-1-

Today the shepherds wanted to set out at dawn. In summer, here on the outskirts of Jericho, by 9 or 9:30 in the morning it’s already over 38 degrees (100 Fahrenheit)—too hot even for goats. So we leave Jerusalem at first light, and by 6:30 we find Mhammad deep in the desert, close to the fenced-off date-palm grove of the settler Omer, who calls all the shots. Mhammad greets us happily; he’s in a good mood; so far things are quiet. “Soldiers? Have you seen any soldiers?” he asks. “Not yet,” we say.

The goats are busy with their lean pickings. Dried-out thorns, a shred of corrugated cardboard, a few leaves—all this constitutes breakfast in the summer. They stand on their hind legs, stretching hopefully toward the higher branches of the tamarisks. It will be months before the rains come and something edible and green re-appears. Among the goats there is one ancient, supremely dignified buck with a long white-brown beard. Mhammad says he’s their leader and commander, mudir. Who would doubt it? The mudir moves slowly, regally, as befits the owner of this patch of creamy rock and sand.

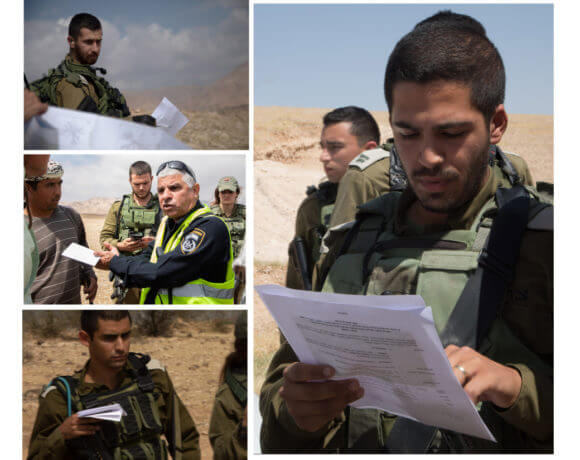

After an hour, a little longer, the soldiers arrive, as they always do. I recognize the officer; he’s not a bad man. But he’s carrying the cursed piece of paper declaring this area a Closed Military Zone, with a map attached. According to the map, the shepherds have to stay clear of a huge stretch of land that reaches up to their houses, some three or four kilometers away. Meanwhile, Mhammad and his friend have made a fire and boiled tea, and they’re sitting in what, with a little imaginative effort, might be called “shade,” under the branches of a spindly shrub. They’re eating breakfast: fresh pita dipped in olive oil. They pay almost no attention to the soldiers who have come to disturb this feast. We photograph the illegal order and the map and we tell the soldiers to go away; the shepherds will have to move on. The officer clambers back into his jeep. It’s hot, he’s performed the daily ritual, now he waits on the hill to be sure the order is obeyed.

These shepherds can’t be rushed, and we are certainly not going to urge them forward, or backward, toward home. Why should they hurry? It’s their land. Omer is a cruel intruder. The soldiers are soldiers. Time flows in desert rhythms. Mhammad carries no watch, and occasionally, rarely, he asks us to tell him the time. I think he lives mostly in the slow and beautiful flow of goat time: when the goats have eaten enough, they begin to saunter, or sand-swim, home. They don’t have to be told. From time to time Mhammad gently calls them to order: “Pzhee (high pitch, almost a whistle); khakhakhakha (deep in the throat); cluck-cluck-clack-cluck (flapping the tongue).” It’s a language I’d love to learn. Sometimes he throws a pebble at a sheep or goat who has strayed from the path. By now the soldiers are gone and the sun is high.

“I’ve tired you out today,” he says to us, apologetic, concerned for our well-being; we deny it. I offer him really cold water, and he takes it, a long good gulp, standing on a rock near his tethered donkey. I feel like a lean dry thorn myself, with the incontrovertible happiness of being a thorn.

-2-

Khan al-Ahmar, we fear, is about to be demolished. The government has announced it, and the Supreme Court, to its eternal shame, has approved it. Since the early 50’s, the Jahalin Bedouin have been living here, after the army chased them off their lands near Tel Arad in the Negev. They’re deeply rooted now in the brown-red hills on both sides of the big road leading from Jerusalem eastward, downhill, to Jericho. That redness (limestone tinged with iron oxide) gives the site its name, the “Red Caravanserai”. Caravans once, not so long ago, would spend the night here on their way to the spice lands in the south. The Good Samaritan of the parable is said to have passed nearby; just down the road there are the remains of a Byzantine monastery that marked the site. On a day like today, rife with wickedness, it’s good to remember that Samaritan who did the right, the only human, thing.

