Edward Said once asked, “Since when does a militarily occupied people have the responsibility for a peace movement?”1

To this I would add, “Since when do the victims of genocide have the responsibility to defer to and protect the feelings of those who enact, support, and enable their genocide?”

I have been thinking about this a lot since October 7. About how the Palestinian struggle for self-determination, life, safety, and justice is the site of convergence for debates around European antisemitism and the feelings of Australian Jewish communities.

I find myself asking: do Palestinian feelings — let alone lives — count? Which feelings are we being asked to hold space for in the context of a genocide against Palestinian people? Why is our advocacy for the basic right to survival constantly juxtaposed with reports about rising antisemitism and the fears and political anxieties of Jewish communities? Why is mention of Palestinian truths and trauma confined or downplayed to avoid offending Jewish Zionist sensibilities?

Why are the strategists who deliberately blur the lines between the ideology of Zionism and the Abrahamic religion of Judaism in order to weaponize antisemitism and shield Israel from criticism not held to account? Why are those who sit in the corridors of power and exhibit zero political faculty to distinguish between Zionism as a White European Jewish supremacist political ideology on the one hand, and Jewish people and the Jewish faith on the other, not called out?

Palestinians and their supporters who, amid the scourging of their homeland, the genocide of their people, the starvation and displacement of survivors, are expected to defer to the fragility of Zionists. We are seeing this play out across multiple sites and contexts — from protests to expressions of liberatory Palestinian nationalism, to political chants, to language and dress.

On October 7, Palestinian fighters broke out of their 16-year hostage conditions in the Gaza Strip, an open-air prison that the UN had declared “unliveable” and which every credible human rights organization in the world has variously described as criminal, in breach of international law, inhumane, illegal, a ticking time bomb, and a humanitarian disaster. Expressions of shock, surprise, and disbelief at Hamas’ unprecedented breakout and attack were symptomatic of the lack of attention to Palestine in the West, where military occupation— a daily crushing and asphyxiating violence— is treated as a kind of background noise or banal necessity, rather than conceived as the root cause of the violence of the so-called “conflict.”

Australia’s Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, and state Premiers rushed to condemn Hamas and assert Israel’s “right to defend itself,” dutifully lighting up iconic landmarks and buildings across Australia in the colors of the Israeli flag, including Sydney’s Opera House. Establishment media, politicians, and the pro-Israel lobby characterized Palestine rallies organized across Australia as an expression of hatred towards Jews; a “celebration” of Israeli deaths. Media reports quoted seasoned Zionist mouthpieces who described the protests as “compound[ing] the grief and suffering of Australia’s Jews.” Speaking about the protests on ABC radio in the tenth week of the genocide, proud Zionist Deborah Conway told Radio National Breakfast host Patricia Karvelas that she and those she knew in the “Jewish community” felt “wretched” that after enduring the “death-cult atrocities” of October 7, they had to “endure this extraordinary response from the community who decided that Israel just needed or the Jews just needed a bit more punishment.”

Privileging the emotional standpoint of settlers and colonizers goes somewhat further than the usual ‘both sidesism’ device that offers the false equivalence between occupier and occupied, oppressor and oppressed. It inverses the relational power dynamic such that the oppressor becomes the hapless victim, even as they drop weapons of mass destruction, destroy all semblance of civic life, and exact the lethal might of the Western military machine on unarmed men, women, and children. In this schema, there can, therefore, be no space for the claims, feelings, right to life, or humanity of the occupied and oppressed.

Palestinians who have been subject to Israel’s violent settler colonial apartheid system and military occupation for seventy-five years have never been afforded the solidarity of the Australian government to the point of condemning Israel for its genocidal violence. No federal or state government has lit up a building in the colors of the Palestinian flag to honor our thousands upon thousands of dead. We are denied the right to the status of victims of violence. Instead, our protests against state violence and militarism are delegitimized, and our cries, political demands, and analyses are denied space. Our liberation movement is framed through the distorted lens of Zionist racism that refuses to acknowledge the Indigenous people of Palestine and our political and historical claims to justice and restitution. Zionist racism reduces our cause to a religious conflict, a conflict with Israelis, because they are Jews, not because they are our oppressors, occupiers, and colonizers. Thus, a handful of outliers who briefly chanted antisemitic slurs at Sydney Opera House before being asked to leave by Palestinian organizers on October 9 were readily presented as the norm rather than the exception. For days after, as Israel pounded Gaza with weapons of mass destruction, killing thousands of people in their homes, rally organizers were aggressively interrogated in interviews about “how the Jewish community feels” rather than being afforded the space to speak of our grief, our trauma, our fears, our story.

