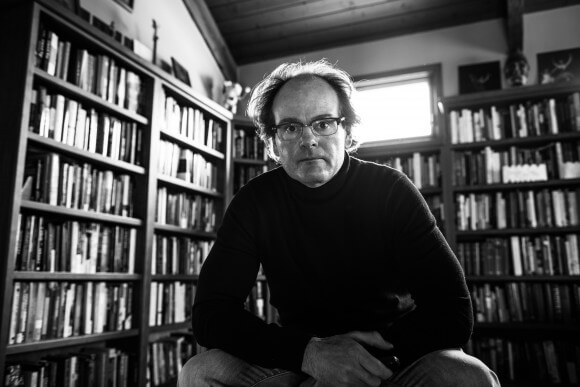

Leftwing critics have taken to describing Israel as a settler-colonial society, like Algeria under the French and South Africa under the Afrikaners, and they are having an impact. In the last year, both Jeff Halper of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions and Roger Cohen, the NY Times columnist, have warned that the conflict is beginning to resemble Algeria more than South Africa, meaning that the settlers will end up leaving. To understand the Algerian parallel, I sought out James D. Le Sueur, one of the leading American scholars of decolonization. Le Sueur is the author of Uncivil War: Intellectuals and Identity Politics during the Decolonization of Algeria and of Algeria since 1989: Between Democracy and Terror, and the editor of the war Journals of the Algerian writer Mouloud Feraoun. A history professor at the University of Nebraska, he is now writing a book about decolonization.

I interviewed Le Sueur by phone last September. It’s taken a little while to transcribe the dialogue, and Le Sueur added a few notes at the bottom. My questions are in italics.

Weiss: When people say that the Israel/Palestine conflict is looking more like Algeria than South Africa, they mean that the degree of contempt and radicalization is becoming so extreme that this will become a zero sum game, in which ultimately one side has to go. What do you think of the analogy generally?

James Le Sueur: While I appreciate the attempts to make comparison — in terms of how occupations or war radicalizes – I’d point out the very different nature of the French occupation of Algeria. It has a much longer history than the Israel-Palestine conflict. And after the beginning of the occupation of Algeria in the 1830’s and 1840’s, France almost immediately converted Algeria into three overseas provinces. That is very important because, in the French mind, when soldiers fought for the continuation of the French control in Algeria, they fought on French soil for France itself, and not in abstract terms. Hence the French stake in Algeria was a very significant feature of how the French became ever more imbedded in that conflict. As they said, “Algeria is France.” In the French mind, it was not a colony and what they did there was legally and entirely a French matter, and it continued to remain so all the way through the 1950s and into the early 1960s, as Algerian nationalists tried to bring the matter to the UN.

So very significantly, the creation of the state of Israel is a much more recent phenomenon, though the effects of occupation might appear to be the same. And Israel’s creation as a state also corresponded to the terrible events of the Second World War that were significant enough to allow American policymakers like Truman and other people (the British and the French) to side pretty firmly with the Zionists over and against the objections of the Arab world.

On the other hand the two histories, Algeria and Israel/Palestine, might be comparable because the violence continues to escalate in Israel/Palestine and has since Israel was created, because Palestinians view this as a colonial occupation. I have many friends who are on both sides of this issue, including liberal Jewish friends who oppose the continuation of the occupation. And on the ground, the settlements look a lot like French colonialism in some real ways. And the logic of the settlements looks a lot like the logic given by French settlers for ‘occupation’ of Algeria.

Tell me about radicalization.

These really violent colonial conflicts radicalize both sides. What happens though in the Algerian case especially– one of the greatest missteps in the whole French misadventure– is that the French settlers and the metropole government failed to seize any opportunities to mediate the conflict, or to compromise in an honest way, before it escalated. On this count, it seems similar to what has happened in Palestine, with all the missed opportunities for an honest compromise.

So, I would say that what happened in Algeria prior to the war of independence starting in 1954 is relevant for comparison with the contemporary and historical failures of the Israeli state and Israeli settlers to negotiate openly with Palestinians. The radical intransigence of the Israeli settlers is very similar to the more radical of the French settlers in Algeria. Ironically, in Algeria’s case, many 20th-century nationalists were not even calling for complete separation from France. Sure, they wanted equal rights, they wanted a number of things, but they didn’t necessarily demand complete independence from France. That idea of independence happens much later in Algeria.

After the Emir Abd el-Qadir is defeated in 1847, that idea of independence disappears for a long time. And it doesn’t really resurface till after the Second World War. And what happens in that period, from the late eighteen hundreds to say the nineteen teens or twenties, there were efforts on the part of Algerian nationalists to negotiate for more rights, for greater liberties and so on and so forth, but the Algerian colonial lobby in France refused to heed even these suggestions or listen to these necessary calls for reform.

