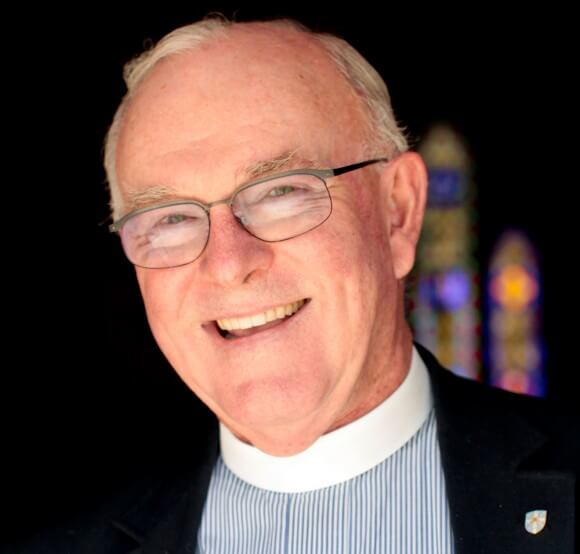

A year ago yesterday The New York Times published the famous three-sentence letter by the Rev. Bruce Shipman that ended his career as Episcopal chaplain at Yale. Responding to a Times report on growing anti-Semitism in Europe, Shipman said some of that hatred was fostered by Israeli policies, including the “carnage” in Gaza and the occupation.

As hope for a two-state solution fades and Palestinian casualties continue to mount, the best antidote to anti-Semitism would be for Israel’s patrons abroad to press the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for final-status resolution to the Palestinian question.

The uproar that followed involved even the president of Yale (who had just given a big talk on free speech). Shipman was compelled to resign his chaplaincy; and many Jewish publications scolded him for the suggestion that Israel was to blame. The Center for Jewish Life at Yale held a special conference about anti-Semitism that seemed designed to kick Shipman down the stairs again.

But this summer, several Jewish sources have echoed Shipman’s meaning.

First, here is Abe Foxman writing in the Washington Post July 10, With Jews’ Power Comes Responsibility:

What share of what Israel does justifies criticism, and what share does not, are subject to interpretation and consideration. But part of the discussion must always be: What can Israel do, what does it need to do better, how can its actions have an impact, not on the haters who will always be there but on the many non-anti-Semites who are troubled by some of its policies?

The temptation to reject such thinking as blaming the victim should be resisted. We are not living in an age of fantasists, though plenty of fantasists are still around. We are proud that Jews have a modicum of power, and we should act accordingly.

The rejection of this approach undermines the ability to deal with the real anti-Semitism that exists.

And it prevents what is needed both in the community and in Israel: a serious conversation about not only how to combat our enemies but also what we need to do to make things better and to weaken the fertile environment in which the enemies of Israel plant their poisonous seeds.

Then in July the Jewish People Policy Institute released its latest report on world Jewry. The report said that Israel’s actions can cause “difficulties” for Jews in western societies.

Following up the report, the rightwing site Arutz Sheva said “rising anti-Semitism” has made the relationship between Israel and western Jews “even more complicated.”

“On the one hand, it caused Israel’s role as a shelter for persecuted Jews to stand out, yet on the other hand, it sharpened questions concerning the connection between Israel’s policy and attacks against Jews all over the world and as to its role as the representative of Jews who are not its citizens.”

JJ Goldberg filled in the picture of the report in the Forward:

During a roundtable discussion the institute held near New York with local Jewish community leaders, “most said that Israel’s actions during war cause them to be ‘prouder’ of Israel,” the report says. But “when asked to characterize how they thought ‘other Jews in the community’ felt in the same regard, a higher proportion also identified feelings of ‘detached,’ and even ‘embarrassed.’”

Far more alarming, the report says that Israel’s wars have a strong, direct impact on the relationships of Diaspora Jews to their surrounding communities and societies. Mainstream Jewish community leaders in several countries told the institute that there is an “automatic tendency” for the surrounding non-Jewish society to “view Jews as representatives of the pro-Israel position.”

This has the direct result — as the institute initially noted last year, the current report points out — of “increasing the frequency and severity of harassment/attacks on Jews in various places around the world.”

“This insight was particularly emphasized this year in light of the bloody incidents in the Jewish community of France,” the report says. It quotes a Jewish community leader from France saying: “Every time [Israel uses force] synagogues are burned.”…….

Drawing a causal link between European anti-Semitism and Israeli behavior — between any anti-Semitism and any Jewish behavior, for that matter — is taboo in current Jewish discourse, to the point that suggesting it is itself treated frequently as an anti-Semitic act. It must have been frightening for scholars operating in this environment to stumble across first-hand testimony that the link is real.

The fact that so many Jews can address this question without any career damage, and it’s kryptonite for a non-Jewish clergyman (of considerable experience and gravity) is a sad reflection on the American discourse. In fact, it’s a form of ethnic discrimination. And it’s unfair. It’s one thing if only members of a persecuted minority get to comment on that minority; I understand that ancient prohibition. But when you have power– a lot, I say; or a “modicum of power,” as Foxman says — then you should be able to take some criticism.

I don’t regard Shipman’s comment as a criticism (though Israel deserves that, and he should be able to give it) but as a statement of fact, and sound advice.

Phil,

If the first part is true, that the truth matters more than the source, and I think I agree, than your second part is not morally consistent, imo. I think this is important to you as a kind of Jewish exemption, a way out of a particular kind of community pressure, to be sure )which as you know I support), but also a way around liberal conventions you will still apply generally to other groups, especially those with whom you have empathy.

In fact, groups can be powerful and not in different times and places and even in the same time and place. In the Jewish example, from the myths, Esther and Exodus both depend on this combination.

Shipman is either right or not, as he might be opining about Palestinians or African Americans in another case, regardless of his ethnicity or religion.

RE: “It’s one thing if only members of a persecuted minority get to comment on that minority; I understand that ancient prohibition. But when you have power– a lot, I say; or a ‘modicum of power’, as Foxman says — then you should be able to take some criticism.” ~ Weiss

SEE: ■ A Problem of Self Image (Mysh) from Richard Silverstein’s Tikun Olam site

An question on timing: If another Shipman said the same thing today, after so many others (some Jews among them) have said similar things, would he still be fired? (BIG-ZION might still try to get him fired, but would it work?) This is the acid-test-question. Is the conversation in America STILL only a Jewish-communal thang, or has the discussion become broader? Does the Iran fight with its over-the-top obvious BIG-ZION and Israel tie-in make it OK for non-Jews to enter this fray (the Shipman fray)? How about the Iran-fray? What impact has the Salaita-fray had on college administrators?

These tepid Zionist acknowledgements, wrapped in excuses for Israel’s crimes, remind me of the “States’ rights” cover story for slavery and racism, which is utterly demolished in this EXCELLENT article by Bob Cesca, with quotes from Ken Burns.

http://www.salon.com/2015/08/25/confederate_fantasies_the_donald_trump_surge_inside_the_dangerous_southern_mythology_creeping_into_the_gop_primary/

Shipman doesn’t wrap his comments in the required banality of tribal loyalty. There is NO reason a person would make excuses for overtly bigoted actions other than their being inwardly a bigot, however much they try to hide it and protest otherwise.