Update February 4, 2016: We have published a rebuttal to this article by Ahmad Abu Hussein, a primary source with first-hand knowledge of the subject-matter in question.

Original:

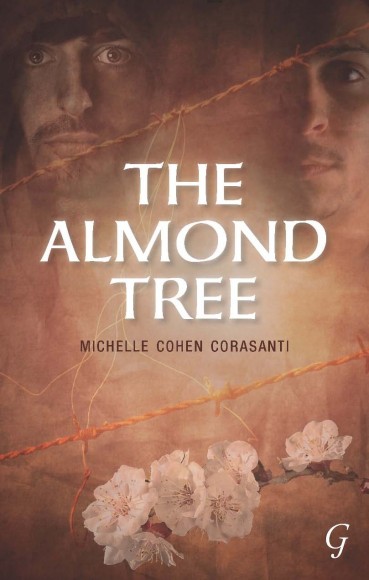

Michelle Cohen Corasanti’s response to Susan Abulhawa’s critique of The Almond Tree proves Abulhawa’s point about the book coming off as informed by white privilege and the white savior complex. Here are some of Corasanti’s major points, which need to be deconstructed:

1. Corasanti stated, “I didn’t need a Palestinian editor because I lived among the Palestinians inside the green line for seven years and saw with my own eyes the Palestinian reality.”

This is statement speaks directly to the arrogance of Corasanti that Abulhawa described. Abulhawa is Palestinian, born to a Palestinian family and raised among Palestinians in Jerusalem, in Jordan and Kuwait. Her characters were composites of grandmothers, uncles, aunts, neighbors and friends. Yet she still had several of her Palestinian friends and at least one Palestinian academic read her manuscript at different stages because she understands what Corasanti clearly doesn’t that novelists should approach the lives of others with humility. The Palestinian struggle with its many painful facets is something Abulhawa grew up with. She wasn’t an observer “on weekends” while away at school, but she still didn’t presume to fully comprehend everything her grandmother and parents told her about their dispossession and she sought to authenticate her writing from those who did. To do otherwise is arrogant and insensitive in the extreme.

2. Corasanti also said, “[Abulhawa] suggests that only Palestinians should write about the Palestinian narrative.”

Abulhawa has written favorable reviews of a Palestinian narratives by non-Palestinians. The most recent is of a book titled The Wall, by William Sutcliffe (who is white and Jewish).

3. She further stated, “I am completely mystified by Ms. Abulhawa’s criticism of The Almond Tree“.

It makes perfect sense that Corasanti is mystified by Abulhawa’s objection to the caricaturizing of Palestinians, the romanticizing of collaboration, and the diminution of the valiant Palestinian struggle over the decades. This is a textbook white privilege reaction that believes it is the prerogative of white people to fix brown lives, that nothing should be beyond their reach (not even the wounds they caused) to interpret, manipulate, pity, photograph or exoticize.

4. She then postulated “especially since The Almond Tree reaches audiences in the United States not shared widely by readers of Edward Said or Ms. Abulhawa.”

Is she really putting this orientalist novel above Edward Said’s work? Maybe not. It’s difficult to tell. But for clarification, as one of the greatest intellectuals of our time, Edward Said transformed the way in which we view the world. You cannot go anywhere in the world and not find educated people who know his work intimately. And though his work is not pop culture, it has certainly affected pop culture. As for Abulhawa, her book actually is a bestseller and has been read by millions the world over. But all that is beside the point. It’s the nature of the narrative that concerns us all, and like all people, Palestinians have a right to their own stories and they have a right to criticize and call out distortions and self-serving distortions of their lives.

5. She then stated, “Ask yourself, what is more powerful, one hundred books written by the victims of oppression describing occurrence after occurrence of loss, hardship and suffering or one book described as Kite Runner-esque and predicted to be one of the best sellers of the decade by an author perceived to be a member of the ruling, oppressor class that condemns the unjust, cruel oppression by the ruling class and extols the virtues and the legal and moral rights of the subjugated class?”

I think it’s fair to paraphrase that statement as: “Nobody wants to hear the incessant whining of Palestinians. I’m here to save Palestinians from themselves.” There are a thousand ways that Corasanti could have shown solidarity and thousands of authentic accounts by Palestinian writers that she could have championed if solidarity was truly her aim. May I suggest she and those who think like her read this excellent guide on how to check your privilege and be a true ally.

