I remember my happiness doubled when I learned I could bring one of my parents with me. I am 16 years old, it’s 2010 and I’m about to leave the Gaza Strip for the first time. I have a permit to exit from the Erez crossing in the north. I need this permit to get to the U.S. consulate where I have an appointment for an interview to get a visa. But first, I have to pick who will come with me, mom or dad?

They started fighting. Both have loads of memories and inherited memories attached to the other side of the checkpoint, the other side of Palestine. At this point I had none. I had only known growing up in a tiny corridor of land trapped with 2 million people. We call it the biggest open-air prison in the world. But outside these prison walls, is where my parents’ love story blossomed and they wanted to revisit that.

Ultimately we decided dad was a risky choice. He was previously a political prisoner, spending 18 years locked up, and we knew of too many stories of travelers whose documents were revoked because someone had been incarcerated. It was decided mom would go with me. She went to university there and hadn’t been back in 13 years.

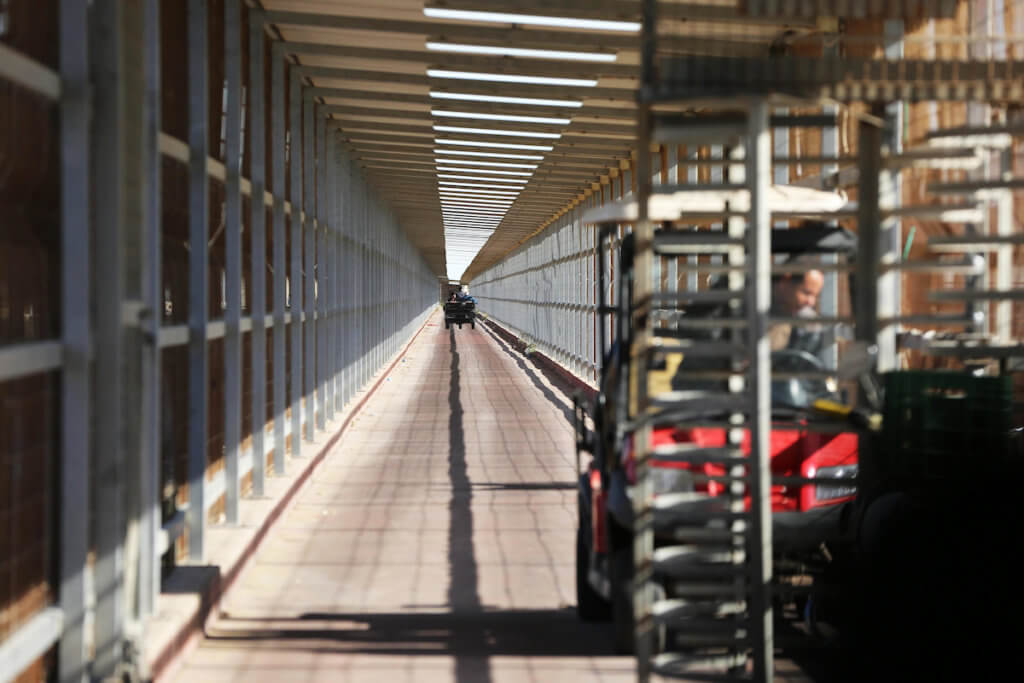

The day we left Gaza, mom and I tried to emotionally support one another. In the morning we were stressed out by the thought of going through the Erez checkpoint. To enter the checkpoint, we walked one kilometer in a narrow caged walkway until we reached the first building. This meant we were entering the Israeli military’s side of the crossing.

Once our feet stepped onto the floor, a male voice ordered mama to undress. We were alone in a room and we didn’t know the source of the voice. Our necks shifted to scan the room. Finally we saw a woman and a man in a military uniform watching us from the second floor. They continued to give us orders by speaking into an intercom in their room, and the sound amplified by a speaker down below in our room.

I exchanged glances with mom. She conveyed a sense of “all will be good” as I was looking at her and wishing I could run to hug her. We both were in the mindset that we would do anything to see Jerusalem, Jaffa, Haifa and other cities. In 2010 it was only three years after the Egyptian and Israeli siege on Gaza began. Palestinians could barely travel in and out of Gaza. That month, only 605 Palestinians were given permits to exit through Erez outside of “exceptional humanitarian purposes” and merchants. By comparison, more than 1,500 traveled out of Gaza from Erez in January before the pandemic began. Mama and I were in the distinctive position of being the only people we knew who would exit Gaza at that time.