Then another thing happens: In May 1945, you probably know, there’s a very violent crackdown on Algerian nationalists, for a couple of days in a region called Setif. The Setif massacre is really important, because up until that point the Algerian nationalists were calling publicly for the French to negotiate in terms of providing rights. After that crackdown, when the Algerians estimate that 45,000 people were basically massacred by the French military– that’s when the Algerian nationalists go underground, radicalize, and refuse to again ask publicly for the French to accommodate their demands for equal rights, etc. That’s where the radicalization of the nationalist movement happened, after the newly-liberated France massacred around 45,000 innocents, including women and children, just as Europe celebrated the defeat of Nazi Germany. After May 1945, the Algerians organize and collectively strategize about how they are going to pursue their agenda. Eventually, on November 1, 1954, the nationalists resurface with a revolutionary program. At that point, their goal is end the French ‘occupation.’ Though it remains unclear what the status of the Europeans there [roughly 1.2 million] would be.

In that context, the Algerian President Ferhat Abbas is a moderate, against the more violent FLN forces, right?

He was clearly part of the missed opportunity, and he is important as a moderate. He eventually gets sidestepped by the more radical factions of the FLN. But in the 1930s and 1940s, he was one of the people who looked to negotiate with the French, and he did hold important positions after he joined the FLN in 1956. And you know there’s a big debate about these people because most of them were not talking about complete independence from France.

The irony of this whole thing is that the idea of independence is first used by the French in Algeria who resent metropolitan France’s increasing encroachment on their way of life, their way of dealing with Algerians. So the French colons call for independence before the Algerians do. A similar phenomenon happens, of course, in South Africa. The Afrikaners resent the continued British efforts to suppress South African racism, and the Republic of South Africa is declared, which separates South Africa from British oversight.

This is a worldwide anti-colonial phenomenon. The settlers are trying to protect their discriminatory practices, and governments are trying to stop them. I know that in Israel that’s also part of the issue. Most people would agree that the more radical Jewish settlers, the ones who have built and who continue to build houses in illegal areas, they’re essentially colonial in outlook. In some ways, it reminds me of what happens before the American Revolution here. There were a lot of reasons of why the American Revolution happened, but part of it had to do with the resentment of American settlers when the British metropolitan officials told American settlers how to deal with Native Americans. American colonists didn’t like being told how to negotiate, how to deal with Native Americans, and which lands they could take from Native Americans as the settlers looked westward.

I see this debate about settlers as a pretty universal colonial question; it happens with all settler societies when they see themselves being surrounded by hostile forces and desirous of someone else’s land. And it’s tautological. Settlers need more military protection because they continue to make contested moves, and the more settlers there are, the more the military is needed to protect them. And as a result settlers have militaries that are bound to protect them and settler societies develop increasingly radical politics. So a government like Israel feels that contradiction of trying to protect settlers and at the same time rein them in because they’re considered even by most moderates in Israel to be pretty problematic.

But aren’t we past the age of colonialism? Wasn’t that what World War II was about? The frame is over? What is Israel in that context?

This is my take, having worked on this question within various archives in the US, Europe, South Asia and throughout Africa over the past 15 years. What happens, especially with Truman and Eisenhower, is the development of a deep philosophy that America has an obligation to support these emerging governments. This was also true of Israel. However, that support comes with a contradiction because Israel is viewed as colonial by the Arabs and many states. Israel behaved like a colonial state too, expanding its borders and developing a settler society/culture, etc. So it exhibits a behavior that appears to be in real terms colonial as its ‘nation-stateness’ begins.

It’s also ironical that these considerations take the US right into Vietnam/Indochina, to defend unstable regimes against so-called Communist imperialism. The US government made decisions in order to keep certain allies and to do certain things, even to support wars like Vietnam because of the logic of the Cold War. Israel benefited from that same logic.

It flips?

Yes. It flips. In Israel case, there’s a very understandable urge on the part of Europeans and Americans to help European Jews after the Holocaust. I think that is an honest and empathetic response. And then immediately there are problems because the British mandate officials find themselves in a bad security position during the war and from 1945 to 1947 in the territories. It’s similar to the British position in India in which the British military and security forces were facing the prospect of partition and civil war and they wanted to get out so as not to be trapped behind a colonial position when a civil war erupted. Consequently, Lord Mountbatten (viceroy of India in 1947) actually pushed forward the transfer of power by a year, moving it from 1948 to 1947 in order to clear his men out of the carnage that would beset India in 1947.

With the British Mandate in Palestine, the US seeks to avoid being drawn into these police and security questions.

Do you regard Israel as a settler colonial state to begin with? On the left people say that.

