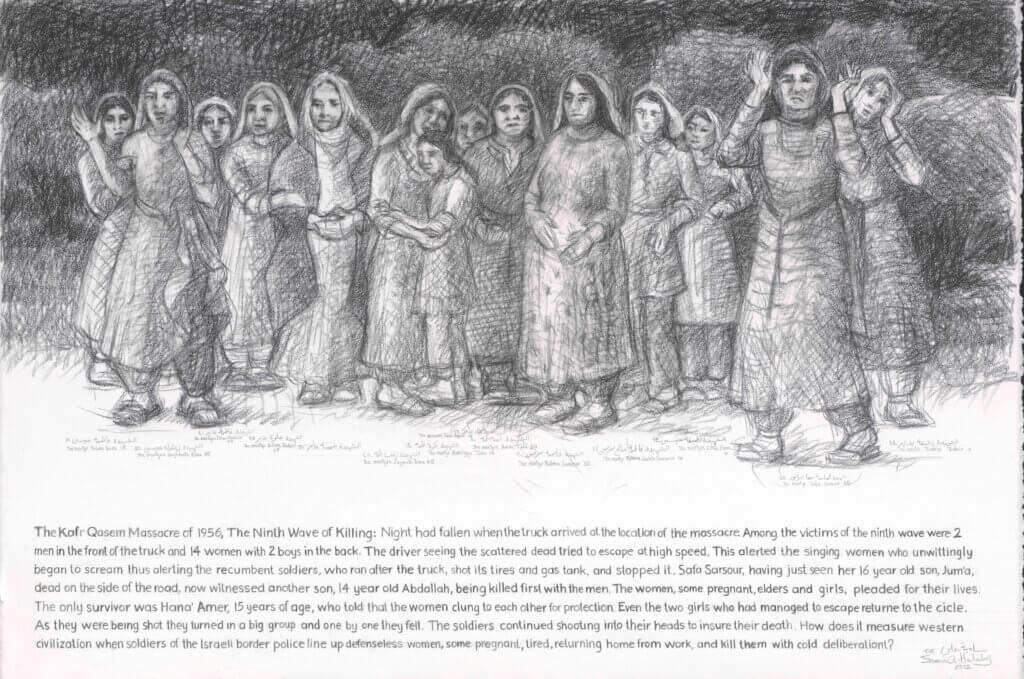

In Drawing the Kafr Qassem Massacre, Samia Halaby, the renowned Palestinian abstract expressionist, switched to draftsmanship. In heavily shaded lines in crayon on paper, Halaby evoked the 49 victims of the 1956 massacre, documenting those who were shot when the Israel Border Police opened fire on Palestinian workers returning home at the end of the day. Each wave of killing is illustrated location after location. Witness statements document not only the facts of what happened but also the dissemination of information afterwards to the public and to the media.

Some sketches, like Fourteen Women of the Ninth Wave, 1999, have shades of Guernica about them: a long low horizontality of assembled, anguished women, broken up by the angle of a woman’s face upturned towards the sky. In other sketches Halaby’s abstract style seems to seep through, where masses of limbs in a crowd evokes the diagonal vectors that her work is typically organized along. But the drawings, in the main, do the sober work of documenting those that were lost, in a restrained, almost classical style.

Drawing the Kafr Qassem Massacre is a book, that is, political in origin and in design, a flexing of communicative and emotional intent parallel to an otherwise abstracted practice. Within Halaby’s decades-long career, it raises the question of how the Palestinian activist addresses and locates politics in her work – and whether her Marxist understanding of politics is fast receding from an art world that is increasingly focused on questions of political efficacy.

“Where are we now?” she asks when I spoke to her in her TriBeCa studio via Zoom in May. “Climate change is circling the globe. We have two superpowers representing two powerful classes. We have an economy that is going south and things are very scary right now for a lot of people, and a lot of young people. This divide is in every country. I think of the theorist of the Workers World Party in, Sam Marcy, and one phrase from him keeps reoccurring to me: global class war. We are in a situation of global class war.”

