The following is a speech given on the panel “Exploring Liberation Theology in the Palestinian Struggle” during the International Conference on Palestine held at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs, İstanbul Sabahattin Zaim Üniversitesi, Istanbul Turkey, April 27-29.

This post is part of Marc H. Ellis’s “Exile and the Prophetic” feature for Mondoweiss. To read the entire series visit the archive page.

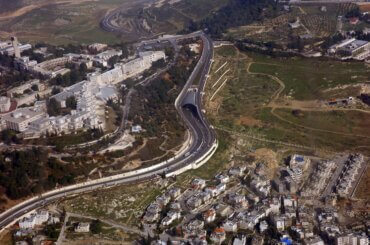

Two years ago in Jerusalem, I celebrated the 30th anniversary of my book, Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation. Though I use the word, “celebrated,” noting that my book is still relevant in our fast moving times, the very relevance of my book occasioned a mourning. In the decades since its publication regression in Israel-Palestine rather than progress has been the watchword. What has unfolded during these decades is decisive. It has rendered the occupation of Palestine permanent. It has brought us to the end of ethical Jewish history – from which there will be no return.

When I launched my Jewish Theology of Liberation I was unknown in Israel and elsewhere. I remember wondering why the audience was overflowing. The atmosphere was tense. Something was in the air. In Jerusalem, I called for a (real) two state solution, with East Jerusalem as the capital of Palestine. I called for the Prime Minister of Israel to confess to the Palestinian people the following: “What we, as Jews, have done to you, the Palestinian people, is wrong. What we, as Jews, are doing to you, the Palestinian people, is wrong. We pledge to you a new beginning. Let us take the road of justice and equality into the future.” I called for Israel, with the help of Jews around the world, to pay reparations to the Palestinian people. To put it mildly, my words were controversial.

Months after my book launch the Palestinian Uprising began. In 1989, a second edition was issued with a new Epilogue: “The Palestinian Uprising and the Future of the Jewish People.” During this time I wrote a sequel, published in 1990, with a three part title that still resonates: Beyond Innocence and Redemption: Confronting the Holocaust and Israeli Power: Creating a Moral Future for the Jewish People. With the Great March of Return and the recent Israeli elections, the thoughts contained in both books remain ingrained in Jewish history, albeit with a terrible twist: Within a permanent occupation, at the end of ethical Jewish history, what is the future for Jews and Palestinians?

My Jewish Theology of Liberation begins with the Exodus narrative. In the Biblical account, Jewish nationality, culture and religiosity are forged in an act of liberation enacted by a liberating God. For me, though, the Exodus points to a more important fact about Jewish history: that the prophetic, which reappears in the Land, is our Jewish indigenous. The critique of unjust power, especially within our own community, is the litmus test for the affirmation of God. Put simply: In Jewish life, No justice, No God.

With the creation of the state of Israel the equation of justice and God was already under assault. This is why that, after mentioning the Exodus, I shifted to the contemporary formative event of Jewish history, the Holocaust. Where was God and the prophetic at Auschwitz?

The state of Israel is a response to the twists and turns of European Christian history, culminating in the Holocaust. Yet in Israel’s birth a terrible evil was committed, the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. In Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation, I affirm Jewish empowerment after the Holocaust but question the cost of Israel’s empowerment. At the same time, I point to an ethical path to redress the wrong done in the creation of Israel.

The first Palestinian Uprising represented the possibility for a reckoning and forward movement. In the decades since, Israel, with the assistance of the Jewish establishment in America and, surprisingly with the help of progressive Jews as well, foreclosed that possibility. Over the years both groups insured there would be no way forward.

A Jewish Theology of Liberation questioned what was occurring in the Jewish community in the United States. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Jewish community was among the most liberal communities in America – on civil and women’s rights and on economic, political and international affairs. As the 1980s arrived, Jewish liberalism tacked right; neo-conservatism became the hallmark of Jewish thought and commitment. I wondered about this drift and the reasons for it. Part of my Jewish Theology of Liberation centered on the question: Is the neoconservative drift of the American Jewish community occasioned and furthered by the increasing centrality of the Holocaust and Israel to Jewish identity?

Many of these understandings of Israel and the world come within a consciousness that endures today and is formative. Though highly political in its outward manifestations, it takes on an ultimate concern, one might say a theological one. In a Jewish Theology of Liberation, I identify this consciousness as Holocaust Theology.

Holocaust Theology begins in the 1960s and solidifies after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. Whether justified or not, large parts of the Jewish world felt in the weeks before the 1967 war that the very existence of Israel was on the line. Many Jews feared that if Israel was defeated, Jews in Israel would be annihilated; a second Holocaust would occur. Thus Israel’s swift victory in the war seemed to some more than a military victory. Those, like Elie Wiesel, who experienced the Holocaust and feared another one, rejoiced. For Wiesel, victory in the 1967 war was a miracle in the making, especially after he with other Jews felt that the world, indeed God, had abandoned Jews during the Holocaust. Could Israel’s victory in the 1967 war be a redemptive response to the Holocaust?

