MY TREE

directed by Jason Sherman

102 min. Hawkeye Pictures & Some Canadian 2021

It is a common reaction for those unfamiliar with settler-colonialism to be stunned by the harsh reality of Palestinians living under Israeli occupation. The greatest strength of the award-winning documentary My Tree (2021) directed by Jason Sherman is its unassuming nature. The film embodies how many people feel when they first learn about the human rights violations Israel has committed under the guise of achieving statehood. With nearly two hours of impactful content, My Tree forces the audience to consider the impact that settler-colonialism has on not only the people who are forcibly displaced by its violence, but also the environment that is altered by it.

Jason takes the audience on a journey of self-discovery to find the tree that links a person and a place together. In his childhood home in Toronto, Canada, during the 1970s, it was routine for Jason’s Jewish parents to make a modest donation to the Jewish National Fund (JNF). Accordingly, as part of his bar mitzvah, Jason was gifted a JNF ‘Tree Certificate’ announcing that a tree would be planted in his name in Israel. The certificate states, “For over 70 years, the Jewish National Fund has performed miracles in changing Israel’s swamps, desert, and rock beds into land on which farms and settlements have prospered.”

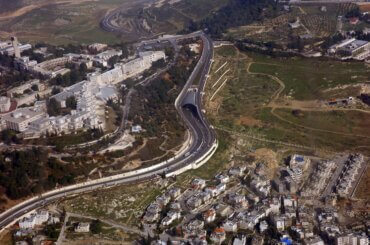

As an adult, Jason received little support from the JNF in his quest to learn about his “bar mitzvah” tree. Therefore, he decided to track down his tree on his own volition. During his search across Israel-Palestine, Jason discovers that the JNF was created to raise funds for settlement projects. “Blue Boxes” for donations were a tool to help promote the Israeli state. The first Prime Minister of Israel, David Ben-Gurion, supported this endeavor, famously commanding, “Cover every land with trees, make the desert bloom.” People from around the world became inspired to help change the desert ecosystem into forests. However, what contributors to the JNF didn’t realize is that the transformation of the landscape would displace Palestinian villages.

Since its founding in 1901, the JNF has planted over 250 million trees across nearly 250,000 acres in Palestine to solidify Israel’s rule over the land. An estimated 600 villages have destroyed since 1948. Ninety of these villages are buried beneath JNF parks, one of them named “Canada Park,” where Jason surmises that “his tree” was likely planted.

When Jason arrives in Tel Aviv, he wonders what his tree might have contributed to the developed ecosystem. What he discovers is the devastating consequences these JNF-planted forests have had on the land’s natural ecosystem. He also discovers a growing internal moral unease that seeks resolution, and it is this feeling that becomes the new focus of his quest.

During the film, Jason speaks with Ishai Schuster, a gardener for Kibbuts Mefalsim, and learns that the most commonly planted tree by the JNF is the Aleppo pine, Pinus halepensi—which can be detrimental to the environment if grown in large numbers. Pine has shallow root systems that make them unstable, and branches that consistently fall, damaging structures nearby. These trees also produce ample amounts of sap, which is extremely flammable. The risk of forest fire was horrifically demonstrated by the 2010 Mount Carmel fire that burned about 12,000 acres and resulted in the deaths of 44 people.

Recently, the film My Tree was used as a catalyst for conversation during an online film salon hosted by Voices from the Holy Land (VFHL) on July 16. The discussion was moderated by Iymen Chehade, an adjunct professor of Middle Eastern History at Columbia College Chicago and founder of Uprising Theater. In addition to Jason Sherman, the panel comprised Seth Morrison, treasurer for Jewish Voice for Peace; and Mazin Qumsiyeh, founder and director of the Palestine Museum of Natural History and the Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability at Bethlehem University.

Quimsiyeh, emphasized that the creation of Canada Park represents much more than a preference for pine trees, it is an effective weapon for enacting settler-colonialism. “Replacement theology in the colonizing context, of course, involves replacing the people and reshaping the landscape.” Quimsiyeh further explained that the JNF’s planting campaign is an extension of the 1948 Nakba. “[Israel] uprooted not only the towns, the homes, the people, but they also uprooted trees around those villages, both domestic trees and wild trees.”

