Whilst the State of Israel marks itself as the Jewish State, many Zionists and particularly liberal Zionists, often make a strong separation between Judaism and Zionism, noting that Zionism is essentially a secular ideology, and that its manifestation, Israel, is essentially a secular state. The separation between Judaism and Zionism is also common amongst anti-Zionists and amongst pro-Palestinian groups (including Jews and non-Jews) and the distinction serves to mark a critical separation between statehood and religion: that Zionism, as representing the idea of a Jewish “secular” state, manifested in the State of Israel, is not a religion, and that therefore opposition to Israel’s actions is not anti-Jewish, not anti-Semitic.

Mondoweiss recently published an interview with Zvia Thier, a former ‘liberal Zionist’, and she speaks very strongly about this separation.

But I am going to do something contentious. I am going to speak my mind about how this separation is artificial, clinical and untrue. I am going to make the point, that Zionism is a Jewish nationalism, and as such, a form of religion. Thus, making the point that Jewish Zionists are actually religious, even if they claim to be secular.

Now Tzvia Thier in the interview stresses the point that Judaism and Zionism are not one and the same, and that therefore anti-Zionism cannot be considered anti-Semitism. So far, so good. They are not one and the same – but they can still be very, very closely (if not inextricably) related. She makes the point, that there are ultra-religious Jews who are against Zionism. This is one that I have heard many times, mostly from pro-Palestinian activists – and I just don’t buy the heart of the argument, for the following reasons: There are religious Jews who believe that the ‘return’ to the ‘holy land’ of Zion must await the return of the Messiah. This idea has been generally accepted in Jewish culture for many centuries. But with the rise of Zionism, the nationalist vein of Judaism was lured to accommodate a man-made return. Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook (died 1982), the spiritual leader of the religious settlement movement, together with his father Avraham Isaac Kook (died 1935) were the founding fathers of the national-religious movement and advocated that man-made ‘return’ was not anathema to the arrival of the Messiah, but would rather hasten it.

Judaism is a religion which is not carved in stone. Jewish orthodoxy does not really use the bible as its daily guide, but rather the subsequent religious interpretations of it (which have historically taken form in the Talmud). Thus the stream of rabbinical interpretation of the scriptures is a central one in Judaism, and this means that it is open to discussion.

One can therefore say, that whilst Zionism and Judaism are not the same, they have married in no uncertain ways. Those ultra-Orthodox Jews who oppose Zionism, do this because of a rabbinical interpretation – which is more to do with timing than it is to do with morals. Were they to believe that the Messiah indeed had arrived this day, they would have no problem with enacting what they would perceive as a God-sanctioned ‘return’ and takeover of Eretz-Israel.

So I perceive that separation to be semantic. The non-Zionist religious movement does not essentially oppose Zionism morally; for them it’s a timing question.

Now to the ‘secular’ Zionists:

The belief in ‘return’ is more deeply rooted in ‘secular’ Zionism than one might think.

