In a recent Zoom meeting sponsored by the Voices from the Holy Land Film Salon to discuss Sut Jhally’s film The Occupation of the American Mind, the two panelists, current and past journalists, were asked by the moderator, Diana Buttu, what term they use to name the struggle for justice in which they are engaged. Both responded, somewhat diffidently, that “conflict” is the journalistic shorthand used for this topic.

Comments from audience members then flooded the chat with many alternative terms used by allies in the Palestinian solidarity struggle: settler colonialism, ethnic cleansing, Occupation, sociocide, Apartheid, and incremental genocide. Several comments avowed in a confessional tone that the writer had seen the light and would never use the too-mild term “conflict” again.

Variants of this conversation occur often in circles where Americans are trying to find their place in the struggle for justice in Palestine. But here are some questions and comments that do not seem to crop up and should do so.

To whom are we speaking and for what purpose?

If we are engaged in a purely analytic discourse, then settler colonialism – a term first applied to Palestine/Israel by French historian Maxime Rodinson, and elaborated by Patrick Wolfe – is likely the most insightful and inclusive term. Further analysis within this framework might note that early Zionist settlers first attempted ethnic cleansing by military means, as detailed in the work of Nur Masalha and others on the Nakba (and acknowledged even by Zionist apologists like Benny Morris). Military expulsion was followed, in time, by Occupation, and within the Occupied Territories, by a regimen that one Palestinian political scientist, Saleh Abdel Jawad, has labelled as sociocide. Sociocide proceeds partly through Israel’s use of legal instruments which explicitly and systemically differentiate the rights of Jewish citizens of Israel from inferior rights held by Palestinian citizens of Israel, military rule imposed on stateless Palestinians in the Occupied Territories, and a permit regime applied to Palestinians in East Jerusalem. These oppressive distinctions satisfy the legal definition of Apartheid. However, sociocide, a broader term, also names other instruments – confiscations of land and financial assets, unchecked settler violence and property damage, harassment at checkpoints, disruption of schools, limited access to health care, and many other forms of psychological warfare – which, together, constitute a Plan B of ethnic cleansing; in the words of Jawad, an attempt to get Palestinians to leave by other means. And finally, documentation of successive waves of massacres in Gaza give rise to the possibility of an incremental genocide, a term introduced by Ilan Pappe and Naim Ateek, especially when coupled with the intense environmental degradation also produced by Occupation and documented in UN reports.

All of these terms thus have analytic merit and can be used to apply to the entirety of the Palestinians’ struggle for their rights or to specific aspects or phases of it.

However, if our purposes are political, then we cannot forget the first rule of organizing: you have to meet those whom you would persuade “where they are.” For that purpose, insisting on terms like settler colonialism or ethnic cleansing is an overreach for many audiences not already steeped in the discourse. People new to the topic need a term that leaves more room for exploration and learning.

Nevertheless, we should examine the specific objections to the term “conflict” to see where we can strengthen our case. Some see the term “conflict” as too weak, easily dismissed either because conflicts are allegedly universal or because this particular one is deemed insoluble. “Conflict” also can create false parity between a country enjoying unlimited American diplomatic, military, and economic support and a stateless people more than half of whom are refugees.

These are, indeed, pitfalls to be avoided. And yet, I would argue, use of the term conflict can also open the door to the very conversation we need to have with people new to the issue. Asking “Who are the sides” allows us to talk about the context and intent of Zionism, and the way it disregarded the rights of Palestinian communities residing in the lands it craved.

It also allows us to talk about the sadly neglected topic of Palestinian resistance and steadfastness (sumud).

Almost all of the framings preferred to the term “conflict” exaggerate its greatest flaw: telling the story as one of Zionist agency and Palestinian victimhood. Indeed, in America, nearly every conversation about justice for Palestine depicts a battle between good Jews and bad ones. If you are a Zionist and AIPAC speaks for you, then the good Jews are the colonizers and the bad Jews are the traitorous supporters of BDS. If you advocate equal rights for all, then the reverse is true: the good Jews are those who do witnessing trips to Palestine and support the boycott, while the bad Jews are those who misuse Holocaust memory and who weaponize charges of antisemitism to avoid confronting Israel’s human rights violations.