Halaby was born in 1936 in Jerusalem and was exiled from Palestine during the Nakba in 1948, first moving to Lebanon and then to the Midwestern United States with her family. She received a BA from the University of Cincinnati and then an MFA from Indiana University, and taught painting in the US, including ten years at Yale School of Art, where she was the first female assistant professor. She is active in political protests against the Israeli occupation, has produced anti-war posters and banners, in addition to the astounding Drawing the Kafr Qassem Massacre, and speaks publicly about her politics.

Her commitment has not come without its costs, as the Emirati thinker Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, whose Barjeel Art Foundation has supported her work, explains.

“As a child who was forced into being displaced, Samia Halaby carried wounds of her experience with her throughout her life, translating into her activism and her art,” he says. “She has constantly championed the causes that she believes in, which has cost her opportunities in life, a decision that she has taken with full consciousness. Samia’s message is consistent towards whoever she speaks to, whether it is a smaller group of individuals or a public talk at the Guggenheim in New York.”

Halaby’s activism also raises the question of where – and how – politics is located in an artist’s work. In addition to more clearly polemical work such as Drawing the Kafr Qassem Massacre, the art she is best known for is abstract and beautiful: pink, green, and blue diagonals of color patterns, repeated across the canvas. Investigations of the illusion of volume, as metallic-looking cylinders criss-cross the picture plane. Where, you might ask, is the politics in this?

For Halaby, the answer is simple: in Marxist theory, art is a symptom of society, giving insight into society’s progression through political and economic stages. The thinking cuts like a knife through issue-driven politics.

“You know, I can make a banner and a poster,” she says. “Does that change what Rockefeller is going to decide to do with this money next year? No. Does that stop him from giving $4 billion to Israel? No matter how hard I try, or how often I walk the streets and demonstrate. But art is a flowering of society. It’s not the other way around.”

“The Impressionists are really amazing,” she continues. “Take note that they are popular and beloved by everybody. Which is not artificial – people really admire them, not because they’re sweet and fruity, but because they recognize in them the first step away from praising the ruling class, to praising the middle class and even the worker. By the time you get to some of the French Cubists, like [Fernand] Léger and the early Constructivists, you see clear praise of the worker and a growing focus on the general and on abstraction. To me, abstraction is an efflorescence of working class revolution.”

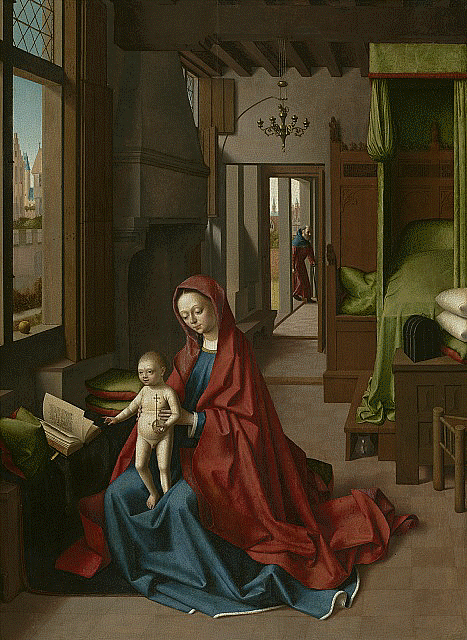

Her own artwork participates in this shift towards political emancipation. It was born of an encounter with a Dutch still life from the fifteenth century, a conventional but affecting image of motherhood that she saw at the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, in a moment when she was “lost” artistically, she says. The central point of the image, Virgin and Child in a Domestic Interior (1460–67, by Petrus Christus), is the dyad of the Madonna and Christ child, both illuminated by the light from the sunny window. But Halaby focused on one, almost extraneous detail: an apple sitting on the windowsill, neither brilliantly colored nor obviously connected to the rest of the scene.

“In the north, having fresh fruit must have meant something very special – it might have symbolized fertility,” she says. “I went home and decided that I was going to paint an exploration of the apple, by painting a sphere in some boxes, like the windowsill and the apple. And I did and it became a new way of painting for me.”