I think it was. It was settled by Zionists. Many of those settlers were refugees from Europe, and as the state emerged, it was connected to the experience of the persecution of Jews in Europe. Most people understand that. I also think that, getting back to the analogies to what happened in Algeria, like every state that emerges in a historical context, there are people who support that idea of the nation. In Israel that happens. In Algeria the same thing happens. That nation begins to crystallize and take shape, and the defense of that state takes on a life and a logic of its own. (We can’t forget the importance of the Arab wars with Israel, especially the 1967 war.)

And in that period in Algeria where people began to critique the French occupation there emerged a group of intellectuals who really were opponents of the French continuation and status quo in Algeria. And there’s a split among people in France. Some people supported the French colonization of Algeria. Others opposed the French status quo. Albert Camus comes to mind. He’s one of the people who grew up in the colonial context, he understands what it was to live in that world. He understands colonialism, but he doesn’t like it.

When we think about Camus and Algeria, we remember the famous line: between my mother and justice, between putting bombs on trams and supporting the people riding the trams, I choose my mother. Is it true his mother was a deaf and dumb person cleaning people’s houses in Algiers?

More or less, yes.

And he was saying the colons can be humble, working class. Not driving Cadillacs with cigars. But that must be true of all colonial situations.

I think one of the criticisms of the French anticolonial left– the French really have a different kind of anticolonialism. They were much more theoretical and much more public about it. Camus understood of course, being from Algeria, that not all colonists or settlers are the same, that all colons didn’t drive Cadillacs, smoke cigars, and drive around with whips, as he put it. Nor more importantly are all “Muslims” (the French term for Algerians at the time) the same. He knew that there were Algerians who were secular– the FLN itself was radically secular in fundamental ways, though it used Islam when it needed to, pragmatically. In key ways, the FLN mimicked the French left. They wore ties. They didn’t dress even like traditional Muslim leaders. Some people did. Not Messali Hadj, who represented a rival Algerian nationalist movement that was brutally liquidated by the fratricidal tactics of the FLN. But what Camus understood were the nuances. He also understood liberty and justice, freedom and so forth, and he connected those ideas to the democratic spirit of France. He’s a very sympathetic figure. Because he’s also an artist. He doesn’t swallow the bait of the left and shift blindly to Marxism or communism. He was critical of Marxism and critical of communism. Not only is he pushing back against the anticolonial spirit of France, but he’s also pushing against the bigger ideas, Marxism and communism, and he argued that they were ineffectual at fighting against colonialism. So he finds himself increasingly separated from the majority of intellectuals on the left.

In Camus, you have a very enlightened, very informed, very caring person who is trying to do the right thing in a world where it’s becoming increasingly difficult to be in the middle. It’s a polarized world, and the forces pulled in both directions, and pretty strongly. Camus really gets imbedded in ‘56 and ‘57 in the debate about Algeria when he starts to express reservations about the extreme violence of the FLN. Good for him, I think. Guess what– the FLN was pretty violent, even against its own people. The same was true for the French state, of course, which used torture routinely. But Camus understood the violence of the FLN, and he distrusted it. This is where I differ from a lot of historians. I do not shy away from writing about the brutal violence of the FLN. To be sure, the FLN represented the nation, but how did it get to this point? In most cases, it liquidated all of its opponents, even and most especially Algerian ones. The FLN’s postcolonial totalitarian nature (which still exist today) was formed in the fires of war against the French military, which used terrible and violent tactics to win Algeria at all costs.

You have written a lot about the Algerian intellectual Mouloud Feraoun, and the pity of Feraoun is that he said, I’m more French than the French, and French radicals kill him.

Yes, what’s really tragic about him is that he was killed by the rightwing pro-settler movement, the Organization of the Secret Army (OAS). Not the FLN. Whether he would have survived after 1962 is another question. I’m not sure he would have survived after the FLN took power. He may have been forced to go into exile. It’s impossible to say, but the FLN became a dictatorial totalitarian regime, period. It got into the mess in 1990s because it was that kind of brutal regime to begin with.

The tragedy of Mouloud Feraoun is that he, like Camus understood the effects of the violence on everybody, on both sides. And, like Camus, he tried to walk that middle line, and he was pretty effective. He did not like to be used by the French. In my mind he is one of the greatest figures of the 20th century, because he was simple, observant, brilliant, and honest. He was first and foremost a teacher. He stayed there on the ground, and stayed in the school, in one of the most violent wars in history. He has my sincere respect.

Could he have left?

Oh, sure, yes. He could have gone to France and taught in France. Many people asked him to do so.

I have a Spanish friend who works for the UN and when her friends ask, what’s the peaceful resolution of the Israel Palestine conflict?—she says, there is no peaceful resolution of the conflict. We’ve passed that point. When did Algeria pass that point? When did violence become the only way out? And once there’s violence, these figures in the middle are shredded. The OAS or the FLN might have killed Feraoun. Can you describe this arc of violence, when it’s too late?