But in both of those stories, the Palestinians are all too often reduced to being silent victims. A conflict, especially an asymmetric one, opens the door to incorporating Palestinian resilience and popular resistance into the narrative.

This is not an argument about the exact words we should use in advancing the struggle for justice in Palestine – inevitably those will change with context and with time. Rather, the argument here is about attitude. Radical purity is of no use to the movement; showing off, condescension, and intimidation never won hearts or minds. Political effectiveness and intellectual integrity, on the other hand, are both necessary standards. Our work is to tie them together, to make the case that brings newly engaged people from “conflict” to settler colonialism, and onwards to strategic social and political action.

Good article with good points. The next step would seem to be figuring out how to get people from “conflict” to “settler colonialism”. What works, and what’s counterproductive? What’s needed for different types of audiences?

1 of 2

The Anti-Semitic Birth of the Zionist State: A History of Israel’s Self-Hating Founders | Defend Democracy Press

“The Anti-Semitic Birth of the Zionist State: A History of Israel’s Self-Hating Founders” by Miko Peled, March 17/21

“When the victims of Zionism finally have their day in court, the world will see just how cruel and racist the early Zionists really were”

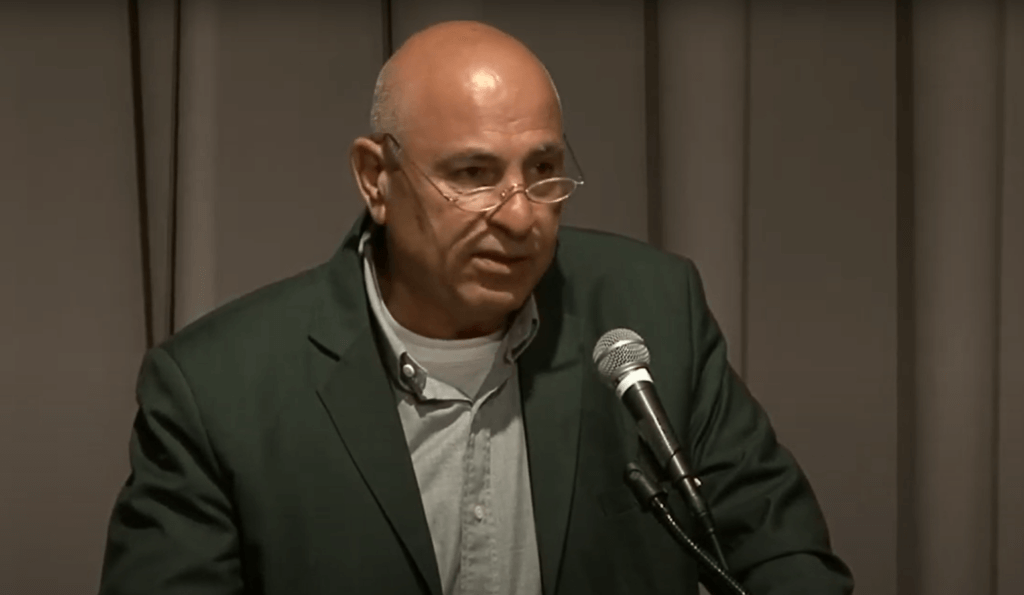

by Miko Peled, March 17th, 2021

EXCERPT:

JERUSALEM — ‘Self-Hating Jew’ — along with other terms like ‘traitor, Zhid, Kapo, Nazi, and Little Jew’ — are among the epithets used by Zionists to insult Jewish people who oppose or reject Zionism and its racist ideology.

“A recent episode of Rabbi Yaakov Shapiro’s podcast ‘Committing High Reason’ recalls the history of Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism and of the Zionist State, and sheds new light on the term ‘Self-Hating Jew.’