Back in the studio, she produced two astounding paintings of metallic spheres, depicting a large steel ball bearing that she happened to have in her studio. In the reflection of one of them, you can make out Halaby herself, distorted in the sphere, as if in reference to Hans Holbein’s anamorphic object in the Ambassadors.

She then took the shapes and abstracted them, moving away from what they represented and towards the shapes itself: a sphere, a rectangle, the impression of bulbousness. She began, in her words, “conjugating” them, shifting away from Renaissance perspective, testing how cylinders could be twisted and appear as helixes or arranged in circles giving way to swirls. Working with a varied palette of bright colors, she began looking at the overtones in metals, drawing out the colors one sees but doesn’t name – the yellows in gold or the silvers in steel.

Next, she laid them in patterns across the canvas, in an acknowledgment of what she calls the failures in Renaissance perspective: the fact that the whole project of perspective, with one single vantage point upon which vectors of vision shoot out, only works if the person stands still. (Or for that matter, sees the world with one eye shut.) What happens, she asks, if someone moves?

The subsequent works she produced, throughout the 1970s, combine illusion and abstraction, as if exploring whether illusion can still be possible – or should be possible – if one moves away from Renaissance perspective. Movement is key to the works: they look like they are arrested mid-flight, as if a pink was about to morph into purple, a spiral were to keep going, or a cylinder were going to revolve to show you its back side. Given the propensity towards depicting movement it seems only natural that she moved towards actual kinetic paintings. In the 1980s she taught herself to code, having bought an Amiga 1000 computer in a foreclosure sale in New York’s financial district. She made digital prints and animations, often performed live and set to music. Yafa celebrates the oranges from the town where she lived before leaving Palestine; Brass Women (both 1992) was born of her political activism, being inspired by the Black and Latino women that she had encountered at political demonstrations, as she told an Online Cultural Majlis talk in 2020.

“I attended this small conference on computers in Philadelphia,” she recalls. “It was more focused on electronic music than imagery. Late at night, when the conference would be over for the day, the musicians would get on stage, as all their equipment was already there. And they would jam, freely. I sat watching them, the only one in the audience, and was thinking, I’d love to be up there doing an image to accompany the sound. And so for a year and a half I worked on my program, and that became the second stage of my work.”

Halaby moved away from programming in the 1990s, dismayed at the relatively low interest in digital art, and returned to making acrylics on canvas. The works of this later period resumed the widening towards external stimuli that began in the 1980s, when she began to fold in the outside world. In the Dome of the Rock series, from 1980 to 1982, she incorporated the variegated texture of the marble inlay in the Jerusalem mosque into a series of oils. The paintings moved away from the shiny, metallic flavor of her earlier geometric abstractions; the colors on the canvas are flecked, imperfect, organic; they sit more loosely amongst one another. Her painting style has since become even unpinned, again incorporating the natural world – the pinks and purples of flowers, the greens of leaves, drawn both from the world around her and her memories of Palestine.

Around that time she also began writing a history of Palestinian artists, traveling throughout Palestine, Syria and Lebanon to interview 46 artists for what became the 2002 survey Liberation Art of Palestine. The tome shows Halaby’s intellectual approach to art, but it is also interestingly one of a number of art histories written by Palestinian artists. Kamel Boullata published Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present in 2009; Ala Younis published a monograph on Abdul Hay Mosallam Zarara in 2020. The motivation is partly to do, Halaby says, with the fact that few art historians were paying attention to Palestinian art at the time. And the situation on the ground was worse than neglect: Israeli agents were actively destroying the contents of studios, exhibitions, and archives.

But she also relates it to the revolutionary atmosphere in Palestine and Lebanon – which, she underlines, was not just a factor of Palestinians vs. Israelis, but again a revolutionary class consciousness that united Lebanese and Palestinian activists, based on economics, and which incited them to take the means of intellectual production into their own hands.