When I look at the bigger picture, I think the missed opportunity in Algeria really came in 1945. Hitler is defeated, and Algerians go into the streets to celebrate VE day on May 8, 1945. They go into the streets with signs and slogans asking for greater freedoms, more civil rights. A scuffle ensues. Some Europeans and some Algerians die, and how did the French respond to these demonstrations in Setif? The Algerians are mowed down and massacred by the French military, as the French and the rest of Europe celebrate the defeat of Nazi Germany. That’s Setif in May 1945. The Algerians claimed 45,000 were murdered by the French in the wake of the Nazi defeat!

I think that’s where the whole game in Algeria changes. The leaders who were then asking for democratic changes, rights, basic freedoms, were above the ground. That is what they learned in that whole adventure a simply fact: being above ground doesn’t work, you need to go underground and use violence. I think the problem of violence is very simple: If people can complain and publicly militate for greater freedoms etc, above ground, then you’re in a place where peace is possible. If activists have to try to achieve their goals by being underground, as a guerrilla force or otherwise, it’s impossible in these settings.

In Israel, if both sides really want to resolve this, they need to get to a place where all opponents can be above ground. Without the threat of a state coming after them, or a movement coming after them. I think that’s one of the great lessons in history.

Presumably these lessons aren’t just discernible to eggheads at desks. But to leaders. Did Algeria play any role in the resolution of South Africa?

This is how I read South Africa. I just reread The Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela’s book. And I’ve spent a lot of time in South Africa, working in archives. And part of the genius of Mandela is understanding what happened to him while he was in prison, and the way he used his prison experience to not follow in the same historical footsteps that all the other decolonized countries followed. He had to step back. He said, I’m glad we were not immediately able to seize power in the 60’s because it might have led to an inferno. It’s a realization on Mandela’s part that by being in prison, he was able, South Africa and the ANC were able to re-think their relationships to Whites and Afrikaners — they still fought of course; a proxy war was under way on the borders– but liberation didn’t happen for the South Africans really until he took power in ‘94. So he had a feeling of being sidestepped by history. Ironically, he understood this may have been a strange blessing because he understood that if you come out and try to run these states like all these other states, like Zimbabwe, you have a revenge-oriented mindset. You have to find some way of moving the population, all races, together toward the same idea of the nation. That’s where the genius of Mandela really comes in. He learned from history. He’s one of the few leaders who actually did. He understood historically, that all these other nations came out with intense animosity, like Idi Amin in Uganda and so on, and went after all of the other people who they deemed oppressors. In South Africa, remember, in ‘94 we were all nervous about that possibility. I think the Afrikaners were pretty scared, so were the British descendants in South Africa, the blacks, as well — everybody was very nervous about what it meant to be South African. And one of the things that Mandela did was force the youth to back away from the revenge identity. Remember when he gets out of prison–I watched the videos again recently– they’re negotiating, they’re giving speeches, and those youth were really mad at him, because they didn’t think he was “radical” enough, he was some old curmudgeon who had sold out the revolution. He had to force those younger people back from that posture.

He had a base, though?

He had a base, sure, and he also understood that the international community was looking at him in a really specific way. And there were going to be punitive repercussions if he came out after all the whites who historically had been oppressing blacks.

In Algeria, who controlled events? Did extremists in French political culture control the events?

In July 1957, Kennedy, before he was elected president, gave probably one of the most important speeches he ever gave, and the speech was titled– and this is interesting considering what happens in the Bay of Pigs etc.– “Imperialism — the Enemy of Freedom.” And going back to your question, who controlled what, part of Kennedy’s argument is he wants the French to stop the war in Algeria. Kennedy tells them, Look, this is wrong, imperialism is really not working anymore as a way of being in the world, that kind of colonial world is gone. Part of his larger argument is, and this is really striking, he says something to the effect that there were 400,000 French soldiers in Algeria in a population that only has 1 million Europeans and 8 million Muslims. And I say Muslims because that’s just technically how France broke it up. Not practicing Muslims, but that’s the division that they had. So from Kennedy’s strategic point of view, those French troops were not positioned in Europe to fight against the Soviets, and in 1957, the Soviets were really a threat. So one of the things that Kennedy’s starting to articulate in American foreign policy is the desire to put a brake on these regimes that are oppressing people, and that means the French regime is oppressing people and refusing to recognize self-determination. But, let’s be clear, Kennedy’s eyes (and President Eisenhower’s as well) were on the defense of Europe, against Soviet imperialism in Europe. The Soviets weren’t bluffing, as Hungary in 1956 had just illustrated.

And other senators who replied to Kennedy, said, we need to stop funding France, they’re killing civilians in a war that’s not making sense any more.

So Muslims counted?

Yes. From an American perspective they did.

