BLACK POWER AND PALESTINE

Transnational Countries of Color

by Michael Fischbach

278 pp. Stanford University Press $25.95

Michael Fischbach’s Black Power and Palestine is the best book yet written on the contemporary history of Afro-Palestinian solidarity. The book is invaluable as a scholarly record of Black efforts to organize with and in support of Palestinian liberation, but also as a political argument about the centrality of Palestinian solidarity work to building internationalist, anti-imperialist solidarity in our time. Indeed Fischbach demonstrates that, since the Vietnam War, Palestinian freedom struggle has been the most important gateway into radicalism for several generations of African-Americans.

Transnational Countries of Color” by Michael R. Fischbach, Stanford University Press, November 2018.

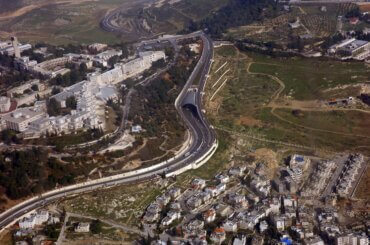

Stokely Carmichael coined the term “Black Power” in 1966 while appealing to members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to march militantly in Mississippi. Yet Fischbach makes the term elastic, encompassing Black efforts before and after that moment to theorize and practice a politics of self-determination in support of Palestinian national liberation struggle. Thus his study moves from 1959—the year Martin Luther King, Jr. visited the West Bank and East Jerusalem to assess the plight of Palestinians there—to 2015, when activists Kristian Davis Bailey and Khury Petersen-Smith gathered more than 1,000 signatures to a “Black for Palestine” solidarity statement.

Fischbach’s durable thesis is that African-American radicals have generally perceived Palestine as a “country of color” ruled by the same white, western imperial interests that have subordinated Africans, Asians and other “Third World” subalterns. This was the argument that made both the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (or SNCC) and the Black Panther Party turn hard for support of Palestinians, especially after the so-called 1967 “Six-Day War” which made explicit for many Israel’s imperial role in the Middle East. The “country of color” argument was also the source of Black radicalism’s assertion that African-Americans were an oppressed national minority, as internally colonized in Oakland as were Palestinians under settler-colonial Occupation in Ramallah.

Fischbach carefully demonstrates how this most radical of positions in the 1960s became the key pole of attraction and repulsion for Black Americans—and Jews—seeking to stake out their own positions on Zionism, Jewish statehood, Palestinian liberation, and Black freedom struggle. His nuanced treatment of Martin Luther King in the book is exemplary of this. King’s 1959 visit to the West Bank included an unscheduled meeting with Vicken Kalbian, a physician whose family was forced to flee Palestine in 1948. King learned from Kalbian for the first time about the Nakba. After returning to the U.S., King was invited several times by officials of the Israeli state to visit Israel, but never acted on the invitations. In 1967, the Six-Day War and the militant responses of SNCC and the Black Panther Party forced King to walk what Fischbach calls a “tight rope.” Before the war, King had planned to lead a peace delegation to Israel. Now he cancelled, in part, Fischbach speculates, because of his publically outspoken criticism of the U.S. war against Vietnam. Yet to appease Israel supporters, King lent his name to a New York Times paid advertisement purchased by supporters of Israel, and a short time later, spoke of Israel’s “right to exist as a state in security” (85). Fischbach makes clear that King was both hypersensitive to Jewish pressure and profoundly challenged by Palestinian oppression.

Two other spellbinding figures in the book are Bayard Rustin and Andrew Young, symbolic bookends of Black political polarization around Palestine. Rustin, a pacifist, openly gay lieutenant of King, and one of the organizers of the March on Washington, moved increasingly to the right after 1963. Alarmed by the rise of the PLO in Palestine, and seeking to pressure the Gerald Ford Administration to ramp up support for Israel, Rustin formed the group BASIC (Black Americans to Support Israel Committee). Rustin convinced dozens of Black American notables—among them novelist Ralph Ellison, former Congress of Racial Equality leader James Farmer, musician Lionel Hampton, Civil rights legend Rosa Parks, baseball star Henry Aaron, musician Count Basie, and others, to sign a “Statement of Principles” in the November 23, 1975 edition of the New York Times. The statement affirmed U.S. support for Israel.

Also a signatory to BASIC was Andrew Young, another former King lieutenant, and by 1975 a member of Congress. In 1977, Young was appointed U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations by President Jimmy Carter. In 1979, Young resigned his position after meeting with Zehdi Labib Terzi, the PLO’s U.N. observer. The meeting broke with an official U.S. state position not to meet directly with the PLO. Novelist and activist James Baldwin, himself a stalwart defender of Palestinian human rights, defended Young and excoriated Carter in “An Open Letter to the Born Again,” accusing Carter and the U.S. of support for Israel as a means to consolidate Western imperialism and Christian Zionism in the Middle East. Baldwin’s own support for Palestinians had been nurtured by SNCC and the Black Panther Party.

Fischbach misses one major opportunity in the book, namely to narrate in depth the intertwining of African-American support for the end of South African apartheid and Palestinian liberation. Mainstream Black support for the Boycott, Divestment Sanctions movement against South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s was a major progenitor of Black support for the Palestinian BDS campaign launched in 2004 by Palestinian civil society and directly inspired by the South African example. Since 2004, Black support for BDS—from singer/songwriter Chuck D. of Public Enemy, to South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu—is the most compelling and enduring legacy of the Black Power narrative Fischbach otherwise expertly describes.

Fischbach’s book is an essential text for our times. The conjoined support for Palestinian human rights and BDS by Somali congresswoman Ilhan Omar and Palestinian congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, his book helps us understand, is no historical accident. Nor is Donald Trump’s racist and racialized use of Israeli Zionism to attack them. This dialectic of resistance is embedded in the deep muck of American imperialism, Christian Zionism, and Israeli setter-colonialism. That it will not stay not buried is a hopeful legacy Fischbach’s book can help a new generation of activists build upon.