Two months ago I went to Poland for the first time and was staggered by the erasure of Jewish life, so when a friend told me I must see the exhibit of photographs from the Lodz Ghetto at the Museum of Jewish Heritage, I made it a point to get into the city. The exhibit is overpowering, and I urge New Yorkers to try and check it out in the 10 days it is still up.

Henryk Ross was an official photographer for the Jewish Council of Lodz– the Judenrat– during the Holocaust, doing such things as producing identity photos of Jews, but he made a heroic effort to document Nazi atrocities surreptitiously and to bury his negatives in 1944 as the German occupation began to fall apart. Ross and his wife Stefania survived the ghetto and moved to Israel, where he testified against Eichmann in 1961 by producing several damning images. Though the photographer, who died in Canada in 1991 in his early 80s, said that he did not take another picture after the Holocaust.

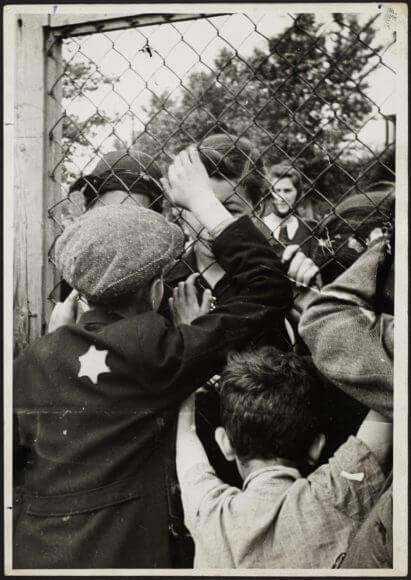

That’s understandable. The most disturbing photographs he made were of Jews being transported out of the ghetto, bound for the extermination camp in Chelmno. Jews move in a great orderly mass in one photograph, they are horse-carted in another, herded by policemen in another, forced at gunpoint on to train carriages in another. Surely the most upsetting photograph in the entire exhibit is of a mother speaking to her two sons from the central prison in the ghetto, prior to her deportation. What a nightmare world is conveyed in this half-seen face.

The photographs are accompanied by oral histories curated by the Museum, of three Jewish women describing their efforts to escape the transports. As someone who has come to this historical material late (the pressure from my community to immerse myself in the record of suffering when I was young sent me running the other way), I find it paralyzing and exalted.

This exhibit is so simple on the one hand, and so loaded on another, that in the day since I’ve seen it a lot of unintended thoughts have crept into my mind. The show is simple because it treats Ross as heroic full stop, and loaded because so many of Ross’s actions document the lives of the Judenrat. We see a lot of happy Jewish policemen in these photographs, like the image now famous below of a policeman and his wife and child. These policemen were of course serving the Nazis. These policemen conducted the terrifying roundups of Jews that led to the Nazi “selections,” documented by the photograph of the mother at the prison fence.

There are several pictures of Chaim Rumkowski, a businessman and the head of the Judenrat, who famously called on the Jews of the ghetto to “give us your children,” so they could be transported. Not long before he was himself transported to Auschwitz in August 1944, where inmates beat him to death.

The museum helpfully includes copies of hateful orders from Rumkowski that were posted in the ghetto, but underplays how terrible a man he was.

The unintended thoughts I’ve had are of how much acceptance any people can have of terrible injustice. I believe it’s in our DNA, as highly socialized creatures: we can go along with the worst crimes if there are authority figures saying that it’s all for the good of society. There is a lot of evidence in this show of people accepting the hateful as normal. For instance, there is a sign on a street adjacent to the ghetto declaring that it is verboten to Jews. There are the elaborate pedestrian bridges the Nazis created to connect disparate parts of the ghetto, over “Aryan” streets. And everyone just treats it as the way of the world. Of course that includes the Poles who went along with the Nazi occupation, too, but many Jews were complicit, or passive, and caught by Ross’s lens.

No wonder that I have been reading memoirs of Warsaw ghetto resisters: the Jewish heroes who responded to the transports by instructing Jews that the Nazis were lying, the trains were taking them to their deaths, and who began assassinating the worst Jewish policemen in 1942, and trying to kill corrupt Judenrat officers too. (Many of the Jewish policemen and even Judenrat officials were sympathetic, or tried to help other Jews.) The resisters were the exception, in that age and in ours.