Throughout the film, Jason is frustrated by JNF’s lack of support to help him in his search for his ‘personal’ tree. He wonders, ‘Why is it so hard to talk about trees?’ It isn’t until he meets with Eitan Bronstein Aparicio, the founder of Zochrot—meaning ‘we remember’—that he discovers the truth. Jason learns that Israel forcibly displaced and demolished three Palestinian villages—Beit Nuba, Imwas, and Yalu—to ultimately rename the location “Canada Park.” The pines planted in this park are part of JNF’s effort to cover up war crimes.

During VFHL’s July salon, Seth Morrison discussed his experience on the Washington, D.C. Board of the Jewish National Fund and why he publicly resigned from the role. Morrison explained that when he had initially begun working for the JNF, he was led to believe by colleagues that the organization was no longer dealing with Palestinian land. After learning that this was not true, he resigned and shared his experience with the public. Although he was removed from the Arava Institute for Environmental Studies and lost many friends, Morrison remains committed to his decision. ‘The only way to deal with Zionism is to directly oppose it,’ he said to the salon’s audience.

As the film persuasively discusses, JNF’s forests help Israel to avoid questions about the morality of establishing a settler state in a land that already had a thriving, indigenous population. As Aparicio explains, if those questions are asked then “you must question your very foundation.” This haunting statement prompts the viewer of the film to look internally and ask, “What might be my own hidden history, and how do I reconcile with those discoveries to support justice for others?”

Reconciling with his own hidden history, Jason speaks with Mohyeddin Abdulaziz, a Palestinian-American activist who grew up in Imwas before his family was forcibly displaced from their village by Israeli soldiers. Abdulaziz shares with Jason how he contends with the creation of Canada Park in the wake of his village’s destruction. ‘The thing that is much harder is that [visitors] come to have fun,” he references the park’s contributor plaques, stating, “And it’s there…the names [of the people] [who gave] money to celebrate my destruction.” Mohyeddin shares with Jason that he hopes one day they will be able to return to Imwas and build a new home for his family. “I hope that one day we’ll plant other trees together with our own will,” Mohyeddin says as he shakes Jason’s hand.

Voices from the Holy Land’s film salon on Jason Sherman’s My Tree allowed 300 registrants to talk with the film’s director and participate with an expert panel discussing the events surrounding the film. On September 10 at 3 p.m. ETD, VFHL will be hosting another online film salon titled “Erasing Palestine from U.S. School Curricula.” Register here.

A critical look at the JNF’s tree planting campaign from last year ( delete Haaretz cookies ):

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/2022-07-20/ty-article/.premium/an-israeli-hunk-cannot-conceal-the-jewish-national-funds-greenwashing/00000182-0c0b-d8f9-a7af-9f6b737b0000

If anything, the fund has always been less of an environmental group and more of an intimidating real estate tycoon. The JNF owns 12 percent of the country’s land and holds assets valued at 10.3 billion shekels. In 2020 alone it deposited 2.8 billion shekels from land sales – solely to Jews, of course. How can an organization with such a foot in the construction industry preach to us about green lungs?…The fund’s website contends that over 240 million trees have been planted in the JNF’s forestry project in Israel, contributing to the struggle against climate change and for quality of life and the environment. But in recent years, the JNF has been using tree-planting largely as a political tool for expelling Negev Bedouin from their agricultural land. It plants thousands of dunams of forest – in the middle of the desert, right? – “to block Bedouin from gaining control over the land,” as the fund’s chairman once said at a JNF gathering….The JNF is also an enthusiastic partner in the settlement enterprise – the largest suburbanization enterprise in the history of Zionism. It destroys the landscape in the name of Jewish sovereignty….Therefore, an organization that operates in the name of Jewish supremacy – and that discriminates, dispossesses and banishes anyone not Jewish – isn’t worthy of being called green.