6. She then reiterated, “My protagonist would be from my friend Ahmed’s parents’ generation. What I didn’t realize was that many Palestinians didn’t know that and believed Ichmad was the Israeli pronunciation of the name Ahmed.”

So, Corasanti is actually teaching Palestinians how their names are pronounced? Further, she did not address Abulhawa’s point that the word “Ichmad” is a form of the verb to suffocate/subdue.

As a Black American, who has traveled to Occupied Palestine more than once, I not only empathize with Palestinians, but I can smell from a mile away those who attempt to transpose their narrative upon marginalized people based upon their privileged arrogance. Using literature and art that falsely depicts the realities and sensitivities of oppressed people can actually do more harm than good. I applaud Abulhawa for not staying silent in the face of such cultural misrepresentation.

I have mixed feelings about this. I haven’t read the book (it seems rather a waste of time) but assuming Abulhawa and Walid’s criticisms are accurate, I am glad they are making these points. On the other hand, at the risk of sounding condescending, the vast majority of Americans simply aren’t going to pick up and read a book by Edward Said, or probably by any Arab author . If Corsanti’s book effects practical positive change, I can’t say I have a problem with it. As the daughter of a west bank Palestinian who immigrated to the United States in his 20’s, my greatest hope is that my father gets to see the lives of his family, all of whom remain in the region, improve before the end of his life. It is certainly not ideal that Americans become aware of Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians through the writings of a western white Jewish woman, which are apparently problematic for the reasons Abulhawa and Walid discussed, but after watching my father suffer my entire life knowing what is being done to his people, I no longer care about ideals. I just want change. That doesn’t mean the criticisms of the book are not valid.

>> jenin @- December 4, 2013 at 11:35 am

Well said.

Hi Dawud!

I like the photo of you in the article.

1. I disagree that Corsanti needed a Palestinian co-editor, just as I think a white person could write a story from a black perspective, even without a black editor. But what I believe would have happened in my hypothetical is that the writer would have shared his novel with other black people for their comments, and with a sense of pride and gladness. As a result, the black people, professors, friends, etc. would have given their comments on how they thought it sounded. Perhaps Corsanti did this………………. In other words, while it is not necessary, it would happen- and with gladness- if one was trying to write from their perspective. Does that make sense?

2. It was remarkable that you pointed out: “Abulhawa has written favorable reviews of a Palestinian narratives by non-Palestinians.”

Thank you.

3. Perhaps I will be contrary, but I can see Corsanti being mystified. I could probably go through and justify main ideas of what Corsanti did and then say Susan wrote too hard a review. From the author’s perspective I can see her therefore being mystified. Corsanti could validly write a story of opposite lives- a rich person and a poor person, a collaborator and resister. (I really did not like a few things I heard though……… about a bulldozer accident……)

4. Regarding your fourth point, her statement is of course correct that her book reaches some audiences the other books do not. That is true for many books reaching audiences others don’t. I don’t think you necessarily meant it as a rebuttal, because you aid you were not sure if she was putting her book above others.

5. Unfortunately I cannot strongly disagree with your paraphrase of her statement as: “Nobody wants to hear the incessant whining of Palestinians. I’m here to save Palestinians from themselves.” What is the point of contrasting 100 Palestinians’ books with her own book?

6. I don’t really have much comment about the name thing. If she is right and Palestinians used the name Ichmad, then it is not really a major problem. On the other hand, if it’s a rare name and has bad connotations among 80% of Palestinians, then Susan’s criticism is at least a valid one from a literary point of view.

I don’t want to be too critical of such an author, it can be a good attempt or “try”, after which she could hopefully develop more in future books.

Regarding the smell test, there were some things that were the opposite of roses in her reply, otherwise there would not have been so much criticism after her clarification. Her “unlike Susan” comment was one example.

I did think she made some good explanations though, like about the sword, showing that it was a real event. Something should be said also about the fact that the author married a Palestinian. If she was only about privilege and arrogance and lack of empathy, she would not have done that for sure.

This is a problematic quote. There is validity to the notion that a non-Palestininan should tread carefully, and even a Palestininan should tread carefully, when writing about the intimate lives of Palestininas. Corsanti did come off as a bit arrogant in her reaction.

