Last fall, Nas Daily held a talk at McGill, hosted by the McGill Arab Student Network. But many weren’t feeling the vibe.

The event page on Facebook quickly drew controversy as Palestinian students from various Canadian campuses descended into a protracted and far-reaching back and forth with event organizers in the comments section and in subsequent posts.

Commenters highlighted Nas’s role in whitewashing Israel’s crimes against the Palestinians, with one commenter, Yasmine Mosimann, putting it succinctly: “It is not his ‘background’ that I and any other mildly informed person object to. It is him telling Palestinians to ‘move on’ from colonization, theft, ethnic cleansing, and mass murder; things that are not in the past, but are realities for those under blockade and occupation as well as in refugee camps. Inviting a person who makes videos about over 70 Gazans being shot down by saying ‘both sides are to blame’ does not get to be protected under the guise of being apolitical.”

For a Palestinian social-media celebrity who enjoys exposure to 10 million followers yet presents a dangerously narrow view of the conflict that minimizes Israel’s responsibility, it was also little to no surprise that Palestinian human-rights clubs at McGill and Concordia scrambled to release statements of condemnation.

As the arguments on Facebook continued well into the week, the page administrators deleted comments and ignored pleas to cancel the event.

In the end, the event was held to a packed audience.

This episode was emblematic of the growing trend in the Canadian-Arab community to engage in cultural and professional event programming to the exclusion of politics and political education—to the extent that’s possible.

Just as Nas tries to avoid the unavoidable by turning a deeply unequal political relationship between Israel and the Palestinians into a cultural misunderstanding between Jews and Arabs, the Arab associations emerging across the Canadian neoliberal landscape find themselves in the awkward position of having to make being resolutely non-political a point of pride, a practice that includes avoiding those engaged in progressive political organizing out of fear of the shame that inevitably follows such interactions.

Consequently, in the Palestinian context, we are witnessing an attempt to redefine our identity. We’re seeing a shift from an identity based on our collective project of political emancipation and resistance that began with the pre-1948 revolt against the British Mandate and developed throughout the Palestinian revolution post-1948 Nakba, to an identity that sees our national symbols like the kuffiyeh or the olive tree denuded of their historical and political meaning. We are left with a culture that is being depoliticized and being ‘made safe’ for our elites’ integration into Canada’s ruling classes at an alarming rate, while exploitation and oppression suffered by the majority among us only deepen.

An online search of Arab-community events turns up an endless array of galas, seasonal mixers, networking events, professional-development conferences, more networking events, youth connects and entrepreneurial- and personal-branding workshops. Did I mention networking events? The worst part is that these copycat events are not even hosted by a single organization, but by numerous competing Arab associations and Arab ‘professional associations.’ And when they do host a ‘political’ event, it involves having Arab youth meet representatives from each of the three major Canadian political parties, as if presented with career options or consumer goods rather than opportunities for meaningful political engagement. Yes, this includes the Conservative Party that promotes—and enacts when elected—an atrocious anti-Arab, pro-Israel policy.

Similarly, on university campuses there have been several attempts in recent years, both successful and unsuccessful, to form Palestinian student associations that prioritize narrow identity-related concerns and entertainment through food and dance over direct political engagement and education. In one such case, a Palestinian student association replaced a Students Against Israeli Apartheid chapter and initially kept overtly political events at arm’s length in its programming.

This was simply not the case a decade ago. Arab students displayed an acute awareness about the role of American and Israeli foreign policy in shaping their lives. They prided themselves with an understanding that injustice in the Middle East is tied to injustice everywhere. Subsequently, Arab students had a sense—held by an internationalist framework—of the need to organize against injustice and to build solidarity links between struggles against injustice.

To be clear, we know that cultural expression is an imperative in the struggle to defend ourselves against attempts to wipe us from the historical record. But, during my time as a student at York University and student activist in the anti-war movement, Palestinian identity was defined by cultural symbols tightly interwoven with a progressive political framework focused on building solidarity with others in the struggle against war, occupation, colonialism and imperialism, and with the championing of a better world for all.