Now from the French point of view, they were fighting to maintain control over their territory. This is something that is often lost in historical translation, but it needs to be restated. French leaders, when they went to war in Algeria in 1954, were immediately supported by the Communist Party in France. One reason the Communists supported French rule is because they viewed it as siding with the European workers there, and the labor unions themselves in Algeria helped formulate the French reply. Eventually the Communists shift. But they’re completely pro-colonial in the first years. So the forces that buttressed French colonialism were very wide. They ranged from the left to the right.

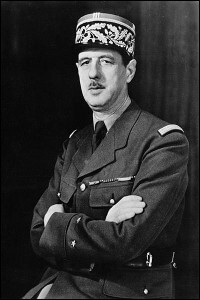

Is de Gaulle a man of vision?

I think that you can argue pretty clearly that de Gaulle is a man of vision. The debate is over what the vision was. He is also kind of like Mandela, if you will, in that he ended something his own way and in a way that he had come to only through direct experience with history. [Footnote 1] Remember, he had emerged during France’s darkest hours and in the humiliation of the defeat and the occupation of France by the Nazis. That said, he was never in favor of ending the French empire. Never, not even as he negotiate the peace in Algeria. Was he pro FLN? Absolutely not. Was he someone who liked to retreat? No way. He did it because he knew that France couldn’t survive economically or politically the continuation of this crisis that Algeria had become. He knew that continued war might destroy France.

Not only that. But there was substantial pushback because there had begun to be these really very serious protests and the anti-draft movement. There were people who rejected the draft and wouldn’t fight. And after the OAS emerged at the end of the war, it was impossible to maintain order in Algeria because the OAS began killing Algerians, French settlers, and the French military/police alike. The OAS were murderers and thugs, and they destroyed the last chances for the Europeans to remain in Algeria. [Footnote 2]

Ted Morgan’s book, My Battle of Algiers, gets at the issue of how the French in France also resisted the war in Algeria– they didn’t believe in the war.

Yes, many draftees frankly did not see the point of the war. But the true threat to de Gaulle was from the right, when the putsches started to happen. So de Gaulle had to stand up a couple of times before the cameras to ward off generals and soldiers who threatened to turn on him. Algeria was clearly bad for military morale. But the contradiction was that de Gaulle only got into power through a military coup himself, in ‘58. So he understood that military coups were possible because he himself had been the beneficiary of a military coup.

Remember in ‘58 it got so bad that de Gaulle was put in power by the French military under the threat that if de Gaulle didn’t take power, France was going to be attacked by the French military from Algeria. That’s the threat the French generals made, and they meant it: put de Gaulle in power or else we’ll take France from Algeria.

Did the French military not understand the consequences?

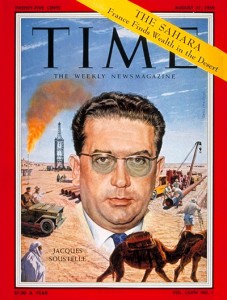

They were thinking that de Gaulle would be the only person who had the moral strength to keep Algeria French. That’s where the deception from their point of view comes in and that’s what makes Jacques Soustelle so interesting. Because there you have a politician from the extreme left who gets sucked into the settler colonial world, and gets spat out the other side of the colonial vortex on the extreme right, to the point where after de Gaulle announced that he will abandon Algeria, as a territory, one of the people who openly supported the assassination of de Gaulle is Soustelle, who had helped put de Gaulle in power in ‘58.

Jacques Soustelle was the governor general of Algeria from 1955 to 1956 and he created the educational institution that Mouloud Feraoun eventually taught in. And people like Soustelle represent just that force of gravity that the extreme right has on settler and colonial politics. He was very educated and very politically savvy. He was an anthropologist sympathetic with the indigenous movements. He co-founded the antifascist movement in France in 1936 and then becomes, by most people’s accounts, a fascist by the end of the Algerian war.

That’s what Algeria was for France. It has the capacity to force some of the most personal reversals in positions. It chewed intellectual-politicians like Soustelle up.

The socialists who founded Israel could look in the mirror and say I’m Soustelle.

Right. You see the same kinds of flips. It’s part of how settler politics transformed people in extreme ways.

But you’re saying the French right wing made a wager that was a bad wager; it was a misjudgment and it was on the quote unquote wrong side of history, with disastrous consequences, in that Derrida’s family, which had lived there for hundreds of years– they were essentially expelled, with 1 million other French.

They chose to leave.

Did any stay?

Some people like Henri Alleg, who was also Jewish– remember he wrote The Question— he went back to Algeria after ‘62. There were people who went to Algeria after ‘62. So, I’m saying that it was a choice to leave Algeria. Algerians gave them the choice of staying but only if they would accept Algerian citizenship. They had to become Algerian by nationality. And for whatever reason Derrida’s family didn’t think that that was something they wanted to do. There were real safety concerns for Europeans and Jews after the war, just as there were safety concerns for the Harkis and Algeria “collaborators” with the French after the war. Algerians engaged in a lot of revenge killings at the end of the war.