Media reports quoted Jewish Australians expressing fear and feeling triggered in response to the rallies. Claims such as that “the Melbourne CBD is now a permanent no-go zone on Sundays for visibly identifiable Jews” or that the School Strike for Palestine aroused “fear” that Jewish students would be alienated and suffer “emotional harm” erase the presence of visibly identifiable Jews attending, organizing and speaking at rallies. The fact that such claims are not correlative with the facts on the ground—the strong, consistent messages denouncing antisemitism, the clear decolonial, anti-racism framing of speakers— is immaterial when the criteria upon which all Palestine advocacy is judged is the risk of Zionists being emotionally triggered by expressions against Zionist racism.

Denying a genocide, refusing historical context, vilifying claims to justice and self-determination, representing calls for a free and decolonized Palestine as an existential threat to Israel and all Jews, converts the symbols, language, soundscapes, optics and aspirations of the Palestine movement into triggers and offensive provocations. In her iconic book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, scholar and writer Sara Ahmed argues that emotive impressions attributed to people or things come to be shared because of how emotions circulate, accumulate, endure, and “stick.” Emotions circulate by moving “outside in,” meanings impressing onto objects. It is critical to interrogate how feelings are intertwined with material, political, and social relations of power. To reflect on how some feelings—no matter how objectively offensive, irrational, or self-serving they can be— can be validated, legitimized, and emboldened when people have been politically primed to defer to the feelings and interpretive filters of one group over another. The result is both dangerous and ludicrous.

Zionist claims that Jewish communities feel unsafe by the word “intifada” and chants of “Free Palestine” are thus read as “code for antisemitism” and accepted as ‘truth’ in mainstream discourse. Rather than interrogating the warped translations of Arabic words and contextualizing Palestinian expressions of freedom, Zionist feelings are privileged over clear-headed normative interrogations of a racist political ideology.

Award-winning journalist and founder of Media Diversity Australia, Antonitte Latouf, was just sacked from Australia’s national broadcaster, the ABC, for social media posts, including an investigative piece Latouf co-wrote for Crikey questioning the authenticity and editing of viral footage showing pro-Palestine protesters allegedly chanting “gas the Jews.” Despite reports raising doubts about the footage, the claims against Palestinian protestors continue to be made, and Latouf is now embroiled in an unfair dismissal claim for being punished for doing her job as a journalist.

At a public school in South Australia, a mural painted by an Indigenous artist containing the phrase ‘from the river to the sea’ (as well as other phrases including First Nations ‘Always Was Always Will Be’) was described as a “genocidal call” and “hateful and political stunt” “during a time of rising antisemitism,” “causing the Jewish community to feel unsafe.” Instead of accounting for the feelings and trauma of a people who are enduring genocide in real time, last week, the South Australia Education Department deferred to the ideology of a Zionist organization and directed the school to remove the phrase from the mural.