The same cannot be said for the experience and worldview of many Palestinian students today.

This phenomenon is by no means limited to the Arab community; it corresponds to the integration of the professional middle and upper classes of immigrant communities into the ruling liberal elite (small l).

While Canadian multiculturalism has largely succeeded in securing diverse representation by integrating a narrow layer of the ruling political and economic classes in immigrant communities to act as power brokers, inequality within these communities, and within Canadian society more generally, has continued to grow. And as inequality grows, the interests of these elites grow further and further apart from the interests of the average members of these communities. The result is that there is now a more pronounced convergence between the interests of elites in immigrant communities and the interests of those in the more traditional Canadian ruling classes, and a more pronounced divergence of these interests with the interests of the majority of people in their own communities. In other words, the elites in immigrant communities now have more in common with the rest of the Canadian ruling classes than they do with the majority of people in their own communities.

Omar Alghabra, a well-known Arab politician, for example, has more in common with the diminishing segment of upwardly-mobile middle class and wealthier Canadians in the Greater Toronto Area than he does with poor and working-class Arabs in the same area. And it doesn’t matter whether he began from humble origins; the point is that now that his interests are aligned with the political elite in the Liberal Party, he can no longer afford to stand up for those in his community who are struggling to make ends meet. That’s why our community elite will refuse to support causes or policies that may pose threats to their own interests or those of their friends and colleagues, whether that be supporting the unionization of workers that they employ, or by supporting Palestinian human rights.

This turn in Canadian-Arab and Palestinian communities represents the ascension of depoliticized cultural expression to fit the needs of our community elites, rather than the universal realities of oppression and material deprivation that inform the lives of poor, working and oppressed people around the world.

The withdrawal of many Palestinians in Canada from political activism and human-rights work, and the retreat into narrow cultural expression, will inevitably have the effect of weakening the bonds of solidarity that have proven crucial to rendering the oppression of Palestinians as increasingly visible to mainstream audiences. If our community elites succeed in peddling representation and entrepreneurship as realistic substitutes for political organizing, it risks hitting the solidarity movement’s greatest strength—its existence as a forum where Palestinians and non-Palestinians work together towards a struggle fundamental to our common liberation.

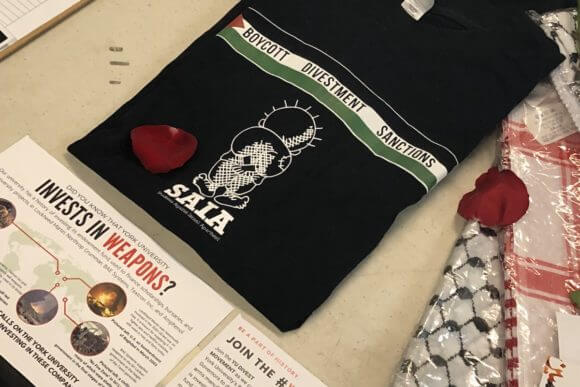

It is in this context that Nas Daily was invited to speak by the McGill Arab Student Network. But it is also in this context that resistance to this shift has arisen in the form of new actors like the Association of Progressive Palestinian Canadians (APPC) and the social-media controversy that erupted in the wake of Nas’s event. Make no mistake, the recent endorsement of BDS by the Canadian Federation of Students, a motion brought forward and had its groundwork laid by Palestinian organizers, is an indication that the politics of solidarity remain a force to be reckoned with inside our community.

But only an in-depth examination of the needs of the poor and working families of our community—here and in Palestine—can reveal how the politics of solidarity can secure Palestinian culture and keep it positioned squarely within the framework of a Free Palestine and a better for world for all.

always telling Palestinian arabs what they “must” do. the intolerance of the left wing so-called progressives on full display. not much different with jews except the proportion of Palestinian dissent is smaller as social/legal repercussions are more severe. that is gradually changing right along with PWs dream of a great divide among American jews and zionism.

According to the bio Hammam Farah is Palestinian. I have to conclude that DaBakr prefers essays that advocate surrender by natives to white racist Euro colonial-settler invader-genocidaires.