Benoit Peeters’s biography of Derrida said the family were unsafe.

Yes, they believed they were unsafe. I don’t know if they were unsafe. It is certain that many were not safe in Algeria in 1962.

Were there massacres?

Some of the people who were being massacred in ’62 were the people leaving Algeria. Remember that the OAS was out there killing people, especially those trying to leave. The FLN supporters also killed many. Killing and violence had become the norm, it had become normalized by the war. This is awful stuff.

What about the words, the suitcase or the coffin?

That was for the colonists. This is the era of marketing and slogans. That’s how you market a revolution.

Some slogans are accurate.

But they were not killing all the Europeans. In fact, the French cooperation after the war is really strong. I have known a lot of people who went back to teach. Etienne Balibar, a really famous French sociologist, he went back to teach at the University of Algiers. They had a whole lot of economic and cultural cooperation in the immediate postcolonial period, particularly in the fields of education and in the oil sectors.

OK, so no expulsion. But, a dream of coexistence ends, right?

I think the reason that 1 million people left is because they considered themselves French. The Algerians said they could stay, they just had to have Algerian nationality. And so the panic– it’s a legitimate panic, right? The FLN had hideous practices of decapitating people, cutting their noses off and stuff like that– that didn’t really bode well if you want to try to convince people to stay in your country after independence, when this has been happening to settlers and Algerians alike. Farmers and settlers were routinely killed by the FLN; they were viewed as part of the occupation. I’d point out that you have large numbers of Algerians who died at the hands of Algerians. That’s something the Algerian government hates to talk about. Revenge killings are a major part of this war, but so was the French violence against Algerians. The French committed what we would call war crimes on a daily basis. Disappearing gets invented here, and then the French start teaching torture and counter-insurgency throughout Latin American and even to Americans at Fort Bragg in the late 1950s.

If Mandela wanted to avert the outcome of Algeria, what is it that he averted?

Part of the thing that South Africa benefited from was not achieving independence as quickly as other countries. I know it’s not politically correct to say this, of course, and it’s not my idea. It’s something Mandela himself came to accept. Mandela understood that South Africans had to emerge from apartheid and at the same time avoid become dictators. Look at the rest of postcolonial Africa. It’s not a good story. It’s not even a good story in Algeria, is it? The historical insight that Mandela takes away from is that, in prison on Robben Island, he saw much of Africa go up in flames and he learned that violence must end, first and foremost and that people must admit their mistakes, openly and publicly and that history has to be used to build not destroy a nation. He learned that identity politics are a nasty business if accompanied by violence.

Algeria had had a sustained war that radicalized and brutalized and created a great divide, and broke the bonds, for seven years or so. True? Am I wrong in saying that didn’t happen in South Africa?

I think you could say that South Africa had a low grade war longer than Algeria did. It had pretty excessive violence. And the ANC took the war to the border states because they could get funding from other governments, including the USSR and Cuba and other proxy governments that were involved. So they had guerrilla movements on the periphery of South Africa that continued the “anticolonial” war longer than Algeria’s. But there wasn’t the kind of intense killing that happened in Algeria, or even the killing of Algerians by Algerians. To be sure, there was killing and extreme violence in South Africa. Mandela himself was arrested, in part, for openly advocating political violence, but the scale of it in Algeria was surreal. The idea of the nation that emerges in Algeria is really interesting because that nation emerges in a context where there are upward of hundreds of thousands of French troops fighting against them, and the French–let’s be honest–these were pretty brutal forces. Torture was routine, it wasn’t just every once in a while. It became banal for the French, just part of the war. There were no polite discussions of waterboarding. It was full-out torture. It became a fundamental part of the military response to the Algerian revolution.

Again, to deescalate this, the way to go forward is you have to have people not fearing that speaking openly and demonstrating openly will cause them harm. The same kind of lesson happens in 1968 in Czechoslovakia. The people go into the streets, the Vaclav Havel types, they think that the world is going to side with them because it’s the right thing for the world community to do, that the world won’t let this moment pass them by. And they’re wrong. Just kind of like the debate about Syria that is happening right now.

But in Egypt, they went into Tahrir and the world actually supported them, the media did, and Mubarak collapsed.

But the military just sat there and waited it out. The Egyptian military, it’s pretty clear to me, had a strategy of how to do this. They were going to let democracy start, pretend that it was real, and the moment the democracy emerged with images that contradicted the military, it was shut down. Egypt just followed the tactics that the Algerian military did in the 1990s there to a letter. Egypt is still completely under the thumb of the military. It’s clearly not a good time for freedom there.

If my goal were to preserve the Jewish population in Israel– there are 6 million Jews in Israel/Palestine and I personally want a one-state democracy– how do I do that? What should I be telling Israel to do?

