I grew up in a village called Kobar. It is known for many things, some funny and even sarcastic — like the groom who got scared and ran away on the night of his wedding.

But one thing we all took pride in was that our village had many freedom fighters. Most of them were behind bars, but we knew their stories by heart, even though some had been arrested in the early 1990s before we were even born.

We learned about them from our parents, grandparents, friends at school — basically in every social setting.

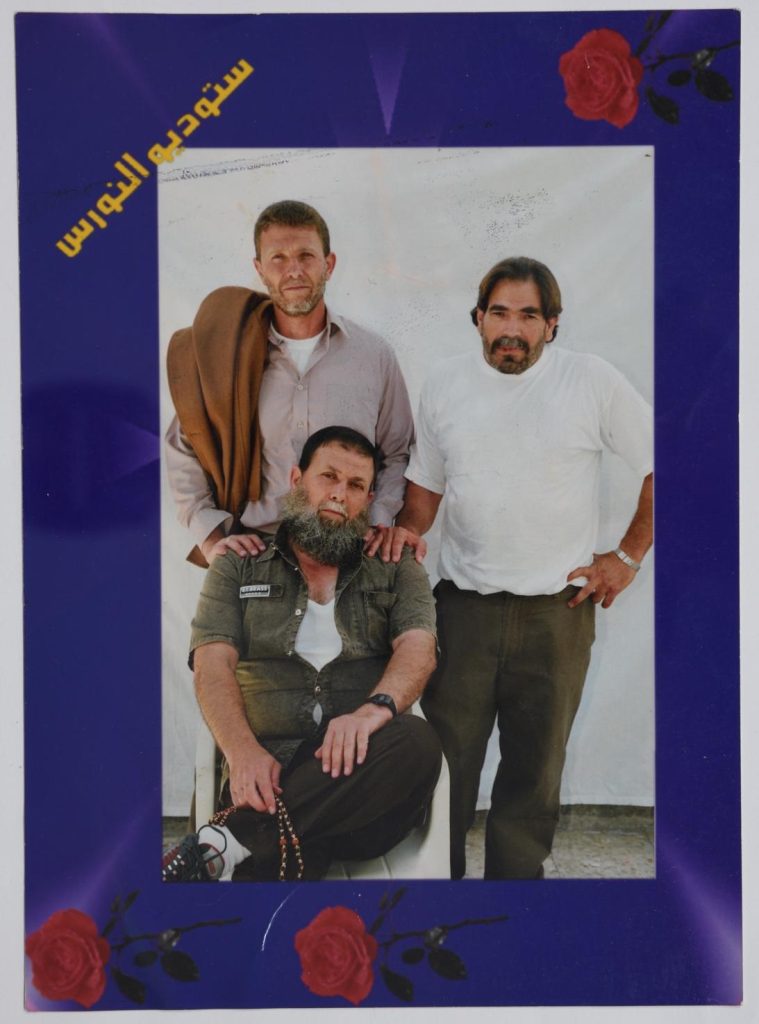

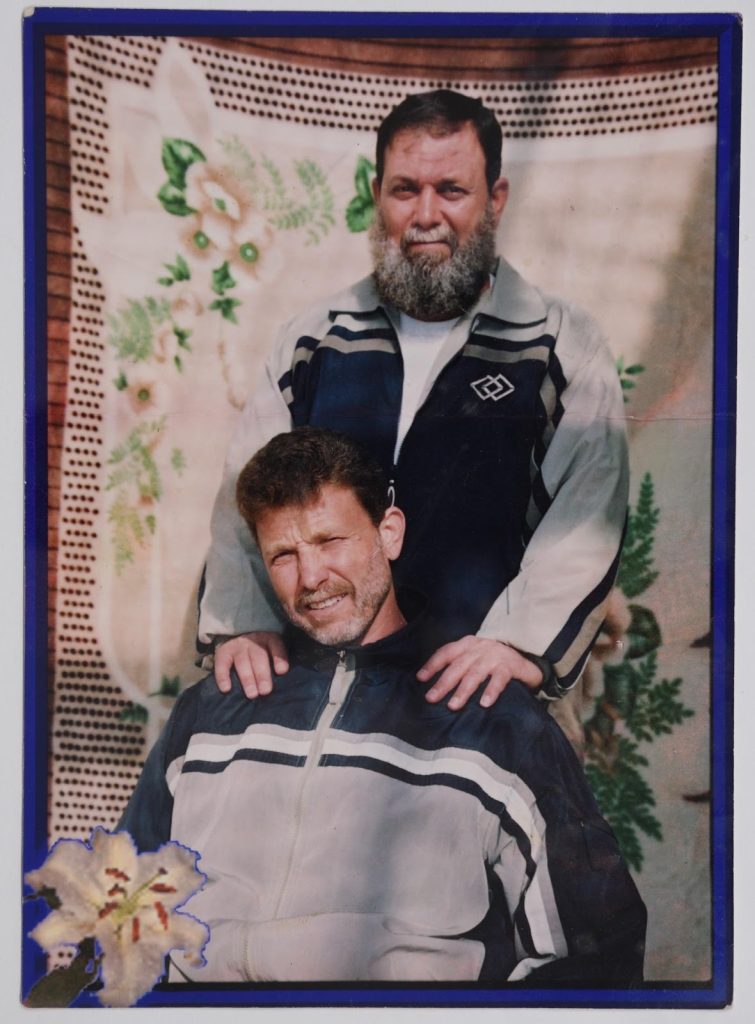

Among them, Nael and Fakhri al-Barghouti stood out the most. They were cousins, both accused and sentenced to over 80 years in Israeli occupation prisons.