How much of this revolutionary mindset remains today – and how much should it? Halaby’s work is gaining increasing recognition: she is participating in the 2022 Singapore Biennial with one of her kinetic paintings, and has a large-scale retrospective forthcoming at a Gulf museum. Her work, especially from the 1970s to the 90s, is beautiful, vibrant, like music stilled. But some would say her beliefs also feel dated: part of the 20th century’s systemic theories that could explain away every problem. And her understanding that art is separate from the museums, magazines, and market feels at odds with a post-institutional critique generation that understands the art context as the art itself.

When I mention this, Zooming with her in her studio lined with five decades of production, she is undeterred.

“I am the artist and visual thinker – not the museums, magazines, and various institutions and administrations,” she replies. “They are incapable of seeing and recognizing the art of their time, and that is proven over and over and yet over again in their various histories. Their record of recognizing the art of their time is abysmal. Why would someone who loves painting and pictures want to work according to their morays?”

Melissa Gronlund

Melissa Gronlund is a writer based in London. She was previously the art correspondent for The National in Abu Dhabi, and her writings on contemporary art have appeared in The Times, The Guardian, The New Yorker, Artforum, Art Agenda, and Afterall journal, among other places. Originally from New York City, she studied Comparative Literature at Princeton University and Film Aesthetics at Oxford University.

1 of 2

Re: Kafr Qasem Massacre:

On October 29/56 at 4:30 P.M. (just over one hour after Israel began its invasion of Egypt), a unit of Israeli Border Police (or Frontier Police) led by Major Shmuel Melinki announced that a curfew would be imposed on Arab villages in the “Little Triangle” (near the armistice line with Jordan) from 5:00 P.M. until 6 A.M. the next morning. (Hirst, p. 185) The order for the curfew (which was to come in effect one hour earlier than previous ones) was given by Israel Defence Force battalion commander, Brigadier Yshishkar Shadmi, after being approved by the Commander of the Central Area, Major General Zvi Tsur, who had emphasized to his officers that ‘the safeguarding of the operation in the South [the Suez campaign] required that the area coterminous with Jordan be kept absolutely quiet.’ (Nakleh)

One of the villages put under curfew was Kafr Qasem which had a population of about 2000. The mukhtar (headman) protested to the Israeli Border Police that many of the villagers did not know about the curfew as they were working in the fields or elsewhere when it was declared.

Ignoring the mukhtar’s appeal, the Border Police set up road blocks & waited. “After 5 P.M. they stopped all villagers returning to Kfar Kassem, lined them up along the road & shot them. Men, women & children were cut down.” (Neff)

2 of 2

Of 16 olive pickers returning in one truck, only a sixteen-year-old girl survived; all but two of them were women, one of them 8 months pregnant. When it was over, by 6 P.M. [just one hour after the curfew came into effect], 47men, women & children had been slaughtered.” (Neff)

On 19 December 1956, the Israeli daily, Kol Haam provided a gruesome account of the slaughter at Kafr Qasem and how the bodies were disposed of: “[During the final stage of the massacre], the soldiers moved around finishing off whoever still had a pulse beating in him. Later on, the examination of these bodies showed that the soldiers had mutilated them, smashing the heads and cutting open the abdomens of some of the wounded women to finish them off. The only survivors were those who for some time lay buried under the corpses of their comrades. The soldiers looted whatever they could find, while going round the bodies doing their finishing-off job. On 31 October, a curfew was imposed on the village of Kafr Kassem, & during that time, the Israeli police brought over some of the villagers from neighboring Galgoulia & ordered them to bury the corpses, which included fathers, mothers, sons & daughters.” (Kol Haam) 19 December 1956, quoted by Issa Nakleh)

The Israeli government attempted to cover up the Kafr Qasem massacre, but the public soon learned of it, thanks to certain Jews who hoped news of the massacre would frighten more Arabs into fleeing to Jordan. Brigadier Major Yshishkar Shadmi told Major Melinki ‘that the curfew must be extremely strict & that strong measures must be taken to enforce it. It would not be enough to arrest those who broke it – they must be shot.’