I’d go back to the moment that Kennedy gave his speech that I mentioned in July 1957. It’s a moment when things are still possible [in Algeria]. And so you’d have to ask is it possible to have Arabs and Jews living together in one state. You have to give equal political weight to all the given elements. Right? One vote is one vote, and people have to have the right. Let’s say that there are X number of non-Jewish people in that territory. Then the politics has to be real, it has to represent the voice of those people. There is no way forward until the justifications for violence are put aside and until compromise is reached, and until it is real.

Were there discussions of partition in Algeria?

Yes. Some settlers suggested separating the colonial coastal towns from the rest of Algeria. There were discussions about this. But I don’t think it was ever that significant a discussion. One of the debates, though– and this is where Soustelle comes back into it, by the mid 1950s, oil was discovered in the Sahara, and the growing concern for the French was to keep those oil reserves along with it’s nuclear testing sites in Algeria. And Soustelle even wrote a pamphlet to that effect, about the Sahara as a strategic possession that must be maintained by France. In fact, those parts were considered legally separate during the French Algerian war, because they were specifically related to energy and security. They were part of the energy structure.

So both sides honored that?

Well, the Algerians didn’t have a say in it until later, but in the Evian accords, these issues are a big part of the negotiations that eventually brought about the cease-fire in March 1962.

I read in Algerian Chronicles, by Camus, ’58, he says this country can’t be torn apart, a reference to partition.

Camus wants to have a notion of federation. There was a strong movement of people who had supported federation. But again, in ‘45 federation was probably impossible, not after that kind of war.

Why does that mean, federation is not possible?

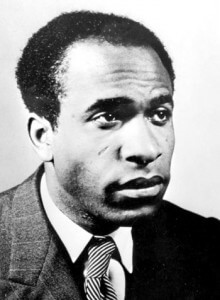

It’s not a realistic goal because the violence had escalated to such a degree. And remember that by ‘57, ‘58 there were theoreticians of violence, like Frantz Fanon. And they had not only a political idea of it, but a philosophical idea of the utility of violence. And this is one of the criticisms I have with people like Fanon, who was an unbelievably brilliant person but somewhat irresponsible. I’m alone here; there just isn’t a very critical understanding of the negative effect of people like Fanon on Algerian nationalism. But if you have nationalists advocating that kind of extreme violence, and it sounds really logical as a piece of literature, putting it into practice is quite another thing. And then developing a national idea and the hegemonic state that comes out of that–it’s not an accident to me that Algeria took the course it did. Now, of course, Fanon didn’t create any of this. He was merely writing about it. Nevertheless, he was a significant figure, and the fact is that it’s really hard to stop violence, especially if you have a theoretical justification of it that gets really embraced by the FLN and then celebrated by the likes of intellectuals like Jean-Paul Sartre. It’s almost delusional what happens, if you really look at the words: killing a settler and a European is like killing two birds with one stone [as Sartre wrote in the Preface to The Wretched of the Earth]…

If an Israeli wants to avert war by changing that society– when is it possible? When do folks still have the ability to make foundational change?

The bottom line is, is if you want coexistence, you have to stop justifying violence. Period. Each side must have the courage to stop using violence. Where has violence gotten either side? Is it really something worth defending, this life of violence? I know this sounds simplistic, but leaders need to be found who have the courage to end this violence. Both sides. And if it’s your side that’s doing it, you have to have the courage to say it’s excessive. That’s why Camus is so important. He said, the violence on both sides was excessive, and he berated the French politicians for acting like imbeciles, he denounced racism in Algeria, and he denounced the “terrorism” of the FLN. He could do this because he understood the country and had command of its issues.

But at that point, he was politically irrelevant?

Well kind of—but he was well respected. He’s still the most widely-read French author in the world. [Footnote 3]

If you look at the American Civil War, John Brown who was a brilliant madman and idealist, said that this institution, slavery, will only be removed by “verry much blood,” in the 1850s, when the politicians were doing nothing to remove it, and he controlled events more than anyone else.

Yes, the Civil War is a good example of how sometimes violence is necessary. But when does violence end?

It eliminated slavery in the US, at the cost of 700,000 lives.

I’m not saying in America. I’m saying in Israel. Has the violence in Israel achieved whatever goals there were, those who argued in favor of the violence? Either on the Palestinian side or the Israeli side, what has violence achieved? Maybe if you had a basic simple, just a very simple and honest answer to that, you would have some way to move forward. Now, of course, I know about the Arab wars about Israel, and I understand and appreciate how these wars changed the debates in Israel about security.

I would say that Palestinians have absorbed that lesson by and large and they are involved in a nonviolent struggle. They care about world opinion. But Israelis would say our violence is necessary because we’re surrounded. So they have created out of fear for their security, a Sparta state. It’s a great question you raised and that’s the answer.

