In my re-reading, and teaching, of Ghassan Kanafani’s literary works, I came across one of the first short stories I encountered as a teenager. I was about 14 or 15 years old at the time and there was something adventurous and dangerous about reading Kanfani’s banned books. Perhaps for this reason I would read these inspirational short stories and novels late into the evening.

The writer was martyr who wrote about other martyrs, and I was a young reader surrounded by stories of real martyrs, relatives and otherwise. One of the first stories I read (and I must admit that I never thought they were fiction at the time) was “The Land of Sad Oranges.” Later, it became my choice when I was asked to teach an introductory course on literature in Gaza. I wanted to teach it from the emotional perspective of that teenager — albeit with the consciousness of an adult activist. Tough task, I must admit! But here is what I did with my students after reading the story for the umpteenth time. Every single time, the aesthetic shock leaves me speechless, I must say.

The Nakba from a Child’s Perspective

Neither on a first reading, nor on a second can the reader comprehend the social, historical, and political complexities confronting the Palestinian family in Kanafani’s short story. That is, such complexities in their turn affect—and are the effect of— the story’s setting, space, time, characters and their roles. It is a story, or rather a journey, that takes consciousness as its ultimate goal.

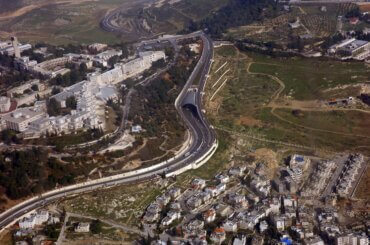

We are led, from the very beginning, to Acre; a journey that does not seem to be tragic. The narrator, whose narration is addressed to somebody we do not know, seems to be remembering what he could not understand as a child. He says: “you and I and the others of our age were too young to understand what the story meant from beginning to end…” Thus, the short journey from Jaffa to Acre does not seem to be tragic for him. However, the tragedy becomes clearer when the family is forced to move from Acre to Lebanon. It is significant that the narrator defines the ‘Other’ as Jews attacking Acre, i.e. the reason behind the displacement of the Palestinians is the attacks of the “Jews.” At the time, they were not Israelis yet.

Moving from one place to another is paralleled with a shift in narration. In this way the child’s narration reflects the movement towards consciousness. And the relationship between orange trees and the Palestinian family, as a representative of all other Palestinian families, becomes an intimate one. The first time orange trees are mentioned is when the family heads towards Ras Naqurs: “The groves of orange tree followed each other in succession along the side of the road.”

It becomes clear, then, why oranges move with the Palestinians wherever they go, why women weep when they buy oranges, and why the father “bursts into tears like a despairing child” when he gazes at the orange fruit. The tragedy becomes clearer when the family leaves the land of oranges; the child/narrator himself starts weeping. It is not, then, a normal land, but rather a symbol for all that the Palestinians leave behind. This is an intimate relationship between (wo)man and her/his land/oranges. That is to say, s/he is the land:

And all the orange trees which your father had abandoned to the Jews shone in his eyes, all the well-tended orange tree which he had bought one by one were printed on his face and reflected in the tears which he could not control in front of the officer at the police post.

If the Palestinian is separated from their land, s/he is lost; their separation is tragic.

Of course, the outcome of such a tragedy is that the child narrator understands that he has become a refugee; one of many who are confronted with the dilemma of finding a shelter and food. Political problems lead to socio-economic repercussions. The child’s consciousness gets transformed and his awareness of different ways of exploitation—be it political, or economic—widens. He even questions his individual responsibility as a child: “Pain has begun to undermine the child’s simple mind”.

The Palestinian Aftermath

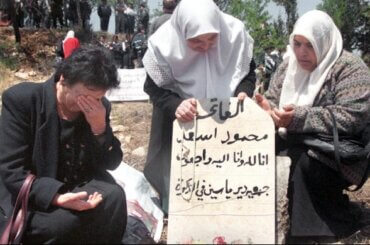

The social problems Palestinians suffered from after leaving their land, have added new dimensions to their tragedy. Even the very concept of family, as we know it, was altered after 1948. Of course, the family as a social network based on socio-economic relations, is also related to some other elements. When those elements are left behind, the family itself becomes questionable. Within this context, one can understand why the narrator says: “the happy, united family we left behind, with the land, the house, and the martyrs killed defending them.” It is significant that the narrator synthesizes all these concepts together. We are, therefore, led to make this synthesis: the homeland, the land, the happy family, the house, the orange trees, and the martyrs are all the same.

What do my students think about the story, 30 or 40 years since I first read it? One amazing reaction came from a student who read it to her grandmother who herself was born in Jaffa, the land of sad oranges. The grandmother cried bitterly, I was told. Another group of students thought it was necessary to keep reminding themselves of the Nakba by teaching similar stories. But the question that was raised by most of them was about the solution to the narrator’s dilemma, and how to make the orange trees happy again? Would the establishment of an independent Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza mean anything to the Nakba generation who lost so much?

Is this book available in English? Cannot seem to find it anywhere.

Thank you so very much for sharing this hauntingly powerful story and your impressions with us, Professor Eid. Your students are obviously enriched by your scholarship and so am I. The histories of the Palestinians will never be erased nor forgotten.

SO moving….