We waited to go through a series of rooms. Our luggage was combed through and we were subjected to humiliating searches and body scans. Finally, we were allowed to leave the building. I could smell that we are not in Gaza anymore. We looked around with curiosity, fear and excitement. Everything looked different but also familiar. A Palestinian taxi driver waited for us. Mom searched for some similarities between what she was familiar with when she was living there. I also inspected the landscape, comparing it between the one painted in my head from stories told by my grandmother and other survivors of Nakba.

“There is no place like home,” is a refrain I grew up hearing in the living room of our apartment in Gaza. I associate this common saying among Palestinians most closely with my late and beloved grandmother who was born in 1922 during the British Mandate of Palestine. This was well before Zionists gangs and later the nascent Israeli occupation forces destroyed over 500 Palestinian villages during the 1948 war, which is “the Nakba,” Arabic for “the catastrophe.”

Our collective loss is mourned each year on May 15, called Nakba Day. Today, there are about 7.98 million Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons who are unable to return to their original homes and villages, of whom 6.14 million are refugees and their heirs from 1948. Palestinians mark this loss every year with pain, rage, grief and resilience. May 15 brings heavy emotions and agonizing memories.

That day I had tightness in my chest, my eyes flooded and my head filled with a marathon of thoughts.

This saying, “there is no place like home,” nurtures beautiful memories as well as the transgenerational traumas of my grandmother in Beit Jirja, where my family originally comes from. It also raises questions about the concepts of home, homeland and belonging which were distorted because I am a refugee two times over. First from Beit Jirja, which caused me to be raised in a refugee camp in Gaza, the second time in exile in Belgium as a political refugee. I moved here in 2017, at the age of 24. Therefore, I have been here for three years. I am acknowledging how fast the time passes while writing these numbers down.

Back in the taxi in 2010, having exited the Erez checkpoint moments before, I sit in the backseat as we ride past where Beit Jirja once stood. It’s only 10 miles north of the crossing.

“It looks like the European continent that I have only seen in pictures,” I mumbled to myself. Everything looks modern, very well-studied and beautifully built but on stolen lands. My eyes darted around trying to know more and to build a connection with my land that I am seeing for the first time.

We are running late, because of the strip searches at Erez, undressing and redressing, following orders from armed soldiers to go here and there. Mama and I are distressed about possibly missing my appointment at the consulate. “The route to Jerusalem takes almost two hours,” the driver tells us as we impatiently adjusted ourselves in the car.

Reaching Jerusalem, a dream destination, was the first priority. Israel seized the eastern half of the city in the 1967 war. Israelis often call the city the “united and eternal capital of Israel,” not acknowledging Palestinian rights to the land. For me and all Palestinians, it is the eternal capital of Palestine.

Because of the rush, we had asked the driver to show us Beit Jirja if we drive by it. “We will pass by it. I will inform you once we are there,” he replied.

Finally, we were greeted by a stretch of agricultural land brimming with grains along the highway.

“This is Beit Jirja. Nothing much left in there,” the driver said.

The car, which had been full of light conversation, fell silent.

He gestured toward the fields, and contradictory feelings overtook me. This was my few-seconds long first and only visit to my homeland, Beit Jirja. On one hand, it was a relief to be able to see Beit Jirja in my lifetime. I realize how lucky I am compared to many Palestinians who have never been to their original lands. On the other hand, I felt like a knife was stabbing my heart. Nothing except for some stone remnants of resilient Palestinian properties and their planted trees still standing up.

Since that visit, I was left with a condition of homelessness. I sometimes imagine a different version of Beit Jirja when I am inspired by boredom or anger. I am fatigued by hollow and seasonal condemnations from the international community, the latest over annexation, yet strengthened by a collective resilience that where there is hope justice will prevail.

This is only one story of many unheard Palestinian stories. This is also a short part of my story as a Palestinian. Today, I continue to wonder whether statelessness and exile truly deny me a home or if home is where the heart is? Maybe it is somewhere in between?