When I think of the Gaza Strip, food is the last item on my mind. I’m usually reading about Gaza when Israeli warplanes bomb the coastal strip.

But perhaps I should think of food more often when my mind goes to Gaza, the first Palestinian territory I ever visited. Whether it’s the devastation the Israeli-imposed naval blockade has wreaked on Gaza’s once-vibrant fishing industry, or the closure of the “buffer zone” near the border that prevents farmers from reaching their land, food is a perfect window into Gaza’s plight–as well as the more positive aspects of its culture and society.

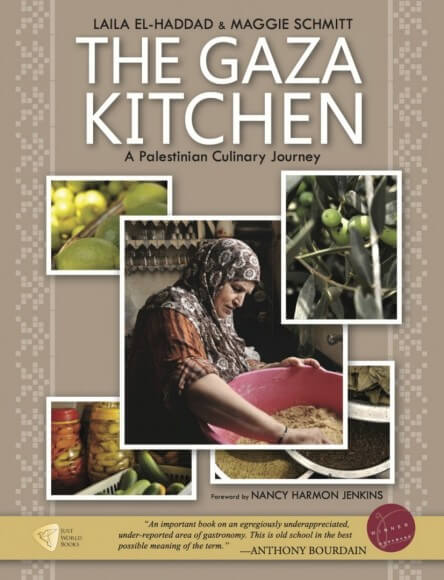

Food, and how to cook Gazan food right, is the subject of Laila El-Haddad’s and Maggie Schmitt’s captivating 2012 book, The Gaza Kitchen: A Palestinian Culinary Journey, published by Just World Books.

Last week, I had a wide-ranging conversation with El-Haddad, a Palestinian journalist who is also the author of the book Gaza Mom: Palestine, Politics, Parenting and Everything In Between. We spoke about how the cookbook came to be, her experience with celebrity foodie Anthony Bourdain and the smashing of stereotypes about women in Gaza. The interview is lightly edited for clarity.

My conversation with El-Haddad comes in the midst of Mondoweiss’ summer fundraiser. And if you donate $80 or more, you will receive The Gaza Kitchen or another great Palestinian cooking book, Olives, Lemons and Za’atar: The Best Middle Eastern Home Cooking by Rawia Bishara.

Alex Kane: Gaza is most often talked about in the U.S. as a geopolitical issue. How and why did you decide to write a cookbook?

Laila El-Haddad: Food has always been a passion of mine ever since I was a young child growing up in the Gulf Palestinian diaspora community. I was born in Kuwait, raised in Saudi Arabia, and food was always a great interest. I think part of me sensed that it was a connection to the homeland and to a dispossessed nation, and I always sensed there was something unique specifically about the cuisine of the Gaza region, because a lot of the other Palestinians in our community from different areas had never heard of the dishes that we were making, and/or my mother would not want to make them because she thought we wouldn’t like them. That piqued my curiosity early on.

As I grew older and moved around, back to Gaza, worked there for a while, I started my blog and every now and then I would blog about food-related items and people seemed interested. Something sort of clicked: this is a good–as my co-author used to say–backdoor. It’s a good way to make the issue of Palestine approachable to those who are not familiar or have animosity. It’s a way to humanize it. Everybody likes food, obviously. Food is the thing around which people congregate, conversations happen in the kitchen and around the table. That was my initial interest in it.

Then in 2007 I moved back to the U.S. and relocated from Gaza to where my husband was, and my co-author Maggie Schmitt, she lives in Spain, had been to Gaza and was writing food-related articles for The Atlantic, and she too thought food would be a good way to speak about broader issues. And the food itself, in its own right, is very distinctive. She approached me, in the course of writing an article, and had found very little written on the subject beyond what I had written on my blog. Together we thought up this idea of writing a book about the subject.

