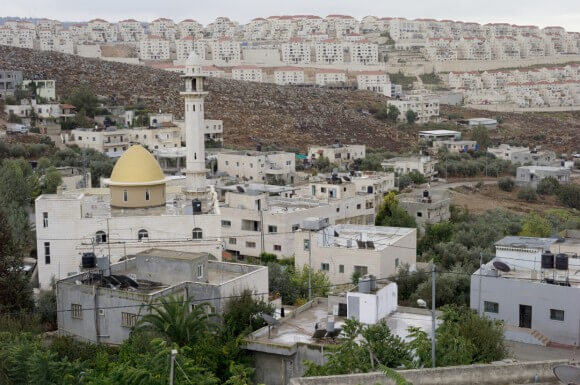

There is only one road into Wadi Fukin, a small Palestinian village with 1,300 residents, lying in a West Bank valley close to Bethlehem. The most striking part of the drive into town is the massive blocks of apartments belonging to the nearby Israeli settlement of Beitar Illit, home to over 45,000 Ultra-Orthodox Jews. The residential towers rise above the hills and slide down towards the village. The edge of the settlement is a towering wall, looming above groves of olive trees. This land, along with 370 acres belonging to the village, is now under threat of expropriation by Israel.

On August 31st the Israeli Civil Administration – a governing body that controls most of the West Bank – declared that almost 1000 acres, near the villages of Jab’a and Wadi Fukin would become state land. The announcement marks the largest attempt in decades to expropriate territory in the West Bank. Unlike recently announced building plans for Jewish neighborhoods in East Jerusalem, this move is regarded by some as an act of retaliation for the kidnapping and murder of three young Israeli Yeshiva students in mid-June and as way to link the settlement block of Gush Etzion, to the south-east, with Beitar Illit.

Wadi Fukin is a small agricultural town. It is situated on just over 700 acres of land and is squeezed in on two sides – by Beitar Illit, to the south and Tzur Hadasa, a small Israeli town just over the Green Line to the north. As the yearly olive harvest comes to a close, Palestinians here are worried they are being cut off from the rest of the West Bank and may lose the means to support themselves if their farmland is seized.

Further down along the main road – where multi-story homes give way to fields of vegetables and groves of fruit trees – Ismael Sabateen, a truck driver from the nearby village of Husan, sat on the ground sipping Arabic coffee as he took a break from picking olives with his family. “I love the olive harvest. It’s amazing to be here together in this time,” he said, gesturing to the surrounding trees. Mr. Sabateen was taking off from work for most of this month to harvest 200 trees that belong to a resident of Wadi Fukin who cannot pick the olives himself. “I come here everyday. I left my truck, my job, to come here. Working on this land is better than any job,” he explained.

Mr. Sabateen owns olive trees in his village but they grow close Beitar Illit and he is fearful of settlers throwing rocks at him and his family, so he comes here to harvest instead. The olive harvest is an important time in Palestine both for economic and cultural reasons. According to 2012 figures from the UN, 80,000 Palestinian families rely on income from the olive harvest to help make ends meet. The harvest is also seen as a month-long celebration, a time for Palestinian families to work together and reaffirm the connection they share with their land.

Mr. Sabateen was worried that this field – which is part of a swath of territory that Israel has declared as state land – will eventually be taken away. He felt powerless to do anything except come here and continue with the harvest. “We must keep and stay in the land. If you have land you have life, if you don’t have land you don’t have life.”

The valley where the village lies contains 11 springs that feed a complex system of irrigation pools that makes farming here so productive. The springs are charged by rainfall that runs down the surrounding hills but the expansion of Beitar Illit, Tzur Hadasa, and nearby Israeli industrial sites and their access roads are diverting the water from the springs.

Mohamed al-Hroub a university student from Wadi Fukin, studying geology and environmental studies at Al-Quds university, is currently researching the effects of the Israeli developments on the town’s springs. Already two springs close to Beitar Illit have run dry he said and the situation is only getting worse. “We have a spring here in the village, two months in the summer it stops. This happening because [the settlements] are taking water from the aquifer,” he explained. “If they keep building, give us until 2020 and there will be no water, no agriculture in the village and most of the people here will start moving away.”

The town’s mayor, Ahmad Sukkar, echoed this thought as he stood outside a municipal building waiting to hold a meeting with the village council. The Israelis he said, “have this plan [to make] Wadi Fukin like an island. They want to build a new settlement to the south of the village, it’s like a link between Beitar Illit and Gush Etzion,” he said referring to a small Israeli outpost called Gevaot, that would be expanded as part of the conversion of Palestinians land to Israeli-owned state land.