Emil Fackenheim, himself briefly imprisoned during the war years, posited a new commandment in relation to the 1967 war, a commandment which he believed issued from the “Commanding Voice of Auschwitz” rather than the “Commanding Voice of Sinai” – “Thou Salt Not Grant Hitler Posthumous Victories.” Elie Wiesel saw Israel’s victory as fueled less by its military might than by the victims of the Holocaust who, in his mind, pressed Israel’s forces to victory.

Holocaust Theology became the introduction to my Jewish Theology of Liberation for a variety of political and religious reasons, though mostly because it presaged a deep identity shift within the Jewish people as a whole. Though controversial then and now, Holocaust Theology speaks to a people brutally assaulted, humiliated, maimed and murdered in Europe during the Nazi years. It speaks to the survival of an ancient people and tradition.

At least initially, Holocaust Theology also carried warnings about the misuse of the power Jews needed and had acquired, though mostly in the abstract and under a maximum definition of self-defense. Holocaust Theology does not acknowledge what Jews initially did on the Palestinian people in the creation of Israel. Nor does it address the injustice Israel continues to commit against the Palestinian people under a variety of forms of occupation.

For the most part, Holocaust Theology renders the Israeli occupation of Palestine and Palestinians themselves invisible. Israel is a Jewish drama of innocence and redemption. When visible, Holocaust theologians define Palestinians as challenging the need for Jewish empowerment and, worse, actively opposing it. Holocaust theologians do not understand the reasons Palestinians oppose Jewish power except to declare that Palestinians have a deep animus toward Jews and Jewish history. Within Holocaust Theology, Jews who argue with Israel’s empowerment, or parts thereof, are painted with a similar brush. In Holocaust Theology, Palestinians are mostly seen as anti-Semites. Jews who argue with Israel’s use of power against Palestinians are defined as self-hating.

The Interfaith Ecumenical Deal that emerges from the dialogue between Jews and Christians after the Holocaust was important in the early days of a Jewish Theology of Liberation. After the Holocaust, Jews instructed Christians to clean up their anti-Jewish theology. Many Christians wanted to do just that. Part of the dialogue, insisted by Jews, was that Christians accept Jewish self-definition. This includes Israel as central to Jewish life. And more, Jews in the dialogue insist Christians accept the centrality of Israel to Jews as the main vehicle of repentance for their sin of anti-Semitism. To further this understanding and imbue it with theological significance, Christians developed a Christian Holocaust Theology. In Christian Holocaust Theology, Christians and the Christian covenant are dependent on their Jewish forerunners and Jewish empowerment, especially in Israel.

Since Jewish Holocaust Theology sees Jews as innocent in suffering and empowerment, including in the creation and maintenance of the state of Israel, any criticism of Israel vis-a-vis Israel’s treatment of Palestinians is deemed a return to anti-Semitism. Quite soon after the 1967 war, the Jewish-Christian dialogue morphed into the Interfaith Ecumenical Deal. In this deal, Christian repentance for the sins of anti-Semitism is assured by Christian silence on the plight of Palestinians.

As with Jewish Holocaust Theology, Christian Holocaust Theology and the Interfaith Ecumenical Deal has a deep and abiding political impact in Europe, the site of the Holocaust, and in the United States, where an increasingly empowered Jewish community demands Israel be most favorably set apart in American foreign policy. Combined with the rise of Evangelical Christianity in America and in different parts of the world over the last decades, the concerted effort to suppress the indigenous Jewish prophetic becomes obvious. Jewish Holocaust Theology is explicit on this point with a logic spelled out in the following way: “The Jewish prophetic turned inward threatens the empowerment of Jews, especially in Israel; Taken to its final demand for justice for the aggrieved, in this case Palestinian freedom, the Jewish prophetic threatens the very existence of Israel; In so doing, the Jewish prophetic, intentionally or not, lays the groundwork for a second Holocaust.”

Yet in its inception, and against the odds, a Jewish Theology of Liberation recognized and was part of the revival of the Jewish prophetic precisely on the point Jewish Holocaust Theology feared most: Israel’s unjust power wielded against the Palestinian people. Though Israel’s invasion of Lebanon and the crushing of the Palestinian Uprising in the 1980s mark the beginnings of this fracture in Jewish consciousness, it was during and after the second uprising in 2000 and beyond that a final prophetic break occurred.

The initial division between what I have called Constantinian Jews or, if you prefer, Empire Jews, and Progressive Jews, occurred within the second Palestinian Uprising. Progressive Jews criticized the Jewish establishment with regard to Palestinians. Yet the criticism was often paternalistic toward Palestinians and critical of Jews who see the crisis in Israel-Palestine more critically. The second Palestinian Uprising confirmed that Progressive Jews essentially functioned as the Left-wing of Constantinian Judaism.

A third group of Jews, Jews of Conscience, realized that the Israeli occupation of Palestine is permanently imbedded in Israeli and Jewish life. Jews of Conscience understand that the Constantinian-Progressive Jewish axis is complicit in an injustice that will continue. Only by refusing this axis can Jews and Palestinians be saved from a future characterized by a permanent occupation and, by definition, the end of ethical Jewish history.