But let me backtrack. We took a gamble because we were concerned that people wouldn’t get it in Gaza. Why were we writing a book about the foods of Gaza? Though we used a documentary approach, and it’s not just about the food per se. Because a lot of times when we approached your typical human rights activist, or Palestine solidarity activist, people looked at us and said, “this seems so frivolous, why would you want to write a book about food when there’s all these greater political issues to be concerned with?” People almost didn’t take it seriously. Then on the other hand, you had the mainstream saying, whether it was publishers or others, saying, “oh, no, this is way too political. Why can’t you give us a straight-up cookbook, we don’t want something that’s politics and food.”

So we sort fell between the cracks. We were afraid going to Gaza and approaching people that we would have a problem. But to our delight, it was so easy, we could have gone on for months and months. People immediately understood it was about much more than just food. It was about writing the Palestinian narrative, being able to document their lives as human beings, and we need to humanize Palestinians. People were just ecstatic, they were thrilled to be able to share their own story that don’t have to do per se with the situation. Everyone wants to share their grandmother’s lentil recipe, or the best way to cook okra. We had more material than we could deal with. People were so hospitable to us and really let us into their lives and their homes. It was a way to broach barriers that, say, men wouldn’t have been able to, with Maggie and I being a two-women team. Or if we wanted to go in there and talk about the impact of the siege, people may have these rehearsed responses that they think people want to hear. But when we go in there saying, “no, we actually want to see you make maklouba,” so much other stuff comes along with it. In the course of making maklouba, we would hear about Um Sultan’s farm by the border that was razed by Israeli armored bulldozers two different times, forcing them to relocate, and how that impacted their lives. So you get the back stories.

There’s a lot of Palestinians who are passionate about food, and there was a smattering of books out there, but there was nothing about southern Palestine, the Gaza-area. Our intent wasn’t to play into the separation between the West Bank and Gaza, and we make that clear by saying, we’re documenting a historic region. Not the Gaza Strip per se, but the Gaza historic district, pre-1948, which extends beyond the modern-day borders of the Gaza Strip. So why Gaza? It’s partly because of what happened in 1948, when you have massive populations of Palestinians piling into that area from as far as Yaffa, from the villages in the east, from the Bedouin areas in the south, from Bir As-Saba, and then these borders are drawn around them. So it makes Gaza a really interesting place to encounter the cuisine of a much broader Palestinian area–and the histories of villages that were completely wiped off the map, that were depopulated. Often times, the only way to be able to explore this history, to live this history, is through the food you find in Gaza.

AK: What you just said about the expanded borders of Gaza, and food from Yaffa, that speaks to how food is very political, even though people don’t usually think of it in political terms. What do you think are the specific ways in which food in Gaza is political?

LH: On one hand, food is just food. I don’t think anybody thinks of it as political. At least for the average Palestinian in Gaza, food is a daily struggle for survival, it’s a daily struggle to feed your families, and that in and of itself, I like to think of it as the ultimate, daily non-violent resistance, this enduring struggle to remain human, despite all the impossible odds.

But precisely because it is a struggle, and because of the blockade, it becomes political, it is undeniably political. The Israelis politicized it because of the calorie counters. This was especially the case in 2010 when we were doing our field work. That was the year this formula was released by the Israeli army under pressure from Gisha, who took them to the high court demanding to know what the purpose of the siege was. And there were three tenets of the Gaza blockade: “no prosperity, no development, no humanitarian crisis.” What that means is you don’t want to have a situation so bad that it results in a media outcry. You want to keep them teetering on the edge, you don’t want the population to be able to prosper in any way, to have the materials and goods to be able to prosper and be self-reliant and develop. And so how do you do that? By restricting the number of calories. And it became clear that there was an equation where you allow in a certain number of goods to meet the formula they came up with to determine that this is exactly the number of calories the population needs.

