RETURNING

Palestinian Family Memories in Clay Reliefs, Photographs and Text

by Vera Tamari

152 pp. Educational Bookshop/Arab Image Foundation, £35.00

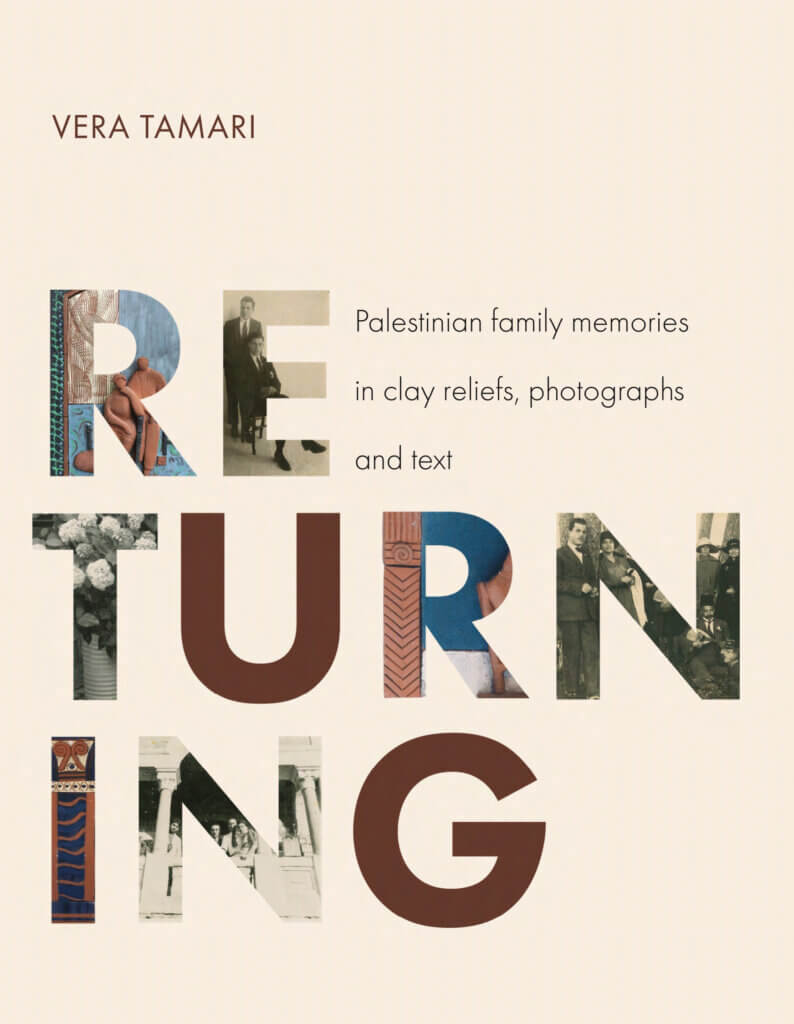

I experienced RETURNING: Palestinian Family Memories in Clay Reliefs, Photographs and Text, by Palestinian artist, Vera Tamari, as opening a triptych on the theme of returning — one panel exploring returning through the camera lens, a second through clay reliefs, and the third through texts. Tamari’s RETURNING is a tour de force, a deeply personal story of her family in Jaffa and Jerusalem before the Nakba, when approximately 750,000 Palestinians were exiled from their homes and the State of Israel was created. Tamari’s book documents the life of a typical Palestinian urban, middle-class family under the British Mandate, capturing its rich and sophisticated cultural life from the early 20th century until 1948. The cover itself heralds what is within the pages of the book, with its title appearing in embossed letters, each containing an image from the book.

Drawing on her father’s vast photo collection from Jaffa and Jerusalem in pre-Nakba Palestine, Tamari has sculpted, between 1989 and the mid 1990s, a series of terracotta bas-relief panels, which she entitled “Family Portraits.” More recently, she completed her project by paralleling the photographic images and her clay reliefs into personal written narratives: stories of love, loss, longing, and return.

