosen talked about the need for Jews to disentangle Judaism and Zionism, too, at the reading last week, held at the independent bookstore, Bookends and Beginnings, in Evanston. About 50 people showed up to the event. Rosen’s book is a collection of posts and comments from his blog, Shalom Rav. Rosen intentionally put comments from readers of his blog in the book because he wanted to show a back-and-forth conversation about Israel/Palestine. “I thought that the blog could be a record of how to have a good conversation,” Rosen explained. Rosen began Shalom Rav in 2006. The posts in his book chronicle his changing feelings towards Israel/Palestine–and his increasing outrage at Israel’s 2008 Operation Cast Lead assault on Gaza–while serving as the congregational Rabbi at the Reconstructionist Congregation.

“I raised a little dust at the congregation,” Rosen mused, as he talked about the painful decision he made to leave JRC in 2014. I was a member of JRC for several years, and I remember the arc of Rosen’s career as the Rabbi. We joke now how we both believed, when we were young, that we were going to move to Israel and pick tomatoes in a field for the rest of our lives. Our love for Israel was real. Then, through a painful process, we realized that the myth of Israel we had loved was very different from the reality. Since, we’ve learned how vital it is to separate Judaism from Zionism.

“Zionism is nationalism and not Judaism,” Rosen said at the reading. He also explained that he intentionally inserted comments in his book that both vehemently support and oppose his views on Israel/Palestine. “You are truly a sick and twisted individual devoid of any logical moral sense,” one commenter, Cynthia (no last name given), wrote. Andy White, cofounder of Chicago’s Lookingglass Theatre, and Gwen Macsai, author of Lipshtick and host of Chicago’s WBEZ’s Re:sound, joined Rosen in an evening organized as a readers-theater format and discussion. Rosen read selections of his blog posts, while White and Macsai took turns reading the comments Rosen included in the book.

The first edition of Rosen’s book ended on a hopeful note; Rosen was still the congregational Rabbi at JRC. Since the publication of the book, however, Rosen began to feel like he couldn’t keep self-censoring his feelings about what was happening in Israel/Palestine. “My activism on Israel/Palestine made things challenging for a number of years,” Rosen explained. His own relationship to Israel/Palestine has continued to evolve. “I could not support or condone or rationalize Israel’s actions away.”

In 2010, four years before Rosen would leave JRC, he organized the first congregational trip to Israel and Palestine. I was one of 20 people who attended. The trip was a dual-narrative tour through Mejdi, facilitated by an Israeli and a Palestinian. Rosen had a deep understanding of the political significance of Jews going to the West Bank for the first time, especially on a synagogue trip.

I remember the Saturday morning in the hotel in East Jerusalem. Rosen had coordinated a Shabbat service in one of the meeting rooms in the hotel. We sat in a circle. Someone sang. Most closed their eyes. Brant hummed to the singing. I opened my eyes for a second in the midst of the moment and looked around the room. I had been to the West Bank before, but not with a group of Jews. I remember getting a bit choked up, overwhelmed to be in East Jerusalem on Shabbat morning with other Jews who wanted to stay with Palestinians up north near Jenin and in the Deheishe refugee camp. And then, embarrassed, I closed my eyes again, feeling as though I had been a voyeur in a sacred space that didn’t need to be seen.

After the trip, Rosen and I were both hopeful there would be another trip the following year for other JRC members. It didn’t happen. Things got tense. When Rosen left, I left too. A fearful silence was descending on American congregations. When one Pennsylvania Reform temple was hiring a rabbi last year, they put a clause in her contract that she not talk about Israel from the pulpit. (She reportedly refused to agree, and got the job anyway.)

To have a second edition of a book come out for a writer is a mark of success. Rosen’s book is this and more; the second edition explains his decision to leave the JRC. “I used to be working the inside game,” Rosen said of his time at the JRC. “Now I feel like I’m doing the outside game.” He began working for the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), and co-founded a new congregation, Tzedek Chicago. “The new congregation does not celebrate political nationalism with Jewish tradition,” Rosen explained. Tzedek Chicago is “an intentional community that is decidedly not Zionist.”