In turn, what ends up happening is you have goods available in Gaza–and this is a very misunderstood area. People always assume, or equate, blockade or siege with lack of food, which is not the case. It’s actually much more sinister and depraved. They let in certain quantities of goods, depending on the time of year. But because of a siege that has caused almost universal unemployment and prevented people from being able to be self-sufficient, it has resulted in food insecurity for 80 percent of the people. The goods that are available are not accessible. It’s what known as the availability vs. accessibility paradigm. Things are available, they’re just not accessible because of the siege, which is something we explore in the book. And what we learn is that the availability of goods is determined almost exclusively by Israeli market surpluses.

So you might find bucketloads of Galangal, with which the population does not know what to do–which is a true anecdote, by the way, that we noticed there. We only discovered later that it was because there was a surplus in the Israeli market. There was a big Thai food craze that year. What do you do with the excess? You dump it in the Gaza market. So it’s actually a very fruitful, productive market for the Israelis, and the Israeli agriculturalists were the first to protest when the sanctions were put in place, because they were the ones losing out. But it’s not like the Palestinians necessarily get what they want or need or are even able to purchase, because these things are sold at inflated prices. So the blockade is very economically beneficial to Israel.

Gaza is historically a rich place. It’s not like this happened as a result of economics or natural disaster. This is actually a very studied, deliberate situation that has been created. And this is the true tragedy that the siege was intended to create: mass food dependence, impoverish the population and unemployment.

One more thing on the politics of food: When asked about the initial economic sanctions before the blockade [after the election of Hamas], Dov Weisglass, an advisor to Ariel Sharon, said the purpose is “to put the Palestinians on a diet,” but not let them starve to death.

AK: I wanted to move on to your appearance on television, on CNN, with celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain, who went to Gaza. You were his tour guide in Gaza as he did his episode on Palestinian food. How was that?

LH: It was absolutely incredible. It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I was thrilled to be able to share my home, my culture and also what’s happening with him and with the world. It was a rare opportunity. It wasn’t just, “let’s go see Gaza, and tour around.” It was much deeper than that. I think I would have been annoyed if it wasn’t. And it was completely serendipitous. They had approached me two years earlier when he was with the Travel channel, and it didn’t work out. We were still working on the book, and the second time they approached me they had moved to CNN, we had published the book, and so it worked out.

I’ve heard from so many people who are just totally unfamiliar with the situation who saw this show. For him to be able to speak about these subjects that you never hear in mainstream coverage on Palestine, about the Nakba, about the refugees in Gaza, about the blockade, about the fact that most of the population is not from Gaza, that was really important to me as well. And again, to humanize Palestinians, to be able to show people, look, they’re ordinary people with lives, families, who ultimately want to be able to live productive, full, free lives.

AK: Earlier, you mentioned how you were able to speak to many women in Gaza, and your book notes that it is women who do most of the cooking in Gaza. Is there anything about women’s status in Gaza to be gleaned from that fact, that women do most of the cooking in Gaza?

LH: There’s the public domain and the private domain. And for the most part, I would say, in the private domain it’s the women who are in charge. And everything aside, there’s always shifting cultural norms, and some of that has to do with Gaza’s isolation and how that affects things. Palestine in general has a long history, dating back to the early 20th century, of women being very active in all fields and areas. There’s a great article I found, when I was doing research, during the British Mandate, and a newspaper article starts out with complaining about Palestinian women protesting in the streets of Yaffa and riling up old men. It was very funny. But the point is they have a long and active role.

But what we learned is that there’s always more than meets the eye. You enter that private domain and the power dynamic shifts. What I also learned, very interestingly, and this anthropologist I met in Gaza last June confirmed this to me, is that villages in southern and northern Gaza tend to have matriarchal societies, or matriarchal households. And actually it is the women who are in charge here–it’s not just behind the scenes. You might have seen that in the family we visited on the Anthony Bourdain show, and who we also talk about in the book, Um Sultan’s family in the village of Bani Sayla. She is very much in charge. She owns the farm and the land and the house. She’s divided it up for her daughters, and she runs this farm and employs 30-40 Palestinians. And when we visited her for the first time for the book, her husband was the one that cooked, she gives him orders and he does everything. That really took me by surprise. That’s not as common when you go to the city or other areas of Gaza. You go in with your own stereotype and you realize every household, or area, is different.

