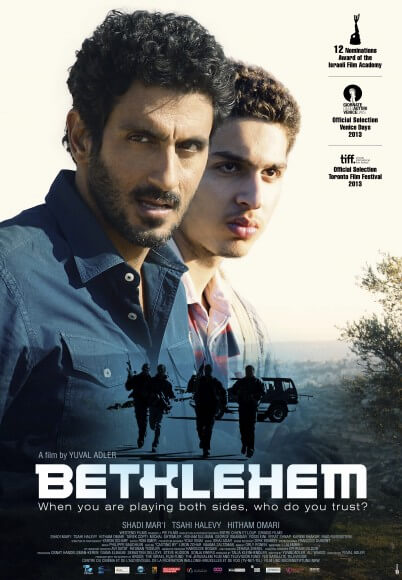

Bethlehem International Trailer from WestEnd Films on Vimeo.

The theatre was packed to the rims, and the audience eager. The film has already won Venice and Haifa, and while we watched it, also took the Ophir prize (nicknamed the Israeli Oscars) for Best Film. Ninety-nine minutes later, the screen cut to black, the credits rolled, and we all rose, dazed, shocked, enthralled. Cell phones were kept in silent mode, and people were quietly shuffling out, starting muffled conversations about the film. Behind me a young man asked his girlfriend “so what is the conclusion?” She paused for a second, and then replied: “the conclusion is that you cannot trust the Arabs.”

I wasn’t sure if she said is seriously, cynically, or flippantly, and I spent some time trying to sort it out, then realizing that her intention did not really matter. It did not matter since the film’s conclusion is, indeed, that you cannot trust the Arabs.

Adler argues that he was interested in the realistic psychological relationship between the operator and his informant, that he wanted to focus on “ a few characters […] people whose lives are extreme because of it [the conflict].“ A tight script, casting of non-professional actors, and the precise cinematography of Yaron Sharf, yield the realism that Adler was after. But realism should not be confused with reality, and the plot, as well as the psychological profiles of the characters, are certainly political.

Throughout the film, we see the paternal affection Razi expresses towards Sanfur. Razi not only cares for him, but confesses that he spends more time with Sanfur than with his own children. When Sanfur is wounded, it is Razi who sits by his hospital bed, presenting an antidote to the ever-scolding Palestinian father. [Needless to say, as an informant, Sanfur receives medical care in Israel, so his West Bank family is not allowed to be with him, even if he wanted them to]. Against the backdrop of this intimate relationship, we find out in the middle of the film that Sanfur has managed –under Razi’s nose — to transfer Hamas funds to his brother Ibrahim, the man Razi is after. Razi is not only betrayed, but humiliated professionally in front of his superiors, and from this point on, he makes a series of judgment mistakes, which eventually lead to the tragic ending.

In contrast, Sanfur has little dramatic agency, and is mostly the victim of his circumstances: under the pressure cooker of Razi, in the shadow of his militant older brother, and finally at the mercy (or not) of Badawi, the new leader of the Al Aqsa Brigades cell. Only in passing do we learn that Sanfur was recruited when he was fifteen. Razi arrested his father, and threatened a long detention, unless Sanfur became an informant, and the child complied. The narrative economy of the film emphasizes the affection Razi feels towards Sanfur, and does not dwell on the fact that Sanfur had no choice but to enter into this dubious relationship . Once discovered by his community, this collaboration becomes Sanfur’s death sentence, and peculiarly, the film ends before its own logical narrative closure. All those filmic choices render Sanfur a support character, and — intentionally or not — place Razi as the tragic protagonist of the film, a new, even ingenious, Israeli crucifix.

Ironically, the film pitches itself as if Sanfur is the main character, and Tsahi Halevi, who plays Razi, won the Ophir prize for Best Supporting Actor. Indeed, one reviewer at TIFF described the film as a film that “delineates the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through the eyes of a Palestinian teen, Sanfur, who at film’s outset is boldly protesting to his peers that he’s got the nerve to take a bullet to the chest (aided by a protective vest presumably looted from Israeli officers). “ But in the Ha’aretz interview, Adler said that “we (himself and Ali Waked, the script co-writer) decided to write the script, to show how the security agent lives, and we will tell the story of the triangle, the SHABAK agent, the Al Aqsa senior, and the child that is caught between them” (my emphasis). Intentionally or not, Adler admits – that, which is plainly clear narratively — that the main character is Razi.