Never the less, the above attitude is problematic because of several reasons:

1. It assumes collective responsibility of white people, of which there is close to a billion on this earth, for things happened way in the past and/or for things that a very, very small sliver of a minority of white people are doing to others.

2. Converseley, just because your skin is brown, well, so is the skincolor of 4 other billion people. There’s no magic racial understanding you get because of it and to assume so is the height of not just racialist thinking, but also arrogance and myopia, the same thing you accuse Corsanti of.

3. Corsanti ultimately wanted to help Palestinians and this should be acknowledged in whatever criticism one has. You get the feeling Walid is uncomfortable with any white person, Jewish or not, writing about these issues. Well, Mondoweiss is run by white Jewish non-Palestinians. The Israel Lobby, which was the most important book in many respects in talking about the power that Israel could muster in the media and/or on capitol hill, was written by white gentile non-Palestinians. You have Max Blumenthal’s book, again the same thing.

4. Which leads me to my last point. The Palestinian narrative would never have received the attention it deserved if it wasn’t for, mostly, non-Palestinian voices in the Western world and beyond. Many of these voices, at least some of the more influential, were and still are white. There are many examples of help, direct or indirect, which if we followed Walid’s intolerant racialist thinking, would be dismissed as whites helping brown people.

So, in summary, while I agree with the notion that one should tread carefully, and certainly not react as angrily as Corsanti did when confronted with problematic issues with your work, as she did, the racial essentialism/isolationism described in this review is problematic for other reasons.

Walid may give himself the privilege to rant about white liberal activism, but if you ask the people in the occupied West Bank if they’d like to be helped in their struggle, I highly doubt they’d follow his advice of rejecting any white help out of racial identity politics. This is an example of the racial myopia that exists in the U.S. and is divorced from what needs to be done; namely raise consciousness of the issue.

So while Corsanti should be more careful in getting Palestinian perspectives in the editing process, Walid ultimately shows more of his own bigotry/racial intolerance in his reply. And he doesn’t speak for Palestinians nor does he speak for billions of brown people just because of his race, no matter how much he wishes to claim that mantle.

“Michelle Cohen Corasanti’s response to Susan Abulhawa’s critique of The Almond Tree proves Abulhawa’s point about the book coming off as informed by white privilege and the white savior complex.”

Absolutely. Reading Corasanti’s response to Susan Abulhawa’s critique, I was remined of a line from “Portnoy’s Complaint” regarding his father making “Jewish confession.” That is, the curious phenomenon of denying something while simultaneously providing enough information to essentially substantiate the critique.

Basically, we have a high-achieving Jew from a Zionist family who spent seven years going to school in Israel, the first two of which were at a Hebrew boarding school during which she had a Kahanist boyfriend. Her initial awakening seems to have occurred one summer while partying in Paris with some Lebanese elites. She returns to Hebrew University where she rubs elbows with some Arab Israelis and hears of someone named Mohammad. She becomes aware of Israeli racism. The intifada affected her. She returns to the US, gets her Masters in Middle Eastern studies at Harvard, continuing on for a Law degree and a PhD. She met her husband at her father’s law firm and lived happily for twenty years until she read “The Kite Runner” and decided that she could write a Jewish cum Palestinian version based her experiences as a student in Israel.

Had she simply written a work of fiction based upon her observations of Israeli racism and discrimination, that would have been fine (at least with me). But that wouldn’t have been the kite runner, would it? To write something comparable, she has to speak as a Palestinian victim of Israeli anti-Arab racism. Trouble is, the more authentic her account, the less literary license she can take to create her updated version of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” in Palestinian kite runner guise. Also, the less marketable her book will be. What to do?

Corasanti claims that based upon her experience she didn’t need Palestinian editors for feedback. I agree. If the goal is to overlay “The Kite Runner” onto “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” as told by an Ivy League Jew in Palestinian drag, she had ample material to work with. The key is that she wants to create a Palestinian version of “The Kite Runner,” authenticity of little moment. And since she is a successful, well-connected member of a well-known kinship group, she has had considerable initial success, her CV now even more impressive. Has she contributed to elite mythology? You better believe it. Is Susan Abulhawa justified in her critique? Surely she is. Is the system fair? Of course not.