Last Friday night, I settled into my seat in a movie theater in the far Northwest reaches of Washington, DC, preparing for my first solo cinematic experience. I was at the opening night of the 24th annual Arabian Sights film festival, where famed Palestinian director Elia Suleiman’s latest film It Must Be Heaven was headlining. Truthfully, there is no better film to watch alone; Suleiman’s absurdist, highly symbolic style lends itself well to both silent, internal reflection and uproarious laughter, which enveloped the theater throughout the film and made me feel like I was watching it with several hundred of my closest friends. It Must Be Heaven embodies the seeking energy that its title suggests. Suleiman and the viewer are not quite in paradise, as the small but frequent indignities pile up behind Suleiman on his travels throughout the film, but peaceful olive groves and the simple satisfaction of a glass of wine and a cigarette show that he is not in hell, either.

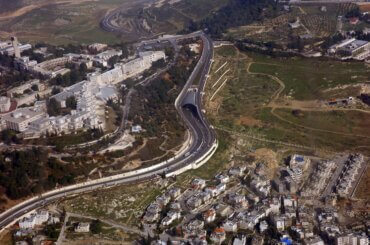

The film follows Suleiman from Palestine to France to the United States and back again, with the classic dark comedy that characterizes much of Palestinian film in general and Suleiman’s work in particular. He temporarily abandons his home in search of something that remains unnamed but may well be an escape from the daily reminders of trauma that haunt his life in Palestine, from passing Israeli soldiers with a blindfolded Ahed Tamimi-lookalike in their backseat on the highway to police officers who steal a pair of binoculars only to keep watch on Palestinian civilians from just a few meters away. A deep mistrust of and irreverence toward those in uniform underpins the narrative, and with good reason. Suleiman’s satire of French police officers circling each other on segways and New York cops dodging mommy fitness classes as they chase a Palestinian solidarity activist (aptly dressed in angel wings for Halloween) through Central Park are among the most brilliantly funny and incisive moments in the story.

It Must Be Heaven is, unquestionably, a love letter to Palestine. The narrative opens and closes in Suleiman’s native Nazareth, the Israeli occupation and accompanying resistance hanging just out of sight in every scene of daily life in the city. But as hilariously as Suleiman critiques Americans, the French, and the Israeli soldiers occupying his homeland, he doesn’t shy away from turning his sharp eye inwards as well.

The opening scene in the Paris chapter of the narrative, in which Suleiman sits at a sidewalk café transfixed by the short skirts and haughty pouts of the parisiennes passing by, reads at first as a sexist misfire that seems like an uncharacteristically lazy choice to introduce Suleiman’s misadventures in the French capital. Closer examination of this and other scenes, however, such as one in which two comically hypermasculine brothers chastise a Nazareth bar owner for serving their sister chicken in white wine sauce while simultaneously downing glasses of Johnnie Walker Black Label, reveals subtle jabs at the elements of Palestinian culture that Suleiman himself wishes to critique. In this context, the café scene in Paris transforms from a misogynist series of tightly shot frames of women’s bodies into a self-reflective critique of the lionization of Western culture and European beauty standards. The average viewer would be forgiven for missing such a nuance, but the chuckles from the crowd at Suleiman’s wide-eyed wonder over Parisian legs evidently indicated that they were in on the joke.

Much of the film leverages black humor, and a number of vignettes elicited knowing laughter from the audience with whom I watched it, who had possibly experienced their share of similar farces and indignities. Among the most obvious socio-political commentary are the scenes that show Suleiman shopping a film in Paris and New York, where a French studio exec rejects the story because it isn’t “Palestinian enough,” and an ill-fated attempt by Gael Garcia Bernal (as himself) to get Suleiman noticed by an American producer falls flat. Bernal sings the praises of Suleiman’s latest, a comedy about peace in the Middle East: “That’s funny already,” the platinum blonde-haired producer quips before sweeping out of the building with Bernal, leaving Suleiman blinking in their wake and perhaps wondering along with the viewer what mix of comedy and tragedy it takes to get a Palestinian film produced abroad.

No matter where he goes, it seems, Suleiman faces either tokenization or dismissal. His reactions in the face of such absurdity are the saving grace that prevent viewers from descending into depression or resignation as a result of such ignorance; the raised eyebrows and quizzical look in his eye indicate skepticism but not surprise at the lukewarm responses to Palestinian stories that refuse to conform to Western narratives consisting exclusively of tragedy and suffering.

Indeed, the remarkably similar restrictions and ignorance Suleiman encounters both in Palestine and abroad take on a ridiculous, comedic sheen counterweighted by the seriousness of the central question he asks again and again: will there be Palestine?

A grizzled tarot reader in New York City supplies the answer, telling a doubtful Suleiman that Palestine will have its independence, but not in either of their lifetimes. This sentiment is echoed by perhaps the most abstract scenes in the film, which see Suleiman drive to the outskirts of Nazareth to a nearly-deserted olive grove under the bright sun. In the first scene, he watches a woman in a veil and the traditional Palestinian thobe make a never-ending trek back and forth across a line of olive trees, setting down a large metal water container at one end of the row only to spin around and backtrack to do the same with an identical water pot. Suleiman follows her back and forth from the other side of the trees, peering through the branches to observe her.

The camera cuts away before we ever find out how the scene ends, but Suleiman revisits the olive grove upon returning to Palestine. He watches the woman carry the same water containers back and forth, only they are empty now, and then she suddenly kneels, pulls off her veil, and shakes her hair out over her shoulders. Rather than continue her infinite trajectory between the two containers, she hoists one over her head and the other onto her hip, striding off into the sunset. Whether the woman personifies an allegory for shaking off tradition is up to the viewer, but the point is clear if slightly heavy-handed: forward movement is unstoppable.

In what would have been an obvious choice for the ending scene of the film but instead merely precedes it, the organizer of a panel of Palestinian cultural figures buys Suleiman glass after glass of arak at a neon-lit New York dive bar after the event. An Arabic speaker of unknown nationality, he informs Suleiman that Palestinians are strange because while everyone else drinks to forget, they are the only people who drink to remember. Suleiman cocks an eyebrow and lights a cigarette in response. The moment calls up all the previous scenes in which Suleiman imbibes; he is constantly accompanied by a glass of red wine or arak whether on his patio in Nazareth or on an airplane over the Atlantic. What appears on the surface to be a mere bon vivant habit takes on a much deeper, more melancholy cast in an instant: what is it exactly that Suleiman is trying to remember?

It Must Be Heaven exists in the space between memories of the past and visions for the future, encompassing both but committing fully to neither. Rather, it is a collection of stories that define the inner and outer worlds of Palestinians within the occupied territories and the diaspora. These sketches are quintessentially Palestinian in their specifics and yet seek to answer universal interrogations about what life is like when humans seek home, belonging, and normalcy outside of the soil on which they were born.

The Arabian Sights film festival is running until October 27th in Washington, DC. Learn more about the films and buy tickets here.