And what is the main conflict our main character experiences? It is an egoistic desire to compete with his superior (Levi), and to contain and control his inferior (Sanfur). Not once do we see Razi contemplate the context of his actions and decisions. In Steven Spielberg’s Munich — which is a one long blood bath of the political action genre — the main character, a Mossad agent named Avner, has a mental breakdown at the films’ end. The psychological and ideological crisis is summed up in his own words as “violence begets violence.” Razi, unfortunately, does not even begin to question his role in the political configuration. If Adler sincerely wanted “to present the story of the triangle” he should have chosen an adult as Razi’s Palestinian counterpart; alternatively, he could have portrayed Badawi as a sophisticated leader. In either case, Razi’s privileged position would have been complicated, and the film would have been much more interesting both psychologically and politically.

In stark contrast to the compassionate and principled Razi, Sanfur’s brother, Ibrahim, is a commander of an Al Aqsa Brigade cell in Bethlehem, and at the film’s opening he organizes and executes a suicide operation in Jerusalem. The Brigade is a secular militant movement, associated with the PLO. However, in the film’s plot, Ibrahim is funded by the Hamas, thus portraying him as politically malleable. Ibrahim is seen in the film only in one scene, with mundane dialogue lines, so his character is structured as a shallow antagonist. In contrast, his deputy, Badawi (literally, a Bedouin), is worth our attention. He is brutally violent, kills his own men when they seem un-loyal, threatens his way out of Palestinian police detention, but lacks the ability to lead politically. Badawi, alongside the corrupt PLO leadership, and most of the Palestinians males on screen (including children), are all violent, irrational, conniving, willing to compromise their values – if they have any — and are unpredictable.

Since much of the film takes place in Bethlehem, with the abundant Palestinian violence — mostly directed towards other Palestinians — we should be reminded of what is missing from the film, namely, the occupation. We do not see checkpoints (although we hear of Sanfur sneaking around them); we do not see the extreme economic deprivation, nor the violence and severe restriction of Palestinian movement, including the eight meter high concrete wall that surrounds Bethlehem, and is seen from anywhere inside it. When we do see the army in action, in an eighteen minute battle scene, it is shot almost entirely from the perspective of the soldiers, while they are being under stone throwing attack. These cinematic choices carry ideological implications, and they encourage audiences to identify – psychologically, cinematically, and ideologically — with Razi, or with Israel’s security apparatus. Rather than shying away from politics, the film makes a blunt political statement, one that aligns with the hegemonic Israeli hawkish perspective.

An action film rarely ends without the death of one of the protagonists. In Bethelehem, the final confrontation could have ended in one of three ways. Not to spoil the ending, but to guide the viewing, I argue that the scenario the film chose cements a political conservatism, if not out and out exposes the film as reactionary. If Adler chose either of the two other possibilities, the film’s final message would have been much more complex politically. But it is precisely this ending that makes the film so palatable to Israelis.

The film is Israel’s official selection to the Academy Awards, and I imagine will be a real contender. Lesley Felperin writes in Variety (at Venice): “the plot sifts through the moral complexities of the situation in such a way as to seem admirably evenhanded, although there are bound to be partisan viewers from both camps who will strive to find offense somewhere.” I would argue that the film would seem even-handed, or Palestinian focused, only to those who are not the victims of Israel’s forty-six years long occupation. Just as with Lebanon, Waltz With Bashir, Walk on Water, and a dozen other recent titles, Israeli cinema managed to turn its security industry personnel into the victims, rather than first, and foremost, the perpetrators of violence. And what a better place than Bethlehem to celebrate this victimhood?

you have to wonder when the Israelis will stop milking suicide bombing

the Israelis butchered more people in 2.5 weeks (1400ish ppl) than ALL suicide attacks (not just ‘bombings’) in 30 years (800ish ppl)

how often do Zionists whitewash Palestinian suffering and attention directed toward them and the conflict by diverting to [insert beleaguered bloody conflict/country]?

lets do the same to the Israelis – who suffer a fraction as much as their Palestinian victims

after all if Palestinian suffering is meaningless, as the Zio-Trolls and Jewish supremacists/racists claim – then surely Israeli suffering is even more meaningless

Fink in Defamation

My favourite part is here where he talks about how Zionism uses the cover of the suffering of WW2 to beat the crap out of the Palestinians

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yKpmnSY6WFY&list=PL5499CA3997F5617B

Dersh attacks the religious establishment in Israel

Get some popcorn in and sit back

http://www.haaretz.com/jewish-world/jewish-world-news/1.557537

” Attorney Alan Dershowitz is asking President Shimon Peres to intervene in the case of the apparent blacklisting of Rabbi Avi Weiss by Israel’s Chief Rabbinate.

The Rabbinate recently rejected a letter by Weiss vouching for the Jewish credentials of an American couple seeking to wed in Israel (the Rabbinate requires a letter from an Orthodox rabbi certifying one’s Jewish identity in cases of non-Israelis seeking to immigrate or marry in Israel).