If we fast forward to the present, the continuing relevance of a Jewish Theology of Liberation becomes clear. In writings since 1987, I have narrated the failure of Israel and the Jewish establishments in America and elsewhere. As well, I have narrated the explosion of Jewish prophetic movements over the last decades. Attempts at detailing and expanding a Jewish Theology of Liberation are ongoing and include critical historical analysis of Israel’s founding, the importance of international law, the expanding BDS movement and questions about the coloniality of Israel and Jewish life. Though all have their importance, they make sense only in the broader framework that a Jewish Theology of Liberation provides. The central question I raised more than thirty years ago remains: Has Jewish empowerment in Israel and elsewhere empowered Jews? Or has the abuse of that empowerment enslaved Jews in and outside of Israel?

I speak as Passover comes to an end. But this year, as a Jewish Theology of Liberation enters its fourth decade, with an occupation that has, in my view, become permanent, I suggested that Passover be, literally, passed over. In essence, out of conscience, and in light of the situation in Israel-Palestine, especially but not limited to the maiming and murdering of Gazans participating in the Great March of Return, I argued that all attempts at reforming Jewish life, including in the political and religious arenas, should be suspended. Hence my #NoPassover signage in my writing running up to Passover this year.

Just days before Passover and a week or so before I boarded the plane for Istanbul, I read of three young Gazans who attempted to cross back across the border into what is now Israel. All three were shot by Israeli soldiers, then held in Israel. Ten days later the lifeless body of the 16-year-old, Ishaq Abd al-Mu’ti Eshtawi, from Rafah City, was returned. When I saw the story I wrote in my diary: “The Israeli soldiers carry the wounded Gazan away. His crime? Trying to return home. So they shot him and took him in. Now he’s returned. To his other home. Dead. I ask: When is silence better than empty words of outrage and deliverance? At least change the subject. Out of respect for the dead and the living. Who tomorrow might be murdered. #NoPassover.”

Sometimes I am asked where would I begin if I were to write a Jewish Theology of Liberation today from scratch. I could not begin with the Exodus, since Jewish liberation cannot be a one-sided affair and, besides, we are now aware of the complications of the Exodus narrative from a variety of perspectives, including Israel’s Biblical entry into the land and the consequences for the native inhabitants. I could not begin with the Holocaust either, since the Holocaust today functions as a blunt instrument against the aspirations of the Palestinian people and, as well, a blunt instrument against Jews of Conscience who embrace the prophetic.

Israel, of course, has failed to bring the redemption from the Holocaust it initially promised. Just the opposite has occurred. Today, Jews in Israel and beyond are enslaved to an empowerment characterized by ethnic cleansing, occupation and land theft. As the Jewish philosopher, Hannah Arendt, predicted in the 1940s, the formation of Israel has led to the militarization of Jewish life within and outside the state of Israel. The post-Holocaust Jewish hope for a demilitarization of the global community has given way to Israel’s free use of violence which, in turn, only encourages threats of violence against it.

A Jewish Theology of Liberation might begin with an addition to Emil Fackenheim’s 614th commandment or, more to the point, the positing of another commandment. While the 614th commandment represents the resolve for Jewish continuity after the Holocaust, crystallized in an empowered Israel – “Thou Shalt Not Hand Hitler Posthumous Victories” – the 615th Commandment places the desire for Jewish continuity and need for Jewish empowerment in a second after: after the Holocaust and after Israel – and what Israel has done and is doing to the Palestinian people. The 615th Commandment? “Thou Shalt Not Murder Those Who Resist Your Oppression.”

Fackenheim believed, what with the silence of God during the Holocaust and thus of Sinai, the 614th commandment was issued by the Commanding Voice of Auschwitz. The 615th commandment combines the Commanding Voice of Auschwitz with the Commanding Voice of Palestine. It is only by hearing and heeding these two voices that Israel, indeed Jews around the world, can move into an ethical future characterized by justice and equality.

‘Thou shalt not murder those who resist your oppression’.

Should it not be ‘thy oppression?’

Good to see conscience is alive and well in some hidden corners. While Ellis admonishes the world’s Jews, he offers no operating procedure to Palestinians. Should they hunker down and take the ravages? Or rise in Intifadas? Or keep up with those Great Marches of Return? Or start a war of independence?

klm – The author pretends that he is busy with universal ideas, but in reality he is busy only with the Jews. Now, it’s fine to be busy with just the Jews (if that’s your thing); however, here lies the answer to your puzzlement as to why there is no “operating procedure to Palestinians”. They’re not his issue at all.

i read a funny article on the pretentiousness of the many jews that have re-written their own version of the haggadah to conform to their personal views. I didn’t realize what a cliche it has become in so-called progressive circles. I remember the haggadahs in the 70s that included prayers for soviet jews. I thought it redundant but somewhat understandable in the context of zionism. but now the reinvention of the haggadah is off-the-wall hand-wringing stupidity but, have at it, it isn’t a crime. re-write the torah while your at it since nobody can prove who wrote it in the first place.