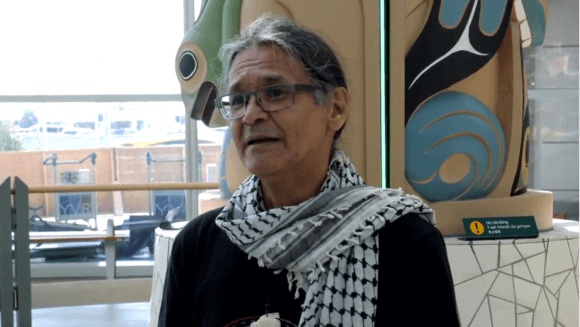

Larry Commodore is a long-time indigenous rights activist and former elected chief of the Soowahlie community of the Stó:lō Nation, near Vancouver. He was invited to participate in the Freedom Flotilla, and was a passenger on the al-Awda when masked, armed Israeli soldiers violently surrounded and boarded the vessel in international waters.

His foot and bladder were injured when the Israeli forces dragged him off the boat in Ashdod. In Givon prison in Ramle, he was verbally abused and denied treatment for his bladder for two days, despite the urgency of his condition. He finally got the catheter he needed. After four days of detention, Larry was deported and is now safely back in the Soowahlie community.

Larry Commodore and I were able to talk by telephone a few nights ago. His voice was full of a beautiful Northern First Nations lilt, emanating a gentleness and modesty of character that are still lingering in my spirit. With his permission, I have edited our conversation for length and clarity.

Kim Jensen: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me.

Larry Commodore: Thank you.

KJ: Can you tell me about where you come from?

LC: I live in the Soowahlie community. There are 24 communities in the Stó:lō Nation. We are called the People of the River, and we are also part of the Ts’elxwéyeqw tribe. The Soowahlie community is a small place. There are about 350 people living on the rez here.

KJ: What’s it like there? What is the economy?

LC: We live close to a resort here, the Cultus Lake resort community. It has waterslides and swimming and boating—all that kind of stuff. In terms of economy, we don’t have a lot going here. We’ve got a campsite and a gravel operation. That’s about our main source of revenue on the rez. We are kind of small in acreage. We only have 100 acres.

KJ: Oh, that’s really small.

LC: It’s because we are a non-treaty people. Our land was stolen from us. In 1864 they laid out the Soowahlie Indian reserve, and a promise was made—it was called the Crown’s Promise—that this reserve would be protected, but we would also get revenue from the rest of our traditional territory. But that promise didn’t come through. That was how we became impoverished. We are not a rich community at all. Far from it. Traditionally, before contact, we were considered one of the wealthiest of the original first nations because of the abundance of our natural resources.

KJ: So now you have a gravel mine and a campsite. Is that where people going to the resort stay?

LC: Yup. It gets pretty busy up here in the summer.

KJ: How do you feel about that?

LC: [Laughs] Well, I rarely go up to Cultus Lake. Like most of the locals, we just kind of put up with it.

KJ: How is what you have just described connected with the story of Palestine?

LC: Well, the whole basis of settler colonialism is to exploit the resources, to take the land from the natives. That’s the whole program—and that’s what’s happening in Palestine and here. Our resources are being exploited and we’re not benefitting from it. And the settler-colonialists are. BC, Canada is one of the wealthiest places in the world, and it’s because they stole it from us. And that’s what’s happening to Palestinians too. In Gaza I guess there’s some offshore oil or gas resources that Israel wants to exploit, so they’re getting rid of the people.

KJ: When did you first learn about this?

LC: About 30 years ago. I came across something that Yasser Arafat had said—that the Palestinians are the Red Indians of the Middle East and that kind of gave me pause, kind of resonated with me. So I started looking more into it. I read Chomsky, Norman Finkelstein, Edward Said, and other writers and of course, and started following the news. It really outraged me.

KJ: Was there a specific event that spurred you to want to be more actively involved?

LC: Two years ago, I went to a Palestinian solidarity conference at a university just down the road from me here and I met up with Rachel Corrie’s parents. I had known about Rachel Corrie from the time she was murdered in the early 2000’s. And I could really relate to her parents. I could really relate to their loss. A lot of indigenous community members have lost family members. I’ve lost family members too, so we know what loss is like. I could really identify with Cindy and Craig there.

KJ: They are such amazing people.

JC: And then of course there were Palestinians too, and we developed a rapport right away. And I met a Jewish friend of mine there, Sid Shniad from Independent Jewish Voices. But the person that had the most impact was Hanna Kawas. He’s with the Canadian Palestine Association—and has been in in exile here a few years and has worked with other native activists too. And I met with other Palestinian activists too and learned about their struggles. So when I was asked to go on the boat to break the blockade Gaza, of course I wanted to go.