Tamari delicately engages the readers with her text and the accompanying visual images, bringing to life historic Palestine in an attempt to scour the lost memory of our homeland, a loss that has been key to the work of many contemporary Palestinian artists.

Each one of Tamari’s chapter headings, photographs, and clay reliefs revisits aspects of Palestinian life, and are proof of a flourishing Palestinian society that existed long before the establishment of the State of Israel.

In “Woman at the Door,” Tamari’s mother, a modern woman who defied conventions, her hands behind her back, stands at the door of her house in Jaffa with flower pots at her sides. In “Unfulfilled Dreams,” a poignant chapter about Tamari’s aunts Olga and Alexandra Tamari, we see Olga sitting on a low stool next to a giant pot of hydrangeas, her sister Alexandra behind her, a hand on her shoulder. In “Picnic in Hebron,” the composition and balance, as noted by Tamari, are especially exquisite — a row of friends standing amid a row of tree trunks.

Through the media of art, photography, and texts, Tamari brings us into the fold of family and friends, who sat on a balcony, traveled to Hebron, posed for a studio photograph, or gathered for a masquerade ball. In RETURNING, Tamari chose to showcase with her photographs a life that has been lost, but that needs to be retraced, a life which was to be obliterated, but which continues to endure through the eyes and hands of artists, musicians, and writers, who persevere in honoring and celebrating Palestinian society pre-1948.

Tamari looks at photos with the meticulousness of an anthropologist digging into the relics of a past civilization. She slows us down, takes us gently by the hand, almost as though through a portal to another land, and with reverence, we enter together into the frame of a photograph to commune with its subjects. She notices every minute detail — her grandfather Nicola’s mustache and gloves in hand, her grandmother Adele’s bracelets adorning her arms, her father’s hairstyle and head attire, the exact number of calla lilies — ten, to be exact — in her mother’s bridal bouquet. Nothing goes unnoticed; everything comes to life. We are inside the photographs, in the photographer’s studio, on the balcony, at the wedding. We are not spectators, but active participants.

The clay reliefs are graceful representations of the photographs, crafted lovingly, almost as though the author’s hands caressed every face and brought it to life in clay form. Keeping the protagonists in the natural clay color while the backgrounds and frames are colored softly to give an ambiance and character to the place and time, Tamari’s terracotta frames are adorned with gray and white leaves, geometric designs, or classical columns in hues of blue, green, white, and terracotta orange. There is something soft and tender about the way she sculpted the people in her family. It’s a loving testimony that pulls at our hearts.

With a trove of details and a lack of sentimentality, Tamari’s photographs, her artful clay reliefs, and elegant language knit together a world that could appear to be lost, but which continues to live in the artist’s creative fortitude. Tamari’s writing style — open, intimate, and expressive — is compelling and refreshing. It invites the reader not only into her own family story, but also into the broader Palestinian story of a bountiful life, filled with family outings and social gatherings, against the broader backdrop of the Palestinian story: that of grief, loss, courage, and resilience in the face of the Nakba and its aftermath.

In closing, the final words in Tamari’s Preface explore the “what ifs” of life, the lingering questions on every Palestinian’s mind — what would it have been if …? What would it have been like…? — powerful questions that haunt, but that also resurrect the past and bring it back to life if only through our imagination.

“Writing these stories has allowed me to contemplate and reflect on the personal reverie that since childhood has lingered in me: dreaming of how life would have been in Palestine, had we been spared the tragic loss of the land and the cruel expulsion of its people. What would it have meant had we been allowed to continue living normally in our homes, towns, and villages, and to prosper uninterrupted by war, occupation, and exile? Simply, what would it have been like had we been able to follow, both as individuals and as a nation, our rightful desires, and dreams? Although this book did not free me from my unattainable reverie, it helped transport me through a virtual, mental and emotional RETURNING to Jaffa and my lost Palestine.”

Vera Tamari, RETURNING.