Generally there’s this stereotype among other Palestinians that the women in Gaza are not to be messed with, which is partly true. They always warn you about marrying Gazan women.

AK: Returning to the nitty-gritty of the cookbook: most cookbooks make cooking seem easy, though I don’t think it is. Do you think cooking good Palestinian food from Gaza takes a lot of skill and practice, or do you think a novice could pick up your book and cook something great?

LH: We had this debate–Maggie and I–on whether to make this more of an anthropological study. She’s an anthropologist, and she leaned towards that–having the recipes but not make them so step-by-step that it would take away from the spirit of the book. So it was kind of a tug of war.

In the end, we decided to make it easy to follow and accessible. We opted for that because we wanted people to, yes, learn about Gaza but also to cook food. The experienced cook can figure out how to do their own thing with it, and the inexperienced cook can follow it.

AK: I have one more question. The blockade of Gaza has intensified in the past year since the coup in Egypt. Has the book gotten in to Gaza?

LH: Yes–last June, when I went to film with Anthony Bourdain, we took several of the books with us and distributed them to the people who shared their homes and lives with us, as well as some of the individuals that helped us with the transcription and translation. Sometimes I try to send them in with correspondents or journalist friends of mine or human rights workers. But now, there’s an initiative to translate it into Arabic, and there’s several publishers that are sending us different offers, with some help from the Bank of Palestine. The CEO randomly happened upon a copy in Jerusalem, he himself being a foodie. Food is a funny thing, we’ve discovered all these Palestinians excited about this topic. They offered to help contribute and publish it in Arabic.

Once that happens, it will become more accessible to Arabic-only speakers, versus now it only being in English. I was able to give a talk in the Mathaf (museum) in Gaza to a youth group there last June. And I didn’t realize, but people were so excited by this project. I think it’s something very special because Palestinians don’t frequently see human images of themselves, or narratives that they recognize, narrated by other Palestinians. Because the overwhelming majority of the news they’re hearing is about something negative or something to do with terrorism or some kind of caricatured, horrible thing.

what a fantastic interview alex and laila, i loved it. and the movie too, a surprise.

i’m really glad you wrote this. some odd stuff too:

i wouldn’t have any idea what to do with galangal, having never heard of it before.

” [after the election of Hamas], Dov Weisglass, an advisor to Ariel Sharon, said the purpose is “to put the Palestinians on a diet,” but not let them starve to death.”

To continue about this eloquent SOB that Laila mentioned, he also admitted that the whole Gaza disengagement had been an Israeli gimmick to purposely freeze the peace process and bring the Americans around to negate the Palestinians’ RoR and recognize that Israel would not return to the 67 borders. He has since become legal adviser and fixer with the Israeli government to the Masri family for the posh Rawabi real estate development project on the West Bank. Does he ever Gaza a second thought?

Back to his babbling on how Israel conned America and the world about Gaza, from Haaretz:

http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/top-pm-aide-gaza-plan-aims-to-freeze-the-peace-process-1.136686

Boring, but it troubles me that very few average Americans know about this diet for Palestinians that we American taxpayers pay for. Hopefully, the Gaza cookbooks and the Bourdain segment spread the word more. Meanwhile, for US cable TV entertainment watchers, we keep getting more film depicting Arabs in the usual negative stereotypes. These films are adaptations of Israeli films/TV series, for example, Gideon Raff’s Homefront and Tyrant.

Laila El-Haddad is a wonderful and engaging writer! The first time I encountered her work, I believe it was in the International Herald Tribune, a really interesting personal essay about passing through some kind of Israeli border or checkpoint with her baby. I thought it was brilliant the way she personalized the experience of living under the Israeli boot and really let the reader see and feel its senseless cruelty . It is still rare to find that kind of first-hand account by Palestinians in any mainstream publication. Love her work and I’m looking forward to reading the book.