The other shadow over this exhibition is the life of Palestine, which figured as a refuge for so many of the survivors of the Holocaust, including Henryk and Stefania Ross. I understand that; and while my heart is with Marek Edelman and the others who chose to remain in their homeland and carry on Jewish culture, I can blame no one for leaving Poland. What is alarming about the Henryk Ross archive is that within a few years of these frightful scenes in European cities, Jews were forcing Palestinians out of their villages and cities and ghettoizing those who remained. That is the great puzzle of Jewish political life today, which bedevils millions of people, from American Jewry to Palestinian refugees: how and why did this come to pass? I recognize that such questions are not easily addressed by museums; because these matters are current and fraught, with very much at stake right now; but the problem is plainly rooted in Europe many decades ago, and if we make an effort to study and remember the fate of Polish Jewry, as we should, it is just as important to picture the Nakba.

Thanks for this essay on a question worth reflection. Robert Sapolsky’s “Behave” tries to explain what he knows about human behavior, which is a lot. It includes a chapter on the genocide in Rwanda. It’s worth reading. Yet to me it seems more like a collection of facts than an answer. Some realities seem incomprehensible.

RE: “The most disturbing photographs he made were of Jews being transported out of the ghetto, bound for the extermination camp in Chelmno. Jews move in a great orderly crowd in one photograph, they are horse-carted in another, herded by policemen in another, forced at gunpoint on to train carriages in another.” ~ Weiss

■ Holocaust trains

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

CONTINUED AT – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocaust_trains

If Philip Weiss felt the need to tell us about Rumkowski, surely another line or two should have been added to the article in order to explain the full circumstances of his horrifying speech in the Lodz Ghetto (“give me the children”). Rumkowski thought that he could delay what the Germans called “the liquidation of the ghetto”, thus enabling the ultimate rescue of most of the residents (if the war came to its end in time). Indeed, the Soviet army had advanced to within 90 kms of Lodz by 1944, but unfortunately the Soviets did not continue on to Lodz until January 1945. Had the Soviets entered the city in the summer of 1944, we would surely think quite differently about Rumkowsky today. Lodz, the last ghetto, would have gone into history as the only ghetto that avoided the fate of all the other ghettos. Adam Cherniakov in the Warsaw Ghetto committed suicide when he was instructed to hand over the children, and this choice of action makes more sense to us today. Who knows what was the right course of action in the impossible circumstances of the Holocaust?

If Philip Weiss mentions in his article the “memoirs of Warsaw ghetto resisters” that he has been reading, surely a few lines could have been added to the article telling us a bit about them. I understand that in an anti-Zionist publication it is really impossible to say something that might be understood as praise for Zionism, so I volunteer to inform the readers that the Jewish Fighting Organization was organized by the Zionist youth groups. In the beginning, the anti-Zionist Bund was disinterested in joining the Jewish Fighting Organization. The Bund defined the Jews as a nation (just like the Zionists), and they believed that the struggle against the Nazis should be “international”. In other words, the Poles (a nation) should fight together with the Jews (another nation) against the Germans – and that would be an international struggle. Eventually, the Bund understood that the Jews are alone – and they agreed that the uprising will have to be a “national struggle” (the Jewish nation alone), and they joined the Jewish Fighting Organization. Marek Edelman, mentioned in the article, became the second in command of the uprising (representing the Bund), but the commander was Mordechai Anielewicz of Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair youth organization (representing the Zionists).

It’s interesting to point out that the vast majority of the Jews of Poland – the Bund and the Zionists – saw themselves as a national group. They were Polish citizens, but they saw themselves as a national minority group within Poland. A lot of people here present a case that being Jewish is about religion, but this is not the perception of the Yiddish-speaking Jews themselves. Interestingly, even the anti-Zionists perceived their Jewishness as a national identity (they were anti-religious).

Finally, the last paragraph doesn’t actually draw a comparison between the Holocaust and the conflict between Jews and Arabs. However, there is an attempt to make some sort of connection without actually defining what that connection might be. There is no connection.

Zionism and its spawn, the entity known as “Israel,” are a betrayal of Judaism and the six million Jews who perished at the hands of Germany’s Third Reich. As the Nazis subscribed to the “Aryan Myth,” Zionist Jews believe they had/have a “God given” right to “return” to what they erroneously believe to be their “home land” and dispossess, expel, torture, slaughter, oppress, imprison without charge the indigenous Palestinians and subject them to collective punishments and ghettoization, e.g., the Gaza Strip, the world’s largest outdoor prison.

You are really in the zone on this topic, Phil.

Best work/trip I can recall.