One story that my mother told me at an early age, and that has stayed with me ever since, was about Nael al-Barghouti’s mother.

“She was a mighty lady, fearless and resilient; mashallah. Two of her sons were imprisoned, Nael and Omar (Abu Asef),” my mother would say before continuing the story. “And she never missed a chance to visit them when she was allowed. Like always, the occupation officers at the prison would give the families a hard time, but she never let them break her spirit.”

On one of those visits, a soldier called her name, twisting it as an insult. Her name was Farha, which means “joy” in Arabic, but he deliberately mispronounced it as “Farkha,” which means “chicken.”

Farha got up, looked him in the eye, and said, “You called me chicken? Thank God I gave birth to roosters who will pick your eyes.”

That story still circulates in the village as a testament to her strength. “A mother with such resilience could only give birth to fighters like Nael and Omar,” people would say.

In 2011, after 34 years in Israeli prisons, Nael was released in a prisoner exchange. The entire village celebrated. Most of us had never seen him before, as he had been imprisoned before we were born.

That day, after a long celebration, the crowds that had come from outside the village began to leave. I finally got to see Nael up close; he was being interviewed by an Israeli news channel.

He was in his 50s at the time, but despite spending 34 years behind bars, I will never forget the energy he radiated, of a man reborn to fight.

“As long as the occupation continues, we will keep fighting,” he told the reporter.

Then, in Hebrew, he said something before switching back to Arabic:

“I know your language. I learned it in prison. But I will speak to you in my language.”

For weeks, he was the talk of Palestine and the village.

Rumors spread about how, while in prison, Nael had fallen in love with a woman he had never met. He had heard her voice on the radio, defending Palestinian prisoners, advocating for their rights, and visiting their families, including his own parents.

She herself had been imprisoned for 10 years. Her name was Iman.

When Nael was freed in 2011, the village buzzed with debate. Some said his family was pressuring him to marry a woman who could bear him children because Iman could not. Most people agreed — he should marry someone who would give him children. But others argued that this was a true love story, and Nael would never walk back on his word.

Less than a month later, Nael married Iman.

All of Palestine celebrated.

On their wedding day, Nael stood before the crowd and said:

“As a freed prisoner, I consider my marriage to another freed prisoner a victory against prison, a challenge to those who deprived us of our freedom, and a triumph of the spirit of faith and hope. This joyous occasion is only the first step in unlocking the door to the life that still lies ahead of us. They denied us freedom, but they did not kill our determination to break our chains. Now, I can say that Iman and I will embark on a new journey, as we are about to start yet another family among others in this great nation. We pray to God that He completes our happiness and joy and heals our wounds that have bled for too many years, leaving deep memories that will live with us forever. But these memories shall also serve as lessons that will strengthen our resolve to continue our march for freedom.”

Nael and Iman moved into their home on the eastern side of the village, on a hill that overlooked the surrounding lands. Almost every day, Nael hiked through the fields, reconnecting with the olive trees he had tended to as a young boy before his arrest, some of which he had planted himself and that now bore fruit.

In May 2014, I moved to the U.S. for school in Chicago.

One day, I was on the phone with my father, who was working at the swimming pool our family owns in the village not far from Nael’s house.

Suddenly, I heard my father call out to someone, “He’s stubborn! Keep your eyes on him.”

“Who are you talking to? And who’s the stubborn one?” I asked.

“Nael Barghouti. This guy doesn’t sit still. Mashallah, his soul is younger than a 25-year-old’s,” my father said.

Nael had been hiking through the mountains, collecting sage, and had stopped by the pool to cool off. He wanted to swim. He told my brother, Omar, who was the lifeguard, and tried to warn him that the pool was deep:

“I learned swimming 34 years ago in the natural spring (al Hawooz), you were not even born! Don’t try to save me if you see me struggling. Only save me if I stop moving.”

Moments later, I could hear men in the background cheering him on.

“He made it across,” my father said.

After his swim, Nael dried off and went straight back to the mountains to continue his hike along with a bag full of sage. Omar still recounts the story to this day.

But just a month later, on June 18, 2014, my father told me on the phone: “The Israeli occupation re-arrested Nael.”

They had ordered him to keep to himself, to stop being active in the community. He refused. He wouldn’t miss a chance to advocate for Palestinian unity and the rights of prisoners.

At first, they placed him under administrative detention for 33 months. Then, they reinstated his original life sentence, plus 18 years.

The entire village was devastated.

On that same call, my mother said, “They’re saying he sent Iman a letter, telling her he was giving her the freedom to walk away because he didn’t want to make her wait for years again.”

Then, after a pause, she added, “But she refused. She said, ‘I will wait my whole life. I will keep fighting for him till the end.’”

Today, Nael is set to be free again.

As part of the recent hostage exchange, he is expected to be exiled to Egypt, for now.

His wife, Iman, tried to leave the West Bank to meet him there upon his release, but the Israeli occupation denied her exit.

I can’t help but ask myself: does the reunion of two true lovers scare the occupation that much? Do they think they can break them?

They are delusional.

Nael and Iman will forever be the perfect fighters and lovers.

Hareth Yousef

Hareth Yousef is a Palestinian photographer, documentary filmmaker, and educator. He is the Brock Family Visiting Instructor in Studio Arts at Duke University, specializing in photography, documentary filmmaking, and moving image practice. Born and raised in Kobar, Palestine, Hareth’s work explores identity, memory, representation, and place, with a strong focus on Palestinian narratives. His creative practice bridges visual storytelling and cultural history, emphasizing the interplay between the past and contemporary struggles. Hareth holds an M.F.A. in Experimental and Documentary Arts from Duke University, a B.A. in photography from Columbia College Chicago, and a degree in journalism from Birzeit University.