“Committing High Treason

Rabbi Shapiro sources all of his claims methodically and when one hears what Herzl, who was Jewish himself, wrote about Jewish people, the only conclusion is that he was the quintessential ‘Self-Hating Jew.’ There can be no doubt that he hated Jewish people and wanted nothing more than to dissociate himself from the ‘common’ Jew. Furthermore, he was not alone: other Zionist leaders — Vladimir Jabotinsky, Chaim Weizmann, and others — were equally openly hateful of their Jewish brethren.

“In 2018, Rabbi Shapiro published a 1,400-page book titled “The Empty Wagon, Zionism’s Journey from Identity Crisis to Identity Theft.” The book outlines the vast differences that exist between Judaism and its main nemesis, Zionism. The book was written for Orthodox Jews and indeed every Orthodox Jewish home I have visited in the last two years had a copy of this massive work. Even though it assumes a great deal of knowledge about Judaism, the book has an unprecedented amount of well-sourced information, so that even those of us who are not well versed in Judaism can learn a great deal from it.” (cont’d).

.

2 of 2

“The information presented in this particular episode of Rabbi Shapiro’s podcast can also be found in his book, and it leads to the undeniable fact that the founder of Zionism — and many of his contemporaries — hated everything about Jews and Judaism and hated the fact that they themselves were Jewish. According to Rabbi Shapiro and many other Orthodox rabbis whom he quotes, it was their hatred of Jews and not their desire to save them from anti-Semitism that was the driving force behind the creation of Zionism and the establishment of a Zionist state.”

“The founder of Zionism not only believed that the anti-Semitic trolls about Jews were true, but also justified them. He claimed only that these racist accusations applied to the ‘other’ Jews, those who were not as secular and ‘enlightened’ as he.

“The story of Herzl, as it is told in Zionist schools both in Israel and around the world, makes him seem like the savior of Jews, a man motivated by the desire to do good. However, a more in-depth look into the man and his motivations reveals that he despised Jewish people and wanted to separate himself from ‘common’ Jews by creating a space, an existence for people like himself who were Jews by birth but despised what it means to be Jewish.

“Vladimir Jabotinsky, the father of right-wing Zionism and today’s Israeli Likud Party, was another classic case of the ‘Self-Hating Jew.’ He wrote that ‘[t]he Jews are very nasty people and their neighbors hate them and they are right.’ “

It’s not necessary to use abstract terms. It may be better to avoid them. But the basic underlying reality is actually very simple. It gets overlaid by and lost in all the complex detail. That reality is that a movement arose among one group of people to settle in a country inhabited by another group of people, get rid of them, and take the country over. It has been a long-drawn-out process using various means. But that is the crux of the matter. It is what always needs to be explained, to all but the best informed of audiences, because most people rely on the corporate media for information on foreign affairs and the corporate media never mention it. When you grasp it for the first time, you are astonished and all the confusing details suddenly make sense.

“All of these terms thus have analytic merit and can be used to apply to the entirety of the Palestinians’ struggle for their rights or to specific aspects or phases of it.”

“UK publisher altered school textbooks in favor of Israeli regime: Report

The academics said in a report that the London-based publisher had made hundreds of changes to two GCSE textbooks used by UK high schools and distorted the historical record related to the conflict between Israel and Palestinians in the occupied territories.

The books, titled Conflict in the Middle East and The Middle East: Conflict, Crisis and Change, both by author Hilary Brash, are read by thousands of GCSE and International GCSE students annually.

The report, written by Professors John Chalcraft and James Dickins, Middle East specialists and members of the British Committee for the Universities of Palestine (BRICUP), found hundreds of changes to the textbooks, averaging three changes per page, that included alterations to text, timelines, maps and photographs, as well as to sample student essays and questions.

Highlighting multiple changes to the books, the report said the alterations had been made after an intervention by the Board of Deputies of British Jews working together with UK Lawyers for Israel (UKLFI).”

https://www.presstv.com/Detail/2021/04/02/648582/UK-Pearson-GCSE-textbooks-Israel-Palestinian-conflict