Two days after the horrific murder of 11 Jews at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, I was sitting in my classroom where I teach, listening to several Jewish students grapple with understanding their suffering in response to the murders. They were scared, worried, confused. As a high school teacher in a large urban public school, I’ve become a resource for many Jewish students who long for a Jewish connection throughout the busy school day. Most of them are Zionists. I’m not out as an anti-Zionist at my school–it’s not safe for me to be–but I also wouldn’t say that I walk around pretending to be a Zionist. When I listen to my Zionist students trying to make sense of what is believed to be the deadliest attack on Jews in American history, I understand their suffering.

Even when they talk about their love for Israel, I can understand this, too, because I used to think like they do. My path to anti-Zionism is always through Zionism first–the new neural pathways in the brain aren’t as deep yet as the old ones I constantly fight against. And I think some of my students can continue to grow their capacity, too, and to have empathy for all those who suffer.

Later that day, when I was walking with some of these Jewish students, we saw a sign for an Israeli club meeting that afternoon in a colleague’s classroom. The sign said it would be a space to honor the victims. But this is also the club that provides pro-Israel propaganda to teens with outside support from private pro-Zionist organizations. I didn’t say anything to my students, of course–that I hoped the sponsors of this meeting wouldn’t use the anti-Semitic murders as a way to build teenagers’ love for Israel. I know these students needed a place to mourn and to process their discomfort, but it shouldn’t be at the expense of Palestinian suffering.

“At least we can always go to Israel if there’s more anti-Semitism,” was the first thing that came to my mind when I first learned about the murders. Strangely, this sentence was in my mother’s voice–though it was in my head–for she has said this to me over the years when antisemitic incidents have happened to Jews in the U.S.

It was unusual that this phrase materialized in my mind after the murders, but not much makes sense when people are suffering. It was also odd that the sentence arose in my mind, given that I no longer believe in Israel as a nation-state for the Jews. But I was an ardent Zionist for decades, and so my brain is still wired, it seems, to revert to old ways of thinking. Growing up, I shared my mother’s fears of anti-Semitism, for we had both experienced it first-hand at the school at which she taught and which I attended, as well as in our neighborhood, so I had learned at an early age to be wary of how people could treat the Jews. “At least we can always go to Israel if there’s more anti-Semitism,” she’d say, and I believed–because my mother believed–that Israel would save us from anti-Semitism.

It’s peculiar, really, all these labels. I’m an anti-Zionist who is perceived as a Zionist by people who need to see me this way, namely my coworkers and students. If I reveal who I really am, I risk being labeled an antisemite, which is the very thing I’m afraid of: more anti-Semitism.

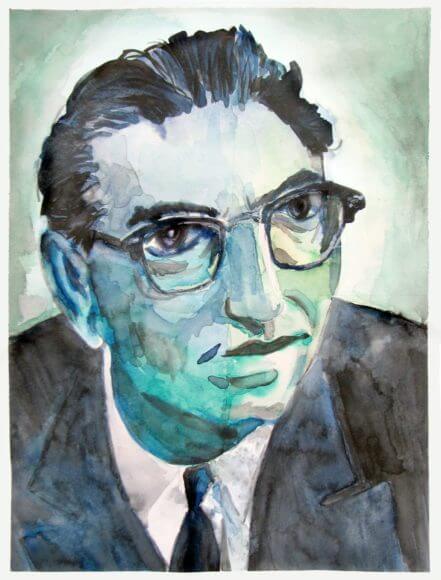

During the last few days, I’ve been rereading sections of Viktor Frankl’s 1959 book, Man’s Search for Meaning, which he wrote after surviving four camps, including Auschwitz. I return to this book often when I’m suffering. It felt somehow appropriate to read it again this week.

In his chapter on the psychology of the liberated prisoner, Frankl writes of one man in particular who made it out of the camps. This man thought that since he had survived the horror of the camps and had come back to his home town in Vienna, his time of extreme suffering would be over. Upon returning, however, he experienced a bitterness when people told him that they didn’t know what was happening in the camps, and that, they, too, had suffered. As a result, he also experienced extreme disillusionment; returning to his hometown might not actually mean the end of his suffering:

A man who for years had thought he had reached the absolute limit of all possible suffering now found that suffering has no limits, and that he could suffer still more, and still more intensely.

Some other men made it back to their hometown only to find that no one awaited them. The person they had dreamed of seeing at home was not there, and would never be there. “Woe to him who, when the day of his dreams finally came,” Frankl writes, “found it so different from all that he had longed for.” The people realized that there simply was no end to their suffering. The only thing left for anyone to do when this happens, Frankl writes, is to try to find meaning from one’s suffering.

I’m trying to do this, too, to find meaning while mourning the loss of life; as I write this, there has been yet another shooting in the U.S. There have now been 307 mass shootings in the U.S. in 2018. Anti-Semitism is on the rise, and I’m scared to be labeled an anti-Semite for being an anti-Zionist–and disturbed by the idea that we live in a world where I could represent to others something I’m afraid of!

But ultimately, these labels are meaningless, too. I wasn’t in the Tree of Life synagogue. I didn’t know any of those who were killed. All I know is they died before reaching their full potential as sentient beings roaming this earth–as countless others have before them, and have since.

And so many of us are left suffering for so many reasons, really, wondering, dreaming, that if only things were different, better, we might come to know what Frankl says towards the end of his book: “How beautiful the world could be!”

RE: “If I reveal who I really am, I risk being labeled an antisemite, which is the very thing I’m afraid of: more anti-Semitism.” ~ Liz Rose

MY COMMENT: Touché!

“It’s peculiar, really, all these labels. I’m an anti-Zionist who is perceived as a Zionist by people who need to see me this way, namely my coworkers and students. If I reveal who I really am, I risk being labeled an antisemite, which is the very thing I’m afraid of: more anti-Semitism.”

And don’t forget, if you do say you are anti-Zionist, remember to have sure-fire solutions for all post-exile Jewish problems at hand.

“How beautiful the world could be!”

“What do sad people have in common? It seems they have built a shrine to the past and often go there and do a strange wail and worship. What is the beginning of happiness? It is to stop being so religious like that”

Hafez

(The Khwaja from Shiraz)