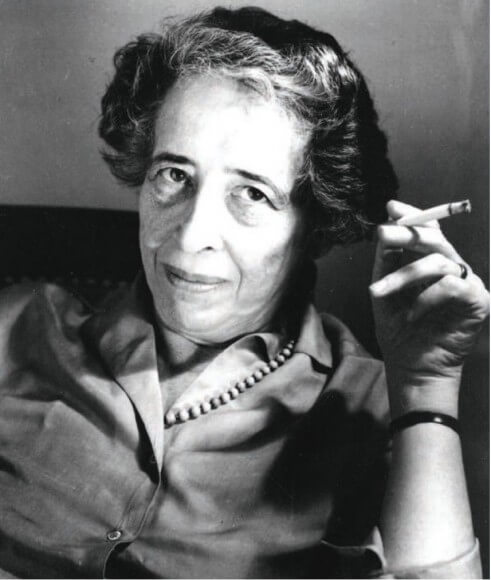

Corey Robin has a deeply interesting article in the June 1, 2015 edition of The Nation wherein he wrestles with the issues first raised 52 years ago by the publication of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem. I’ve been chewing on it like a dog on a bone the last few days.

What is it about Arendt’s reportage of the Eichmann trial that still draws fireworks today?

Eichmann and the Holocaust

Adolf Eichmann was born in Solingen, Germany, on March 19, 1906. During World War I his family moved to Linz, Austria. Hitler, too, had spent student years in Linz; as had Wittgenstein. Adolf Eichmann was the only one of five sibilings who failed to complete high school or vocational school.

Eichmann joined the Austrian Nazi Party in April 1932, and by that November he joined Heinrich Himmler’s SS, the paramilitary force that provided security at Nazi meetings and rallies in Linz. Having lost his salesman job for an American oil company in early 1933, and the Nazi Party being banned in Austria, Eichmann left for Germany. There he attended a several-week SS training camp.

The first anti-Jewish laws were passed in Germany in 1933 amid escalating violence: Jews were barred from the Civil Service and all government employment. Extra-judicial arrest powers of the state, first instituted after World War I, were expanded and appropriated by the Nazi party, permitting the Party to arbitrarily arrest anyone and detain them in concentration camps with no court oversight. Hannah Arendt, who was gathering evidence of Nazi anti-Semitism, was also briefly arrested and imprisoned by the Gestapo in 1933. She was later detained a second time in occupied France as an enemy alien by the Vichy regime, before managing to make her way to New York.

At the Sixth Party Congress in 1934 Hitler proclaimed that from the beginning, the goal of National Socialism was to be the sole political force in Germany. “The aim must be [for] all Germans [to] become National Socialists,” he said. Rudolf Hess, the deputy party leader put it this way: “Thanks to your leadership,” he said, addressing Hitler, “Germany will achieve its goal, to be a Homeland … for all Germans of the world.” [See Reifenstahl’s Will to Power @24:00] A Nazi ruled homeland for racially pure Germans …. and no others.

In a police state, they say, the worst elements rise to the top. Eichmann proved to be a successful striver in this system. Between 1933 and 1939, through violence, economic pressure, deprivation of citizenship, and discriminatory laws, Germany encouraged Jews to emigrate. The Nuremberg Race Laws were enacted in September 1935, depriving Jews of German citizenship. Of the approximately 437,000-522,000 German Jews in Germany in 1933, approximately 250,000 had left by the outbreak of war. [160,000 to 180,000 German Jews were killed during the war; by 1950 approximately 37,000 Jews remained in Germany]

In 1937 Eichmann traveled with a delegation to British Mandatory Palestine to assess Palestine as a possible destination for Jewish emigration from Western Europe. Nothing came of this. After the Anschluss of Austria by Germany in March 1938, Eichmann was posted in Vienna to encourage and facilitate Jewish emigration from Austria. In 18 months, Eichmann’s organization processed 180,000 emigrating Jews from Austria. My wife’s family was touched by this. My mother-in-law, who lived in Vienna with her family, was expelled from school and subsequently sent to live with a family in Britain. Her brother was sent to Holland in preparation to go to Palestine, but found his way to New York instead; her father was humiliated and forced to clean the sidewalk with a toothbrush by SA thugs–he emigrated to Shanghai by boat from Italy; and her mother flew to New York from Belgium shortly before the outbreak of war.