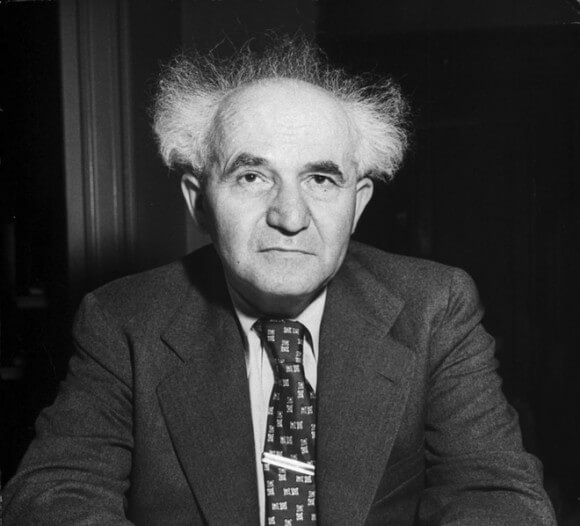

In 1936, there was a mass revolt of the indigenous Palestinian population, known as ‘The Great Arab Revolt’. The British government, which at that time controlled Palestine with its Mandate, sent a committee to hear out representatives of both sides and try to resolve the ‘Arab-Jewish conflict’. The chairman of the committee was Lord Peel and one of the witnesses to testify before the Peel Commission was the chairman of the Jewish Agency: David Ben-Gurion. Ben-Gurion spoke of the right of the Jews to the land of Israel. When he finished, Lord Peel turned to him and asked, “Mr. Ben-Gurion: Where were you born?” “In Plonsk, Poland,” he answered. Lord Peel continued, “If a man lives in a house for many years and suddenly, someone else appears and claims ownership of the house, international law dictates that the burden of proof rests upon the claimant, not the current occupant. Mr. Ben-Gurion: Do you have a deed or contract of sale that gives you the right to take the place of the native Arabs who have lived here for generations?” On the witness stand was a copy of the Bible, upon which the witnesses had sworn. Ben-Gurion suddenly picked up the Bible in his hand and declared, “This is our deed!”

With all its ostensibly ‘secular’ and ‘human’ wish to solve the ‘Jewish problem’, Zionism, despite a few aborted thoughts to colonize elsewhere, very quickly focused in on Palestine as its coveted target. It was ZION-ism after all, and the historical land where ancient Israelite and Jewish forefathers allegedly reigned and lived had been a strong element of longing in Jewish culture. But with Palestine, the claim to the land itself was to be more than incidental, for it was already inhabited. Such a ‘population replacement’ as the Zionists realized would have to take place to a considerable degree, could not be justified merely by claiming a wish to escape persecution, for the persecution of the indigenous population would counter the moral claim. Hence the accentuation of the ‘biblical’ and ‘Godly’ decree – even among secular Zionists, as the Ben-Gurion example shows.

The ‘return’ idea was a religious one, and it had to have its basis in the idea that the Jews are not merely people who share a faith, but also an ethnic heritage. One would essentially have to claim that they descended from the ancient Judeans. But such a claim is highly disputed scientifically, to put it mildly. Most Jews today are not even Semites (don’t originate from the Middle East), and the Zionists who colonized Palestine until 1948 were overwhelmingly European. As also Israeli researchers concede, there had not been a real exile in the time of the Romans (70 AD, when the Great Revolt of the Judeans was crushed). The Romans might have exiled some intelligentsia and leadership, but it was not their manner nor their interest to exile a proletariat which provided them with taxes and crops. In fact, as Ben-Gurion himself noted in a study he made in 1919 (together with Itzhak Ben-Zvi, future second President of Israel), the Palestinian proletariat seems likely to be descendants of the ancient Judeans themselves, who stayed and converted to other religions in the meantime.

So secular Zionists had to forge an unbreakable ideological nationalist tie with the land they coveted. Besides fostering the myths that they were coming to an ‘empty land’ (which would morally alleviate the notion of having to ethnically cleanse the indigenous population) and ‘making the desert bloom’ (which would serve the notion that they were actually helping the country and bringing progress – and never mind its people), the Zionists had to accentuate the religious myths concerning the relationship of the ‘nation’ with the ancient ‘forefathers’ and ‘Land of Israel’.

These are all myths, which, even if they were true, could not possibly qualify as any sort of ‘deed to the land’, just as Ben-Gurion’s bible-stunt with the Peel commission could not.

The inherently powerful aspect of religion is, that it transcends reason. And Zionism had to have this mystical aspect, rooted in Judaism itself, to persuade its constituency that this is a ‘special case’; to persuade that this is not just about religion, it is about survival as a nation.

Secular Zionists would often refer to Jewish persecution as an indication that such a nation does indeed exist. But persecution of a group of people who share religious beliefs does not necessarily prove they are a nation. If Sunni or Shia Muslims persecute each other, that doesn’t mean that there is a Shia nation and a Sunni nation. These are problems that need working out, for sure – but not necessarily through the establishment of a ‘nation state’ for that religion. Jewish persecution doesn’t mean Jews are a nation, only that others perceived them to be so.

So Zionism created the ‘Jewish State’. One could rightfully ask the simple question, how on earth could a state be ‘secular’ when by its very definition it is religious?

This is the trick. Zionism took the myth of the ‘Jewish nation’ from Jewish culture. It extrapolated the nationalist stream inherent in Judaism, and made it into an ostensibly ‘secular’ national movement. But this nationalist element depends upon the religious ‘counterpart’ to exist.

Thus I reach my conclusion, that Zionism is a kind of religion, masked as mere secular nationalism.

Correction: Originally this article did not recognize Rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook’s father, Avraham Isaac Kook.