Mr. Sukkar complained that already, without the announcement of the land seizure, the town is left with little space to grow is being choked off. He explained that less than 50 acres of the town is zoned as Area B – an Israeli designation that denotes partial Palestinian control over land in West Bank. Most of the town, about 667 acres is Area C, which falls under complete Israeli control. If the residents want to build on this land, they must obtain a permit from the Civil Authority, an almost impossible feat. “If the people want to build in another area, area C, they stop us form working,” he said.

Inside the meeting room, council members along with landowners sat around a table with worried expressions on their faces. Some brought with them Turkish kushans – Ottoman-era land deeds – that certified ownership of their fields in Wadi Fukin. The kushans are one of the few ways residents here can hope to prevent the seizures: according to Israeli law it is illegal for land to be declared property of the state if it can be proved that it is privately owned.

Despite the fact that many residents here have kushans confirming ownership of their plots, Mr. Sukkar admitted that he was not very hopeful about the future of his village. “It’s a very bad situation,” he said, “We work in our lands everyday, we have the papers, we’re going to the court but we don’t know in the future what they will do. You know Israel, if they want to do anything they don’t care about the law, about the United Nations. They don’t care about anything, they just do it.”

Gaith Nasser, a Palestinian lawyer working on behalf of the town to appeal the expropriation order is more optimistic. Mr. Nasser has extensive experience dealing with land seizures and human rights cases in the West Bank and believes there is enough evidence to save most of the land. Reached by telephone he told Mondoweiss that, “more than two-thirds of the land that has kushans. So I think that we can prove it’s private land.”

Mr. Nasser has petitioned the Civil Administration for an extension to the 45-day limit the town was initially given to appeal the declaration. He is currently working with Mayor Sukkar and the landowners in the town to determine who has documents proving ownership of the their land and what the precise borders of those areas are.

Mr. Nasser said that the Israelis were too hasty in their declaration. He believes if they had done more research, they would have discovered that much of it is privately owned by Palestinians, and thus cannot be expropriated as state land. “They have rushed and I will prove that they have rushed in the court because all the Israeli authorities have these certificates in their books,” he said referring to a myriad of land deeds issued by the Ottomans, British and Jordanians that assert that most of the land around Wadi Fukin is privately owned by its Palestinian residents.

Whether the court case precedes through the Civil Administration’s military court or the Israeli Supreme Court the proceedings and decision-making process will likely take years to complete.

Back in Wadi Fukin a group of young residents had taken it upon themselves to stage a series of non-violent protests – similar to ones that occur each week in other small towns across the West Bank – in an effort to raise awareness about the land seizure. The protests attracted hundreds of Palestinians and international activists in the first few weeks but they soon died down and stopped altogether after a month as local residents became fearful of reprisals by the Israeli authorities.

One of the protests organizers, a man in his 20’s who wished to remain anonymous, said that the town had become divided over whether the protests were worth the trouble they could bring. “People started to get afraid for their work because there was fighting with the soldiers,” he said. “Most of them work in settlements and some have permits to work in Israel.” He explained that they were worried that they would have their papers revoked and find themselves out of work if the protests continued.

Despite this, the young man said that young people in the town were determined to raise awareness about what is happening to Wadi Fukin. “We must do something for the village,” he said, “It’s my hometown, if I can’t save it, who will? It’s our land, our blood, our soul.”

Daniel Tepper

Daniel Tepper is a writer and photographer living in Jerusalem. Follow him on twitter: @Daniel_Tepper

“We must keep and stay in the land. If you have land you have life, if you don’t have land you don’t have life.”

“We must do something for the village,” he said, “It’s my hometown, if I can’t save it, who will? It’s our land, our blood, our soul.”

I am sure that these quotes represent the feelings of many Palestinians who have already lost… this is such a powerful and moving story. Bless these determined people; I pray that they will prevail.

Thank you for this narrative, Daniel. Andrew Lichtenstein’s photos are gorgeous.

Every time I read the name of that ugly and illegal settlement, I read it as “Beitar Illicit”.

I wonder what they name the streets in that ugly concrete mass.

Do they have a Central Park or a 45th ave.

Those buildings are architecturally bland .Suits the ugly squatters inhabiting them.Netanyahu,s human shields.

What’s the Israeli word for ethnic eminent domain? Oh.. that’s correct,

until Operation ethnic cleansing commences (7 decades later)

they don’t possess any such constitution.

The buildings (settlements) are truly hideous…. architecturally, aesthetically , ecologically by the way they disconnect from their natural surrounding . A real sore to the eye !! They scream spite and disrespect of the Land .

Taxi…. you are missed.

I’m sorry, but that village is going to be destroyed. Just like hundreds of other Palestinian villages, this one will disappear.

If any other nation in the world acted in the same fashion Israel does, there would be international outcry and condemnation.

These “chosen” people are lower than low. and are not fit to be considered human.