KJ: You were aboard the al-Awda for the last leg of its journey from Palermo to Palestine. What memories of the trip will stay with you?

LC: Well, there were 22 of us and each of the others were extraordinary people in their own right. I was quite impressed with my shipmates. Most of our intimate time was standing on watch—we had two four-hour watches a day—so we really got to know each other. We really had a great time singing, telling jokes, being silly on the watch, making up songs.

KJ: Sounds fun! What kind of songs?

LC: [Laughs] Well Mikkel, the radio operator, he knew a few sea songs there. And the Norwegians had a strong sea background—more than the rest of us—they had some sea songs, but most of the time we were making up songs, and being silly, and not worrying about too much else. We were just a group of loving, caring people being together.

KJ: Well that’s lovely. I mean that’s what it is all about, right? The brotherhood and sisterhood we share.

LC: Exactly. I guess you can say we were modeling how societies should work.

KJ: Speaking of how societies should work, the Freedom Flotilla Coalition has committed itself to nonviolent resistance in its actions, and that leaves you very vulnerable out on the open sea. Were you afraid?

LC: I was more angry than afraid. I had prepared pretty well for how I would react if something happened directly to me, but what I hadn’t prepared enough for was my reaction when my shipmates were being assaulted.

KJ: What was that like? To see your shipmates being beaten and tasered?

LC: Well that’s what got me going. That is what got me really quite angry—when I watched one of our guys on the deck being put down by an Israeli commando. It pissed me off. It was hard to hold my tongue. When the Israelis were guarding us, I was so pissed off. I was asking them, “Why are you wearing masks, only criminals wear masks?” They were really quite brutal.

KJ: And you were assaulted too. When you arrived at port, they verbally assaulted you and dragged you off the boat. In prison, they stitched up your gashed foot, but denied you care for the bladder until the last day. After all of this, I’m wondering if are you planning to try to get compensation.

LC: We’re looking into that. That’s going to be our next step. I spoke with David Heap, and we’re putting together our case. Because everything that I had with me was stolen, except my passport. Everything was stolen. And the other participants, all of their money was stolen too. So at the last count, there was about $4,000 stolen.

KJ: Well they better give it back. It’s not their property.

LC: Exactly. I mean, what kind of professional army stoops to petty thievery?

KJ: Yes, it’s looting.

LC: Yup. It’s what pirates do. So that’s what we’re working on now, but there is still a good bit of evidence to be collected.

KJ: Are you facing criminal charges in Israel?

LC: No, I’m not. But they banned me for 10 years. I’m not allowed to Israel for 10 years [laughs]. Well, it’s kind of strange because I wasn’t planning to go to Israel. They’re the ones who dragged me into Israel. They dragged me in, then kicked me out again [Laughs].

KJ: How do these first-hand experiences reinforce the similarities between your people’s struggles and the Palestinians?

LC: It’s that settler colonial mindset. It’s all about exploiting our land and our resources, and using the thin veneer of “the rule of law” to acquire our resources. It’s more the rule BY law, rather than the rule OF law that is used to oppress us. I’ve always said that there’s no justice in the colonizer’s court. There in Palestine, and in Canada too.

KJ: The rule BY law, not the rule OF law.

LC: Another similarity is what’s happening to the fishermen in Gaza. They are being killed, not infrequently, and are prevented from pursuing their indigenous right to fish. We, the Stó:lō people, we are people of the river. Our main source of protein comes from the wild salmon. It’s been our main source of protein for thousands of years. They say our bones are made of it.

KJ: And what are the differences that you see?

LC: I guess the big difference right now is the level of violence. For us, there’s not that scale of violence, at least not right now. And that really concerns me, because we’re dealing with what they call inter-generational trauma. Our parents were brought into residential schools where they were abused—sexually, psychologically, mentally, and physically. And one of the doctors who has studied trauma is finding out about how this affects the DNA of generations of people. And so I wonder how the greater level of violence will impact the children of Palestine. Dr. Gabor Maté is the one who did that research.

KJ: This thought is making me so sad. To think of the violence that the children of Gaza are being subjected to.

LC: But there is a beautiful thing to remember. This is a worldwide grassroots effort. The Freedom Flotilla Coalition has given us a beautiful opportunity to engage with our own communities. Because of this trip, my community has been really worried about me, and now they are holding a dinner and a ceremony for me. This is an opportunity for me to engage with them, to explain some of what’s going on in Gaza.

So as a grassroots organizer, I’m quite grateful to the coalition for giving me this opportunity. Of course in the whole area up here, people are talking a lot, and it’s been in the media. It’s been quite an experience in the last few days. Literally hundreds of people have sent their regards, encouraging me, and telling me that I did a good thing.