With the outbreak of war all emigration stopped. By late 1941 the Nazi policy shifted from forced deportation to extermination. On January 20, 1942 the head of the SS secret service, Reinhard Heydrich, assembled the heads of the various German civil and war departments at Wannsee in Berlin to discuss implementation of the Final Solution. In the Mandel/Pierson film dramatization of the conference starring Kenneth Branagh (favorably reviewed by historians), Eichmann sits to Heydrich’s right. Eichmann issued a memorandum memorializing the meeting in euphemistic, but unmistakable language. (Unfortunately the film is now under a paywall, but you can get the gist of it here) At the Wannsee conference Auschwitz is identified as the primary killing center for the Holocaust in Western Europe. Construction on the gas chambers and crematorium began in October 1941. By March 1942, a never ending stream of trains transported victims from all over Europe.

|

| In March 1942 trains began arriving daily. |

Between 1.3 to 1.5 million were murdered at Auschwitz. More than 90% of the victims were Jews. Throughout the war, Eichmann was in charge of logistics for coordinating and transporting Jews to concentration camps. In addition to Auschwitz, 450,000+ were killed at Belzec, 200,000 at Sobibor, 700,000 to 900,000 at Treblinka, 60,000 in Minsk, and 152,000 in Chelmno. These Polish camps accounted for approximately 50% of the Holocaust victims, with the rest taking place in the killing fields further East (outside Eichmann’s jurisdiction).

After the war, Eichmann lived under two assumed names in Germany until 1950, at which point he was helped by sympathizers to obtain a Red Cross humanitarian passport and entry papers to Argentina. His family joined him in Buenos Aires in 1952, and Eichmann found employment at Mercedes-Benz, rising to department head. In May 1960 Eichmann was captured by Israeli Mossad agents and brought to Jerusalem for his reckoning.

Eichmann in Jerusalem

In his testimony throughout the trial, Eichmann insisted he had no choice but to follow orders, as he was bound by an oath of loyalty—the same superior orders defence used by some defendants in the 1945–1946 Nuremberg trials. Eichmann asserted that the decisions had been made not by him, but by Müller, Heydrich, Himmler, and ultimately Hitler. [Robert] Servatius [Eichmann’s German attorney, paid for by Israel] also proposed that decisions of the Nazi government were acts of state and therefore not subject to normal judicial proceedings. Regarding the Wannsee Conference, Eichmann stated that he felt a sense of satisfaction and relief at its conclusion. As a clear decision to exterminate had been made by his superiors, the matter was out of his hands; he felt absolved of any guilt. On the last day of the examination, he stated that he was guilty of arranging the transports, but he did not feel guilty for the consequences.

The judges reached a verdict on December 12, 1961. They entered findings that Eichmann did not personally kill anyone, that he was responsible for the dreadful conditions on board the deportation trains, and that he was instrumental in obtaining Jews to fill those trains. The Judgment found him guilty of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crimes against Poles, Slovenes and Gypsies. He was also found guilty of membership in three organizations that had been deemed criminal at the Nuremberg trials: the Gestapo, the SD intelligence agency, and the SS.

The second criticism, that Arendt underestimated Eichmann’s extreme anti-Semitic hatred, and that she was wrong to call Eichmann’s evil “banal,” remains very active to this day. I direct you to Corey Robin’s comprehensive article for the details.

If it can be shown that anti-Semitism was not present at the nadir of Jewish history, what justification can there be for a Jewish state today? Hence attacks on Arendt for a claim she never made.

That’s a provocative question, and Robin does not develop it: does the justification of a Jewish state require the existence of anti-Semitism?

There is, of course, considerable attachment to the notion of the existence of anti-Semitism in the Jewish community. Netanyahu uses it to convince French Jews to move to Israel; American philanthropic and political organizations use it to raise money. Netanyahu uses it to fight any lifting of sanctions on Iran. Israel uses it (“the Arabs all hate us and want to push us into the sea”) in order to maintain the occupation. All of these are tainted with motive; a claim of anti-Semitism is convenient for these causes.

Which is not to say that anti-Semitism does not exist. But if anti-Semitism is not an existential threat to Israel or Jews in the Diaspora today, or ceases to become an existential threat in future, does this undermine the justification for a Jewish state? Is an ethnic state by and for Jews, with a sizable Palestinian minority, a viable thing in a world without anti-Semitism?

Which brings Corey Robin to the religious heart of his article. Eichmann’s real moral failing, which is beside the point for his guilt or innocence, but which made him such a dangerous man, said Arendt, was his inability to empathize, to imagine himself in the shoes of the other and to take that into account–really take it into account as he goes about his actions.

People objected because they did not want to be judged. They did not want to be judged for their actions during the Holocaust, and they instinctively feel that a virulent anti-Semitism inoculates Israel against criticism for its actions.

What would it mean for Netanyahu and his government to empathize with Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank: to really put themselves into their shoes. Evil is thought-defying, wrote Arendt in a letter, because “it can overgrow and lay waste the whole world precisely because it spreads like fungus on the surface.” In other words, says Robin, Arendt was raising old Jewish demands of mindfulness about life, the knowledge that it is our smallest actions of which heaven and hell are forged.

