A decade ago I was on a speaking tour in Washington DC with Husam el Nounou, administrative director of the Gaza Community Mental Health Program. I will never forget while exploring the National Museum of the American Indian, he suddenly left in tears. As we stood in front of the large stone edifice he explained this is what he fears for Palestinians, that we will mostly know their culture and history through static dioramas reflecting a reality that exists only in the past, while the remaining population is left to eke out a desperate existence living on reservations.

More recently Bshara Nassar whose family founded the extraordinary Tent of Nations near Bethlehem in the West Bank, also arrived in Washington DC to work on a master’s degree in conflict transformation. He noticed the numerous museums dedicated to recording the history and culture of oppressed peoples, the National Museum of the American Indian as well as the Holocaust Museum, Laogai Museum, Women in the Arts, African Art, etc. In this city where the powerful narrators of human history collect and frame the cultural and historical bits and pieces that shape official memory, he realized there was no space for Palestinian stories. He noted a deafening absence of his own family trauma, the experience of the Nakba, Arabic for “Catastrophe,” referring to the loss and dispossession of the indigenous peoples that began in 1948 with the founding of the State of Israel.

A team of Palestinian and Jewish-American artists, (“a passionate Palestinian” and “a well meaning Jew”), joined Bshara to organize, fundraise, and launch the first in the world Nakba Museum Project of Memory and Hope. They chose to focus on the 750,000 people originally displaced from their homes in historic Palestine and their five million descendants, UN registered refugees living the consequences of that expulsion in nearby villages, cities, refugee camps, and the Diaspora.

On June 13, 2015, the humble but deeply aspirational two-week exhibit opened at the Festival Center in Washington DC. The exhibit features large, beautifully rendered panels (produced by a German group Fluchtlingskinder im Libanon e. V., a charitable organization dedicated to aiding Palestinian refugee children in Lebanon), each focusing on different fragments of history. The panels start before 1917, moving sequentially up to today, explaining important United Nations Resolutions, and the human consequences of this complex and tortured saga. The sections encompass factual texts, excellent maps, evocative historic photos, and personal narratives to present a compelling and accessible account. Some of the material is from the Israeli organization Zochrot, Hebrew for “Remembering,” that researches the destroyed Palestinian villages in Israel and brings this information and the painful questions that arise to an ambivalent and largely ignorant Jewish Israeli public. But this is not only a tribute to a past that has been made invisible; there are also a series of panels with narratives and photos of today’s refugees, living in camps from Lebanon to cities in Germany, making these stories personal, real, and compelling.

The exhibit also features poetry, stories and paintings by Palestinian refugee artists curated by a painter from the Dheisheh Refugee Camp in Bethlehem, Ahmed Hmedat, who recruited other Palestinian artists and helped to assemble their work for display. Near that exhibit are stark and gorgeous photographs exploding with the harsh realities of the Israeli occupation and the beauty and bounty of the land, and video interviews of Palestinians telling their Nakba stories, taken from my documentary film project, Voices Across the Divide. The paintings depict both metaphor and reality; ruthless austere landscapes, walls, guard towers, children playing in the concrete jungles of the refugee camps, and the powerful yet ephemeral dream of return.

People nibbled on humus, sipped wine, networked, hugged, and absorbed the power and message of the exhibition. Bshara spoke briefly: “For too long our story was silenced, trapped in the politics of power… no one can tell our story for us.”

He seeks to create a safe place where these stories can be told and heard; “not just about the past, the past reaches into the present.” He wants to be clear this is “not a victim story,” not a story about political arguments or religious conflict. He is “here to tell the human story, this is what we are all about with all the complexities and contradictions, tragedy and courage. A story of hope that refuses to give up.”

He wants to create this process of bearing witness through art, creativity, and dance, and stresses this is only the beginning. “The story is the land and the land is the story.” He reminds us that the Nakba is ongoing and education and deep reflection are critical to understanding, compassion, and celebration on a global level.

While Bshara insists this is not a political project, many scholars and activists have explored the concept of “memoricide” (Ilan Pappe) or “sociocide” (Eve Spangler) as it relates to the absence of the Nakba in the telling of modern history. It is clear that we can only know the past if we have the stories and the evidence; thus the erasure of the memory of certain experiences as well as the re-interpretation of said memory is critical for our understanding as well as our misunderstanding of history and our ability to move forward towards conflict resolution. Within this struggle this erasure occurs in the context of Israeli nation building, territorial expansion, racist attitudes towards the “other,” justifications for military and state behaviors within a certain framing such Biblical promises, the Nazi Holocaust and permanent victimization, “Hamas is ISIS and ISIS is Hamas,” etc.