The problem for Israel is, I think, the legitimate concern about people like Ahmadinejad, lunatics who want Israel wiped off the map. That’s a serious concern because it represents a state now making threats against another state. Israeli politics can’t really be fully addressed till you think about these other actors out there, and think about these lunatics like Ahmadinejad. At the same time, I think it’s clear that Israel has pretty strong supporters, and as far as I can see the US position on Israel is not going to go away.

Couldn’t you say the same thing about France? They would never abandon Algeria. Today even John Kerry says that the status quo in Israel and Palestine is unsustainable, and privately god knows what American leaders say. But meantime Israelis will say, The US will always be behind us. I imagine there were French intellectuals and colons saying the same thing back then?

I guess what I would say is, we can’t control how other states are going to view Israel. That’s pretty obvious. Saudi Arabia, these other states, they’ll always have a pretty hostile view of Israel, and I don’t know how and if that can be dealt with. Now if the Saudis become a threat, that’s a different thing. Especially Iran. But with regard to the Palestinian question, the immediate question, how you bring reconciliation forward— it sounds naïve, but fundamentally, you have to have people like Mouloud Feraoun out there, teaching about how you live and coexist with each other. At a fundamental level, if you don’t respect the identity and the dignity of another human being who’s on the other side, there’s no way to move forward.

To end on a kind of Voltairean note, I say we have to get to the point where we can say that don’t agree with you but I support your right to disagree. You need to have more Voltaires out there brave enough to meet disagreement with a firm and friendly handshake.

Le Sueur wished to add these historical notes to his comments:

Note 1. De Gaulle of course was not like Mandela in a lot of ways, but the analogy is useful inasmuch as de Gaulle looked for peace and brought France along with him through a very painful process. here are similar in that they were both considered criminals by their governments and a both fought from the ‘margins’ to liberate their nations from oppressors. De Gaulle was even condemned to death for treason by the Vichy regime. Both were on ‘the right side of history,’ as it were. However, their positions on colonialism and imperialism could not have been further apart.

Note 2. In fact, it is widely accepted that had not the OAS emerged in the last two years of the war, the French in Algeria may have been able to stay there in some negotiated settlement. It was the fascist violence of the OAS that ended the French settlers’ chances of remaining in postcolonial peaceful Algeria. And, as I wrote about in the publication history of Assassination! July 14 by Ben Abro, the OAS nearly killed de Gaulle in its assassination attempts.

Note 3. As to Camus’s relevance, I’d say after 1957 he was compromised by the misquoting of him done by Le Monde’s reporter covering his Nobel Prize visit to Sweden. And by 1958, for sure, he felt very isolated from the rest of the anticolonial movement in France. Ironically, of course, I view him as purely anticolonial from the beginning to the end, just not how Sartre or Fanon defined anticolonialism. I have an article on Camus’ anticolonialism coming out in a special issue of the South Central Review edited by the great Camus scholar Robert Zaretsky, in fall 2014.

Very good. I had some disagreements towards the end, when he spoke about the Saudis and the Iranian “lunatics”–it seems to me that he’s fallen into some cliches there.

But on his own specialty, Algeria, and the lessons he draws, I agree. Algeria was not a success story–it was case where everyone lost. This is ultimately the fault of the French–their extreme violence created the extreme violence of the FLN, but all the same, the victory of the FLN is nothing to be celebrated. They “won”, and a homegrown dictatorship replaced the French dictatorship. Then they had another brutal civil war in the 90’s.

It’s why nonviolence is the path that gives the best chance of reaching a just solution. Of course, those who oppose BDS are in no position to make that point.

Very encouraging critique of Israel by the US negotiating team – Obama is determined to solve this peace fiasco. This is a landmark of huge proportions.

http://www.timesofisrael.com/us-officials-even-if-israel-doesnt-like-it-palestinians-will-get-state/?utm_source=The+Times+of+Israel+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=c2be1a8301-2014_05_03&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_adb46cec92-c2be1a8301-54626049

ok, Phil, you’ve brought el Cheapo to her knees. Donation on its’ way to Mondoweiss as soon as I figure out how to do it. Great interview. Brilliant choice. And you asked all the right questions.

Pressed by Barnea on perceived international hypocrisy over Israel’s presence in the West Bank, when the world “closes its eyes to China’s takeover of Tibet, it stutters at what Russia’s doing to Ukraine,” the Americans were quoted as responding: ”Israel is not China. It was founded by a UN resolution. Its prosperity depends on the way it is viewed by the international community.”

Perfect.

Le Sueur probably would have had a lot more to say about the uprising in Algeria and the OAS’ failed putsch in France and on the army’s torture of Henri Alleg, his book describing it, J-P. Sartre’s involvement in it and Camus’ shying away from it. But Phil was basically interested in Israel’s colonization and occupation and was looking for parallels with the Algerian situation and for solutions to the problem with the Palestinians and Le Sueur politely went along but the expense of not going into the more interesting details of the story of the uprising.