There are pains that never heal, and there are institutions that are designed to dehumanize others. The institutions of a colonizing power are designed to not only steal land but they are also intended to inflict pain on the hearts of its indigenous people. Since 1948, an ongoing genocide, affecting the freedom and sovereignty of the Palestinians over their bodies and movement has resulted in their slow death, both mentally and physically. Even though many Palestinians have acquired new citizenship from developed nations all over the world, which allows them to move freely, they are not be able to re-enter Palestine and visit their loved ones in Gaza, with a high probability that they will be abused by border officers if they do attempt to enter. In this way, the flesh has become an identifier of the Palestinians of Gaza. As Weheliye says “hieroglyphics of the flesh… remain a potent potential that lingers affixed to the racialized body as not-quite-human”. [1] We have been dehumanized. I was dehumanized. I am being animalized by a colonial settler state named Israel.

On the morning of the 3rd of December 2019, I woke up tired after a long night of travel from Sweden to Beirut to see several missed calls. I opened my social media to see who was calling me with such persistence. I was horrified to see posts mourning my father on the social media pages of my friends and relatives. The shock of losing a father without seeing him for twelve years is not only painful, it feels like I too have succumbed to my own death. It is as if someone is butchering my heart in front of my eyes, while I am silently swimming in tears and anguished cries.

Since I left Gaza in 2007, Israel has denied my entry back into Gaza and has revoked my registry for no obvious reason, other than my being from Gaza. My father died with sorrow and pain because of the actions of Israel and I myself will live with sorrow and pain, forever remembering how the settler colonial Israel inflicted this pain on myself, my father and my people by building virtual and physical walls between loved ones. This has been a destructive and torturous policy of Israel for many years.

In Beirut I was just five hours by road to Gaza (if there was no colonial Israel), and just a 40-minute flight to the Gaza airport (which Israel completely destroyed in 2001), and a nine-hour journey to Gaza via Cairo through the Sinai desert by road, which now takes approximately 48 hours even though it is less than 500 km. The psychological torment that I went through after learning of my father’s death, as I calculated possible routes home to see my family while realizing the heartbreaking impediments to my return was enormous. In that moment and in all moments when I think about going home, my vulnerability can be best described as the animalization of my being due to borders and my role as a border transgressor in the eyes of both the Egyptians and Israelis. As Agamben [2] and Mbembe argue, contemporary border politics exposes the border transgressors to death rather than directly using its power to kill. [3]

The day I left Gaza, my father was the last person I saw. I left my home around five in the morning, the same time that he passed away, many years later. The morning I left, I was at the mosque for early prayers. I went to say goodbye to my father. With a farewell shake of hands and kisses on cheeks, I heard the crying rattles in his throat and saw his tears. His last words were ‘Make me proud as always’. I said, ‘I will’. But I want my father to forgive me because I could not keep that big promise to see him again. It is not my fault. It is not how I wanted our lives to turn out. In the intervening years, I flew all over the world freely, but I could not make the one journey I wanted to make more than any other, the journey home to visit him and my family. I could not even return home one final time to pay my last respects to him after his death.

This is the cruelty of occupation; this is the brutality of the colonization and this is the severe violence of Israel at all levels.

The violence and torment of Israel has caused inexplicable suffering to the Palestinian people. We have become animalized and dehumanized. My anguish and the suffering of all Palestinians in Gaza is expressed through the hieroglyphics of the flesh and biopolitics. Israel not only installed an apartheid regime in Palestine, but also uses it technological advancements and the application of knowledge to manipulate, separate and alter the human life of Palestinians, which goes beyond Habeas Viscus.

With everything I have heard, seen, tasted, felt, and lived, the pain of my life will never heal. I lost my father without seeing him for twelve years. He aged while I was not able to be there with him. I was not able to see him or touch his hands. I was not able to kiss his forehead. Israel persists with a policy of inflicting pain, which results in the traumatization of Palestinians inside and outside of the Gaza Strip. It traumatizes Palestinians who like me leave the Gaza Strip and can never return.

Through its actions, Israel seeks to ensure that the lives of Palestinians, are never without death. That our lives are never without anguish and pain. We Palestinians go beyond Habeas Viscus. Our lives have been transformed into nothingness through senseless torment and anguish both inside and outside Palestine.

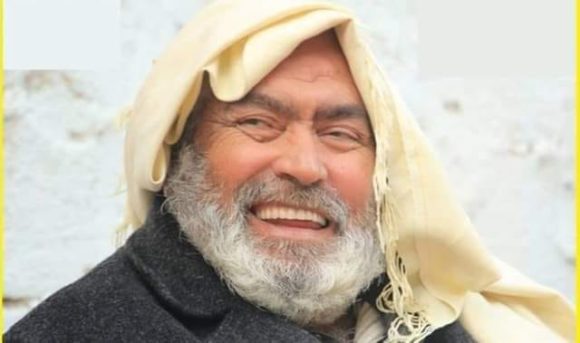

To the soul of my father, Mahmoud Alijla

Notes

1. Weheliye, Alexander G. Habeas viscus: Racializing assemblages, biopolitics, and black feminist theories of the human. Duke University Press, 2014.

2. Agamben, Giorgio. “Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life.” (1998).

3. Mbembe A (2003) Necropolitics. Public Culture 15(1):11–40

I love the photo of your father. What a handsome, vibrant man! He reminds me of many Palestinian men I have know. That “Israel” denied you the basic human right to visit him is a despicable, unforgiveable sin. My sincerest condolences.