Weiss, the spiritual leader of the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale and founder of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah, has been the subject of controversy in recent years for pushing the envelope when it comes to ordaining Orthodox women as clergy. After learning that his credentials were being challenged by the Rabbinate, Weiss penned an opinion article in the Jerusalem Post on November 5 calling on Israel to end the Rabbinate’s “monopoly on religious dictates of the state.”

Here’s what Dershowitz, a practicing criminal and constitutional lawyer, wrote to Peres on Monday:

Rabbi Weiss is one of the foremost Modern Open Orthodox rabbis in America and one of the strongest advocates anywhere for the State of Israel. As a person – I am deeply saddened by the pubic shaming of my friend, Rabbi Avraham Weiss, the leader of a flagship Orthodox congregation.

As a Jew – I understand that today more than ever before there is a chasm between the Jews of the United States and the religious institutions in Israel. This is clearly expressed in the rejection of the most elementary and fundamental testimonies and confirmations. I am disturbed by this, and by its ramifications, and call upon the leaders of Israel to first understand that there is a serious problem which demands attention, and to understand that they mustn’t bend to baseless religious tyranny.

As a lawyer – I am forced to see yet again how basic rights, such as the right to marriage, the right to self-definition and the right of religion, are trampled by none other than the Israeli democracy we value so. This is yet another result of the rather unsuccessful fusion of Religious law and Israeli law, and the problem seems to only intensify over time.

I turn to you, Mr. President, knowing that you have always been a voice of moral courage – to intervene in this matter. “

The best police and informer movie from South Africa, Mapantsula, a community theater project was the start of this wonderful piece, foolishly its mostly contextualization, the white characters have few redeeming qualities, as the ‘other’ can not ever, by definition, be humanized, or its not the “other”, a conundrum as yet unsolved in the Republic, as Cyril Ramaphosa has discovered that black proletarians are all criminals, white is not a colour, its an attitude.

I would recommend Mapantsula for those who struggle with the tension between resistance and collaboration, its an endless battle, which in the end they, those “others”, always lose, or is it loose.

http://youtu.be/kY8JU2m__bI

Naaman seems to have wanted to see a different film than the one that

was co-written by an Israeli Jew and an Israeli Arab. Naaman skips

over the fact that this film is actually a working collaboration (sic)

between a Jew and an Arab. She by this glaring omission gives us the

false impression that this film follows a pattern where “Israeli

cinema managed to turn its security industry personnel into the

victims, rather than first, and foremost, the perpetrators of

violence”.

Waked says (refer

http://www.haaretz.com/culture/arts-leisure/.premium-1.553718 )

“The cowriter of the award-winning Israeli film ‘Bethlehem’ on why he painted such a dark portrait of Palestinian society…..working on ‘Bethlehem’ was a ‘corrective experience’ that gave him a chance to present a close-up portrait of Palestinian life in the West Bank warts and all. Corruption, extortion, betrayal and internecine rivalries are rife in the film as the second intifada waned around 2004-2005.”

Waked is unfazed by the attack by Gideon Levy whom he suggests totally misread the film. He said “I don’t think it portrays one side or the other as all bad. As a Palestinian, I would not be capable of demonizing my own people.” He defends Badawi in the film “as being ‘a man of integrity, an uncompromising patriot’ whose sometimes vicious acts are motivated not by greed or lust for power, but by his total devotion to the struggle against Israel.”

Naaman seems to think that if the director Adler had wanted “to

present the story of the triangle” that he should have done it

differently. Obviously Naaman had a personal preference for a

cinematic triangle with her specific dimensions, but that would have

been another film and not one that showed the intriguing interplay

between the main protagonists in Bethlehem.

Not wanting to spoil the film for those who haven’t seen it, Naaman

fails to point out the failings of Razi who is not painted as a ‘good’

Israeli by any means – lying to his superiors and using the

Palestinian boy Sanfur in a completely opportunistic way. In film it is not easy to depict the dilemma that would have faced Razi by his duplicitous actions, but most certainly we the audience, contrary to Naaman’s opinion, are challenged to “contemplate the context of his actions and decisions”.

Waked states, “The viewpoint of the film is that of the Palestinians

themselves, whom we spent months interviewing in-depth, in order to write the screenplay. It is a very precise reflection of reality,” he

insists. “So if Gideon Levy doesn’t like what he saw in the film,

maybe it’s because he doesn’t like the reality.”

In fact, Waked regards the “failure to take an overt political stand”

as one of the film’s attributes. So much for Naaman’s desperate

yearning to see some footage about the occupation.

“Changing reality was not our goal,” Waked said. “But the film has

been viewed widely and is generating a debate in Israel. If it enables people to grasp that we are embroiled in a lose-lose situation that must change, then I would consider that an achievement.” Yet again Naaman missed the mark – the film does depict the reality of the conflict with a strong sense of realism. However it seems that she

didn’t get served the sort of reality that matches her biased

appetite.