One post that brought out particularly extreme comments from readers was his reimagining of the traditional Tisha B’Av liturgy (mourning the destruction of the temples), which he named, “A Lamentation of Gaza.” “HOW DARE YOU! call yourself a Jew, let alone a Rabbi,” one commenter, Irwin W.D., wrote. “You low class piece of excrement! You should be excommunicated.” Robin S., another commenter wrote in response to the same post, “This is so beautiful and sad. Thank you for your posts and your commitment to speaking the truth.”

I remember when Rosen posted his “Lamentation of Gaza” in August 2014. Around the same time, he had also organized a gathering at a friend’s home for those who were feeling infuriated at yet another Israeli onslaught. I went to this group meeting and was heartened by the strong emotions expressed by other Jews who were outraged at what Israel was doing in our name. Many felt there were no Jewish institutions where they could express their frustration. Some of us said we couldn’t express it in our families.

At Rosen’s book launch, he reflected on the 2014 war on Gaza. “The only time Gazan dead were mentioned,” Rosen explained, “were as human shields.” Rosen talked about his involvement in several nonviolent actions in Chicago at the time of the Gaza war as redemptive.

“My participation was a sacred action,” Rosen said. “We were protesting war crimes being acted in our name.”

White and Macsai read a few more comments. They were difficult to hear. “You are a prince of the Jewish freak show,” David C. said. “SHAME ON YOU. You are not a rabbi. I want to see if you have the guts to post this in full, you sick freak.” After, Rosen stood up. He took a breath, then said, “It’s painful to hear the words that were written in the moment.” I could see the sting in his face when he said this.

Hearing such nasty comments read at Rosen’s reading reminded me of some of the heat I got when I was teaching Hebrew in a large public high school several years ago. I had started teaching the language as an ardent Zionist. I ordered posters for my classroom from the Youth Aliyah organization that said things like, “Your soul is here. Bring your body over.” In the poster, a woman sits alone on the beach looking at the sea. We only see her head and back from behind, and she’s in a sexy white bathing suit. She’s nameless and faceless and could be any woman–as long as she’s Jewish–reflecting and gazing into the water. Parents wanted me to do Israel-advocacy work in the classroom. Some wanted me to organize a trip to Israel with my students. As a Zionist, I didn’t mind. Zionist organizations like JUF, JNF, and Shorashim organized field trips with other Hebrew classes from other local schools.

I remember one field trip in particular, though, after I began questioning my feelings towards Israel. Israeli soldiers spoke about how much Israel needed the students. “You can’t ever abandon Israel,” one soldier said. “Everyone is out to get us.” Most of the soldiers had American accents but donned the green IDF uniform. My students swooned. I overheard one student say, “He’s just so hot!” I remember thinking this, too, when I first met Israeli soldiers. Later, I’d understand the soldier to be a symbol of oppression. Knowing this now, it’s hard to admit that I bought into it, too–this trope of militaristic sexualization–when I was in high school.

At the field trip, Israelis played songs that students recognized from their Jewish summer camps and Birthright trips. One song, “Shir HaShalom,” caused dozens of students to drop everything and put their arms around each other and sway to the music. The other Hebrew teachers taught Israeli folk dances. Everyone ate falafel and hummus–Israel’s “national food”–on blue and white plates. Blue Jewish stars were printed on white napkins. Blue and white plastic silverware sat in large bins on top of blue and white tablecloths. Students crunched on Bamba and reminisced about eating it in Israel.

On the bus ride back to school, the soldiers walked up and down the aisle asking students–who were riding the high from the field trip–to add their name and email to a list. They weren’t 18 years old; I told the soldiers it was illegal to ask for their personal information. The soldiers backed off. I had won a minuscule victory that afternoon, but the power of the Israel lobby would keep on coming. When we got back to school, I lectured my students about signing their name without knowing what it would be used for. One student agreed; most were sold on Israel. “When’s the next event?” one asked.