KJ: I’m glad to hear that. So here comes that well-worn interview question. If you could talk to the Israeli people as a whole, what would you say?

LC: Well, I’m not so sure talking really does much. Here in Canada, we’ve been told that we’ve got to educate the non-natives. I’ve heard that for a couple of generations. I’m 63 now. So I get kind of cynical about this question. I don’t think we can convert people with talk. I think actions, like the one we just did, speak a lot more than just verbal communication.

KJ: I agree. So will you go on any more Freedom Flotilla actions in the future?

LC: [Laughs] Yup. With no hesitation at all.

RE: [W]e’re dealing with what they call inter-generational trauma. Our parents were brought into residential schools where they were abused—sexually, psychologically, mentally, and physically. And one of the doctors who has studied trauma is finding out about how this affects the DNA of generations of people. ~ Larry Commodore

LISTEN TO:

■ “Born Anxious: The Lifelong Impact of Early Life Adversity” w/ Daniel P Keating | Majority Report | September 18, 2017

Daniel P. Keating, a Professor of Education and the University of Michigan and author of, Born Anxious: The Lifelong Impact of Early Life Adversity – and How to Break the Cycle, explains how stress gets transmitted, what is epigenetic. The advantages and disadvantages of stress. Why America is becoming more stressed. Generational stress and group oppression. The individual and group implications of heightened stress levels and measuring stress levels, education and inequality. Why all groups are effected by enhanced stress and what are the policy solutions to the stress crisis?

● LINK TO AUDIO ➤ https://majority.fm/2017/09/18/918-born-anxious-the-lifelong-impact-of-early-life-adversity-w-daniel-p-keating/

● LINK TO VIDEO ➤ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XMGmaPlCMV8

P.S.

■ Epigenetics

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia ~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epigenetics

[EXCERPT] Epigenetics is the study of heritable phenotype changes that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence.[1] The Greek prefix epi- (ἐπι- “over, outside of, around”) in epigenetics implies features that are “on top of” or “in addition to” the traditional genetic basis for inheritance.[2] Epigenetics most often denotes changes that affect gene activity and expression, but can also be used to describe any heritable phenotypic change. Such effects on cellular and physiological phenotypic traits may result from external or environmental factors, or be part of normal developmental program. The standard definition of epigenetics requires these alterations to be heritable,[3][4] either in the progeny of cells or of organisms.

The term also refers to the changes themselves: functionally relevant changes to the genome that do not involve a change in the nucleotide sequence. Examples of mechanisms that produce such changes are DNA methylation and histone modification, each of which alters how genes are expressed without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Gene expression can be controlled through the action of repressor proteins that attach to silencer regions of the DNA. These epigenetic changes may last through cell divisions for the duration of the cell’s life, and may also last for multiple generations even though they do not involve changes in the underlying DNA sequence of the organism;[5] instead, non-genetic factors cause the organism’s genes to behave (or “express themselves”) differently.[6]

One example of an epigenetic change in eukaryotic biology is the process of cellular differentiation. During morphogenesis, totipotent stem cells become the various pluripotent cell lines of the embryo, which in turn become fully differentiated cells. In other words, as a single fertilized egg cell – the zygote – continues to divide, the resulting daughter cells change into all the different cell types in an organism, including neurons, muscle cells, epithelium, endothelium of blood vessels, etc., by activating some genes while inhibiting the expression of others.[7]

Historically, some phenomena not necessarily heritable have also been described as epigenetic. For example, the term epigenetic has been used to describe any modification of chromosomal regions, especially histone modifications, whether or not these changes are heritable or associated with a phenotype. The consensus definition now requires a trait to be heritable for it to be considered epigenetic.[4] . . .

Reading this makes me nostalgic, since I was on the 2010 Freedom Flotilla. As Larry implies, we experienced the highest of highs – living a dream of true brotherhood with people of all backgrounds from all around the world (there were about 45 different nationalities in our flotilla with every race and religion represented) – to the lowest of lows, being physically and psychologically abused in ways most of us had never experienced but which pale by comparison to what Palestinians have to endure daily.

Having said this, I have to implore all of us, yet again, to think long and hard about continuing the flotilla movement. We need to determine if there are better, more creative and valuable ways to spend precious time and resources in the service of the people of Palestine.

LARRY COMMODORE- “I don’t think we can convert people with talk.”

Surely not those who think of themselves as the eternal victims. And certainly not those whose privilege depends upon holding others down, hence, who demonize their victims in order to justify their privilege. The nobility/elite always despise the peasants whom they look down upon as a basket of deplorables. Zero empathy.

“Yup. It’s what pirates do. ”

So why be surprised that the Israelis do it?