This deliberate state-sponsored erasure of Palestinian voices and the evidence of their centuries old existence thus constitutes a form of historical genocide, of attempting to destroy the memory of a people’s history and thus the people themselves. I suggest that refusing to forget is thus a deeply political act.

I drive by the impressive National Museum of African American History now under construction with an evocative bronze metalwork façade. The building shimmers with an African rhythm, grounded in Yoruban art and architecture, a testimony to the centrality of African Americans in the history of our nation and the critical importance of acknowledging the generations of slaves, their descendants, and their rich contributions to the history and culture of the United States. My thoughts drift back to the Nakba Museum and the critical importance of acknowledging that history for Palestinians as well as for Israeli society, American Jewry, and the US public.

I try to imagine studying US history and omitting Native Americans, slavery, Japanese internment, the McCarthy era, mass incarceration of black men, all the ugly injustices, prejudices, and power disparities that are part of the uncomfortable process of nation building and the continuous struggle to create a democratic and tolerant society.

Like Palestinians, the Nakba Museum Project of Memory and Hope is filled with loss, trauma, resiliency, and beauty, and like the people it is celebrating, deeply in need of a welcoming, permanent, and tolerant home.

For more on the Nakba Museum, see this piece we published last week. –Ed.

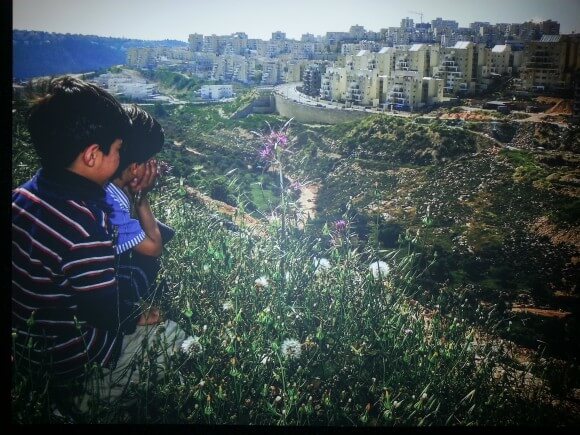

The picture of the two little boys looking at illegal settlements is so telling. It shows just how hopeless it must be to be young and realize there is no hope for them to live normal lives, own their own space, and flourish as a people. There are generations of Palestinian kids who have known only what life is living under a brutal occupier, have guns pointed at them, seen their family members brutally killed, and have no freedom to move around like most human being do.

Congratulations to all to worked on this project. It helps to have a special museum so that the world can know the facts about the plight and history of the Palestinians.

A small exhibition lasting 2 weeks, which I expect no political leader will visit! A whistle among trumpets.

“This deliberate state-sponsored erasure of Palestinian voices and the evidence of their centuries old existence thus constitutes a form of historical genocide, of attempting to destroy the memory of a people’s history and thus the people themselves. I suggest that refusing to forget is thus a deeply political act.”

Perfectly stated. Thank you for this article. I wish the project success and even though it’s small and temporary, every little helps.

And this deliberate erasure is happening, incrementally, right in front of us, day by day. It’s been happening since 1947. It’s the same ongoing process that has one final aim, one agenda and they won’t stop until it’s achieved. They will never stop. They need to be stopped

Alice Rothchild,

Thank you for speaking out and for all the good things you do.

You are s hero in the eyes of the Palestinian People. You are a very brave person… I can imagine the personal attacks on your character, the calumnies you have to withstand for the stand you so honourably take! ( same as Gideon Levy , Amira Haas , Ilan Pappe, Max Blumenthal, et al) !

You have our eternal gratitude !

I wish that a similar Nakba Museum would be created in London very soon .

Thanks for this. Israel has been relentless in erasing as much traces as it can of Palestine and its people, in its ruthless project of the denial of a real history and memory of Palestine for its people. As an addendum, i attended a screening of a film about cultural memory through cinema – the Palestinian film archive was kept in a building in Beirut, beside the PLO HQ I believe. The archive was the target of the first bomb when Israel attacked Lebanon in 1982. That tells its own story, although many Palestinians and Israelis believe that Mossad appropriated the archive for its own purposes and it still exists, probably never to be seen again.

This filmmaker has attempted a reconstruction of memories for which there are no existing images any more. It is a short, well worth looking at:

http://www.animateprojects.org/films/by_date/2009/for_cultural