“I think I’m losing my fucking mind,” I told Rosen soon after the field trip. I understood the love my students felt for Israel. I was one of them when I was their age. I swayed to peace songs too. But now it looked to me like some weird cult.

As I began to identify with anti-Zionism, I felt a block with the Hebrew language. I became a bad Hebrew teacher. I had gone from loving the language to discovering I had been teaching a language of occupation. Years later, a friend would send me materials from the organization, Zochrot, written in Hebrew about the occupation. I re-entered the language this way, reading about anti-Zionism in Hebrew. At the time, though, I got into some trouble as I began bringing in Palestinian narratives into the Hebrew classroom.

On a trip to Israel and Palestine during that year’s summer break, I had bought a poster from the Alternative Information Center that showed the route of the apartheid wall and checkpoints. I showed my Department Chair. He advised against my putting it in my classroom next to the woman gazing at the sea. “You don’t want to know what these parents will do to you,” he confided in me. The next year–I had taught Hebrew there for seven years–a school board member’s daughter decided she wanted to teach Hebrew. As often happens in public education, I was pushed out with no explanation; the message, though, was clear.

I struggle with describing these feelings, even now, trying to write this essay. I often write about the shame I have felt to move through a paradigm shift, to have an epiphany of Palestine, while Palestinians are suffering–and, too, while Palestinians have long been writing about this. Rosen was one of the only Jews I knew at the time who I could talk to about feeling duped by people I loved and trusted the most. I was understanding that Zionism was a form of racist nationalism. I knew I had to disentangle it from Judaism. But I felt lost, alone, and not sure what to do, or how to be, with this new knowledge.

+ + +

It’s fitting that while writing this I’m listening to a song from another album I found in my parent’s basement this summer, “Helpless,” by Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. I hear the words, “In my mind, I still need a place to go, / All my changes were there.” And I think about how many of my changes occurred in Jewish Zionist spaces like camp and Hebrew class and trips to Israel, over “there.” We were forming our identity “there.” We grew up and fooled around and fell in love and explored our sexuality and broke up and fell in love again when we were “there,” and not “here.”

None of us had a real chance with each other over “there,” of course, since our first love, our initial loyalty, was always to Israel, whether we were “there” or “here.” And anyone who stayed together was engaged in some kind of distorted menage-a-trois–a Zionist trinity, perhaps?–with Israel as the third partner. My husband teases me, telling me only I would take a CSNY song and make it about Israel/Palestine. He’s right; it’s still such a big part of who I am. But the song is about a town in north Ontario, not Israel, and the place we still need to go, as the song suggests, is not anywhere, really, but “in my mind.”

One of the many things I’ve learned from knowing Rosen for many years is that the process of undoing one’s Zionism is never over. And it’s painful. Now, as he stands in solidarity with Palestinians, he manages the pain, but it won’t ever go away completely. Rosen is an unwavering leader; he feels the pain of having changed his worldview, but he never lets it deter the work he is called to do. He stands before a crowd, listens to the vitriol written about him, and leads with his vulnerability despite–or perhaps within–the pain he has felt. “The time for convincing is over,” he said. “It is now time to mobilize a mass movement.”

It’s still painful for me, too, even when I listen to old albums that I haven’t thought about or played for 20 years. I just listened to The Parvarim’s Hebrew rendition of “April Come She Will.” I’ll make huge leaps, again–it comes easy to me–connecting the lyrics back to Israel. Though I see it for the occupying, racist, colonialist, nationalistic state it is, Israel remains my first love. “A love once new has now grown old,” they sing, whose voices I still remember.

Wow Liz, thank you so much for sharing your story, with all of its heartfelt emotion and the accompanying rollercoaster ride and life’s learned wisdom.

I wonder how many old Germans struggle with fond memories of their salad days as teens and young adults in the Hitler Jugend and BundesDeutschen Maedchen? What are they feeling, watching video news of Charlottesville, etc?

Liz,

I have the same Parvarim Album too. I hope you can move out of the eclipse of Brant Rosen and come back to our Jewish Community.