We see the Bedouin tents of Khan al-Ahmar each time we drive from Jerusalem to Jericho and each time we return to Jerusalem from the Jordan Valley. But in the last decades, the settler-suburbs of Maaleh Adumim and Kfar Adumim have spread over the high ridges nearby. These people—or at least some of them, let’s not generalize — don’t want to see an Arab face. It spoils the view. So on the one hand, settlers have been driving the government’s campaign to expel the Jahalin. A ruthless racism rules this policy. On the other hand, there are weighty geopolitical considerations. Khan al-Ahmar is the portal, both tangible and symbolic, to area E1, the vast swathe of land east of Jerusalem that Israel wants to annex, thereby cutting the West Bank in two. If the army expels the 172 souls of Khan al-Ahmar, the other 1200 or 1300 Jahalin Bedouins who live close by will be easy prey.

Even if the school were not there, we would be facing a war crime; it has no other name. But the school magnifies the crime many times over. Today is the first time I’ve visited it. It’s an eco-friendly school, lovingly made from mud or clay and old tires. On the outside walls there are paintings of the Dome of the Rock and, surprise, a white sailboat floating down the non-existent or invisible rivers of Jerusalem to some place, we must assume, of freedom—some place the bulldozers are barred from entering. An inscription in Arabic says: “We will remain here as long as the za’atar and the olives remain.” At the entrance there is a sign declaring this school to be under the supervision of the Palestinian Ministry of Education. This is the Jahalin’s first-ever school. The courtyard is swept clean. Activists from the Combatants for Peace and other organizations are milling around; they have come to protest the crime-to-be. So there are speeches and embraces and kisses and many smiles, along with that unrelenting ache.

Police and soldiers were here several times this week, probably to prepare the ground for the demolitions. They’re a lot like the heartless thieves in the parable. The government has announced that it will resettle the Jahalin in Abu Dis, next to the municipal dump that is now a high hill known simply as “Jabel,” The Hill. No one can live on or near the Jabel. The stench is overpowering, and disease rampant. To dump these human beings on the dump is one of those acts that tell all.

But for me, there is something more. To tear down a school is possibly worse even than breaking a home into pieces and burying the pieces in the sand. How many homes have we rebuilt after the army took them down? We’re almost used to it. But a school? Where children first learn to read, where they dream their dreams and play in the courtyard and sing the multiplication table and recite the poetry of the desert and say their prayers? I’m a teacher. I have spent most of my life in classrooms, teaching this and that, languages, thoughts, memories, poems. The mud-and-tires school of Khan al-Ahmar is like any of the others, only more so, like the university I have loved, like the school in Iowa where I learned to read and first fell in love—an almost holy place. It’s not a word I use.

This post first appeared posted by Margaret Olin’ on her site, “Touching Photographs, Thinking with and about Photographs.” Its title there was “June 22, 2018 Al-Auja, Khan al-Ahmar – text by David Shulman.” The text is copyright Shulman. It and the photographs by Shulman, Olin, and Amir Bitan are republished here by permission. The photos appear in full dimension in that version.

Incidentally, this story appeared today in the New York Times, so people can read about in the NYT’s he-said-she-said style:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/24/world/middleeast/israel-bedouins-demolition.html

Now, however, the brakes may be off. With the Trump administration providing diplomatic cover, right-wing ministers in Israel pressing to exploit that while it lasts and international support for the Palestinians focused for the moment on Gaza, a new ruling by a settler-majority panel of Israel’s Supreme Court appears to have freed the government to proceed with the removal of entire Bedouin communities on the West Bank. Advocates of the Bedouins say this would be a war crime: the forced transfer of a population under the protection of the military occupation.

And some pushback –

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/ex-jewish-agency-chief-condemns-planned-demolition-of-bedouin-village-1.6173863

The former Jewish Agency chief and Israel’s ex-ambassador to the U.S., Sallai Meridor, published an open letter condemning petitions to the High Court by his settlement in support of the demolition of the Bedouin village of Khan al-Ahmar in the West Bank.

Stories like this sink quickly to the bottom in the sea of NYT, Guardian etc. propaganda. We live in an era where, for many, words matter more than actions and media cues determine which people are worthy of “solidarity”.

Israel can slaughter unarmed civilians with near-impunity and the US and its allies can bomb and drone to death people in Muslim nations but the so-called SJWs, who are supposedly against racism and bigotry of all varieties, stay silent. They react like automatons to media optics showing crying or mutilated children on the US/Mexico border and in Syria, they get outraged over real or imagined offensive language, but the situation in Palestine or Yemen barely elicits a response. Trump’s travel ban is, rightly, opposed but his continued bombing of Muslim countries and unconditional support for Israel barely elicits a reaction.

Maybe if they read more articles like this one, depicting Palestinians as human beings suffering under a cruel occupation, those ostensibly standing for social justice would take note. Considering how they let the media and corporate Democrats lead them, and their general narcissistic attitude and inability to make connections between domestic and foreign policy and between the Trump regime and those of his predecessors, I am not hopeful.