I have some questions. If a government, Israel, is a religion, doesn’t it become a cult? If Zionism is a religion, funding Israel promotes a religion and doesn’t this violate the First Amendment?

In the religion of Judaism, just what was “Israel”? Was it a state or a state-of-mind? If it was a state, what were its boundaries? Was it three synagogues in Jerusalem, was it all the land extending to the Euphrates, did it include Paris, how about Madison, Wisconsin?

I believe in the theory of evolution. This was once science, but there’s more bang for the buck in religion. The theory of evolution is essential to my identity and faith. My ancestors came from Olduvai Gorge, and I have a right of return. I cite the fossil record. How much African property do I now own? How many Africans can I shoot to acquire this promised land?

I think that if if Zionism is a religion, that religion is a sort of “Golden Calf” religion — putting Israel as an idol, by Zionists, in place and “before” the God of the Jews.

But if, as this article seems to suggest, Zionism is a mere rabbinic interpretation of something, (of what, one wonders), so that he can say — and invites others to say — that Jewish belief, including belief by secular Jews, in the religious importance of Israel to Jews is a religious belief and not (merely) a political swangdangle, then we come down — as we always do anyway — to the question of power: Israel today belongs to Jewish Israelis not because they hold a particular religious belief (or even a particular nationalist political belief) but because they had the power to acquire it and the power to displace the Palestinians.

Now, as we also recall, Hitler had the power to displace the Jews (and many others) from his (also spreading outward) domain, and he did it with great vigor and, of course, with more killing, than the Zionists have used for their displacement of Palestinians. But it came down to power.

So, with power the essential element of the story, the question of religion does not arise, I should think.

And if Zionist Jews on American campuses want to say that anti-Zionism is antisemitism, or that anti-Zionism makes them fearful, I answer them thus: you may believe what you like and I and my anti-Zionist friends may believe what we like. These beliefs do not conflict, because they are held by different people. We do not care what you believe and do not seek to change your minds. (We may seek to change other minds however.) Go to your places of worship and do your thing. But we are Americans and have the freedom — until we lose it — to protest what we consider to be odious politics. and we intend to do so. And the Zionist practices (of making realities of the Zionist ideas) are political actions, not acts of religiousity.

And if anyone now-a-days seeks to resurrect a cannibalistic or human-sacrifice religion, however ancient, however sincerely held, they must expect that any attempt they make to put it into practice will be met with political or legal resistance. Just as Zionism-in-practice is met with political or legal resistance.

Thank you, Ofir! Finally some sense –so rare these days. The dogma (secular and allegedly anti-Zionist) holding the religion totally non-accountable for the nationalism has been rather heavy on everybody.

In fact, in addition to reading Zionism as a religion masked as nationalism, one could also take the whole as the natural trajectory of a strictly tribal religion, with (a) tribal god(s) opposing the Pantheon of the neighboring enemy tribes: given the peculiar character of this world view, it would naturally evolve into racial nationalism in the century of mainly German-inspired romantic nationalisms.

Thanks for the informative, thought-provoking essay, Jonathan. It’s a good reminder of the complexity of these matters. Defining “religion” is, of course, famously problematic. Many definitions include some element of the supernatural, but not all. The sociologist Emile Durkheim used various language in various definitions of religion, but the one I most recall (and find most apt in this context) was something to the effect of “a people worshiping itself.” That doesn’t need to include a supernatural element (though it may).

It’s a commonplace observation that people in Europe gradually lost faith in the supernatural element: the elites in the 18th and 19th century, with the masses following at various points in the 20th. They responded to the loss in various ways. One scholar of religion (William Parsons) suggests that the academic study of religion is itself a form of “mourning religion.”

It is likewise a commonplace observation that for many Jews, the Holocaust marked the death of God (announced long before by Nietzsche), and that for many of them Israel became His replacement.

The practical implications of this, if any, I leave to others to say. It seems to me that most of us here would agree that–while it may complicate matters, while it may explain part of what makes a solution so difficult, and while it may be an additional motivation for compassion and understanding for everyone involved–it does not obviate the needs and rights of Palestinians.

In 1948, when Truman was handed a statement from his staff which said that the U.S. government recognized and endorsed the creation of “the Jewish State.” He crossed out the words “Jewish State” and wrote, “State of Israel.” Only then did he sign his name.

Atzmon’s view in his book devoted to Jewish identity politics, the Wandering Who?, points to much in accord with Jonathan Ofir’s view here.