What she was really being criticized for, suggests Robin, is “The intransigence of her ethic of everyday life, her insistence that every action matters, that we tend to the minutes of our practice–not the purity of our souls but the justness of our conduct and how it will affect things; if not now, when all is hopeless, then in future, when all will be remembered.”

Robin quotes from Arendt’s famous letter to Gershom Scholem:

Let me tell you of a conversation [with Golda Meir] about the disastrous non-separation of church and state in Israel. [She] said: “As a socialist, I, of course, do not believe in God; I believe in the Jewish people.” I found this a shocking statement and, being too shocked, I did not reply at the time. But I could have answered: The greatness of this people was once that it believed in God, and believed in him in such a way that its trust and love towards Him was greater than its fear. And now this people believes only in itself? What good can come of that?

What good indeed.

This post first appeared on Roland Nikles’s site two days ago under a slightly different headline.

Interesting how you left out the Sassen interviews, the tapes of which still survive. In them, Eichmann brags that he was not simply taking orders but actually that he was a “thinking” member who helped to plan the extermination, claiming he was an idealist.

It’s also interesting how you equate decisions that had at least direct and significant strategic (denying an enemy sanctuary by displacing and demolishing villages of enemy sympathizers) and tactical (clearing villages in Operation Nachshon (including Deir Yassin) to halt enemy raids against vital convoys traveling along the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem coastal road) impact on the conduct and success of the Jews in the Palestine civil war (where hostilities were begun by the Arab side under Abdel Qadr al Husseini, a man with the dubious honor of being recognized for his mutilation of his enemies) with the deliberate, gratuitous, unprovoked, and militarily counterproductive expulsion and later mass-murder of the Jews in and around territory occupied or annexed by Germany.

At worst, you could compare it instead with the clearly worse behavior of Czechoslovakia in 1945 regarding the disposition of the Sudeten German population as well as the Benes decrees declaring the seized property of those expelled as reparations for a war brought on by that population. But then, I don’t expect Mondoweiss or her commenters to have the integrity or consistency to condemn the Czechs with anything resembling the force or frequency of her condemnation of Israel.

I happen to be bothered by neither case.

I think it is apposite to quote Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s letter to his subordinate during the Vicksburg campaign:

“If they want eternal war, well and good; we accept the issue, and will dispossess them and put our friends in their place. I know thousands and millions of good people who at simple notice would come to North Alabama and accept the elegant houses and plantations there. If the people of Huntsville think different, let them persist in war three years longer, and then they will not be consulted. Three years ago by a little reflection and patience they could have had a hundred years of peace and prosperity, but they preferred war; very well. Last year they could have saved their slaves, but now it is too late.

All the powers of earth cannot restore to them their slaves, any more than their dead grandfathers. Next year their lands will be taken, for in war we can take them, and rightfully, too, and in another year they may beg in vain for their lives. ”

But that is war.

“Down-playing the role of anti-Semitism presents “a dire and existential threat to Jewish well-being,” says Deborah Lipstadt (according to Robin).”

Perceived anti-Semitism is the mother’s milk of Zionism. It is the ideological glue which defines, unites and motivates Jewish tribalism, keeping Zionist Jews psychologically separate from the surrounding Gentile communities. It is this Jewish kinship which is a key component of organized Jewish Zionist power-seeking and Jewish Zionist material success. Zionism is the modern, secular equivalent of Classical Judaism. Apparently Deborah Lipstadt feels that this tribal unity is essential to Jewish well-being (power) and that the lack of tribal feelings of kinship due to lack of fear of anti-Semitism would result in Jews simply becoming part of the surrounding Gentile community instead of psychologically remaining a people that chooses to regard Gentiles as irrational Jew-haters would constitute “a dire and existential threat to Jewish well-being.” She is probably correct.

The term ‘Polish camps’ is incorrect. The German Nazis established the ‘ camps’ on occupied Polish soil. The camps were not Polish as implied by the comment. Please correct the error.

It’s inteded as “camps in Poland.” Thanks jimpers.

RE: Rudolf Hess, the deputy party leader put it this way: “Thanks to your leadership,” he said, addressing Hitler, “Germany will achieve its goal, to be a Homeland … for all Germans of the world.” ~ Roland Nickles

SEE: Why “Homeland”?, by Thom Hartmann [VIDEO, 09:18]

Published on Sep 24, 2014

Thom Hartmann explains the origins of the term “homeland” and why he doesn’t like it being used to describe the United States.

LINK [VIDEO, 09:18] – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OCSwNW-axM0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OCSwNW-axM0