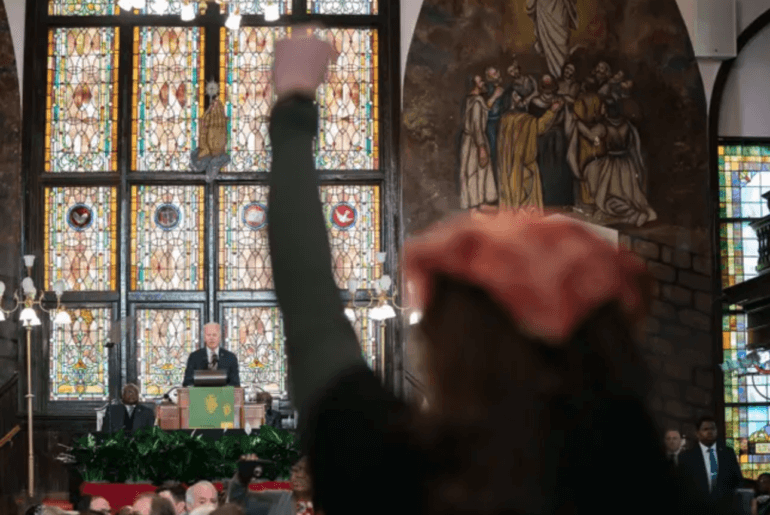

Last week, a photo of a family fishing boat painted with the phrase “from the river to the sea” and named “3Palstin” was posted on social media and condemned for “spreading the malignant cancer of antisemitism.” Last month, a man was asked to remove a Justice for Palestine t-shirt before boarding a Virgin Australia flight from Sydney to Melbourne because other passengers felt it was “offensive.” Last week, my friend, a young Palestinian woman, was wearing a keffiyeh-print hijab whilst shopping at a department store in Western Sydney. She was stopped by a staff member on her way out. The employee, standing beside an irate couple, told her that the couple felt uncomfortable and upset by her scarf as they shopped.

Last month, Jewish Zionists were “outraged,” “profoundly saddened and disappointed,” and felt their ‘safe space’ threatened and disturbed by three actors in a Sydney Theatre Company stage production who wore Palestinian keffiyehs during curtain-call. Donors withdrew, a petition garnered over 1000 signatures, one performance was canceled, three board members resigned, and the company went into a frenzy of damage control and issued statements of apology about “safe spaces,” “harm,” and “offense.” One board member resigned because there was “no apology from the artists” for a gesture that “traumatized Jewish members of the audience.” Resigning from the company’s philanthropic foundation in protest, another prominent donor Judi Hausmann wrote, “I never imagined my resignation would be necessary because I’m a Jew.”

In all these instances, expressions of Zionist fragility expose a calculated, purposeful strategy of insisting on the status of victim when confronted with the material fact of Palestinian existence and the solidarity of others. That the cultural presence of the keffiyeh on stage is enough to trigger Zionists in the audience and Zionist board members reveals how the fragility of Zionist privilege is being challenged at a moment of global awakening and reckoning of the genocidal violence of the colonial settler project. The keffiyeh, as a symbol of anti-colonialism and anti-racism, thus disrupts the Zionist narrative of victimhood and centers Palestinian resistance as a struggle for freedom and self-determination, supported by people across the world in their thousands, in their millions.

What is grotesque in the weaponization of Jewish ‘trauma’ over a symbol of cultural significance is the fact that at that very time, the Palestinian death toll from Israeli airstrikes and bombardment had reached over 15,000. It is now over 25,000. That a keffiyeh worn by an actor could be read as code for attacking and traumatizing Jews is only made possible by an expectation on the part of Zionists that arts elites (and indeed other spaces, too) will police and maintain the inequitable distribution of sorrow and solidarity. It is because of this expectation that there have also been fierce reactions to a clear shift amongst artists and arts workers in support of Palestine, not just in Australia but in other Western countries, too. The self-correction we are seeing towards the equitable distribution of empathy and solidarity from occupier to occupied has been distressing for many Jewish Zionists. Writing about her resignation from the STC foundation, Ruth Ritchie described her community feeling “ostracised” and “bewildered” “as the progressive left abandons traditional stalwarts and allies,” “our own cool group – the outliers, the artists, the big thinkers.” It is a sentiment expressed across ‘left’ spaces not only in Australia but in other Western countries where concerns are raised about Jewish people feeling ‘isolated’ on university campuses, for example.

The unprecedented mobilizations for Palestine that we are seeing across Australia, especially among Bla(c)k/Indigenous and diaspora communities, has been particularly difficult for liberal Zionists who express feelings of betrayal, ostracization, and abandonment from ‘the left,’ who have traditionally been counted as Zionist alibis and allies. Rather than admit that Israel’s genocidal actions have awakened more and more people to the historic struggle of self-determination of the Palestinian people and that political communities are recognizing the connections between regimes of violence and racial capitalism across settler colonies posturing as democracies, Zionists seek to center their feelings about losing sympathy and solidarity.

Over on Linkedin, Jewish Zionists have posted about feeling anxious and worried at work, consumed with thoughts about “the barbaric terrorist massacre that started this war,” the fate of Israeli hostages, and feeling “scared” in Australia for the “first time in our whole lives.” “We said ‘Never Again’,” says one post, “but is ‘Never Again’ now?” The poster longs to “get back to living my one life, the one where I’m at work and can just focus on work, and not worry about my safety, my kid’s safety and the safety of my people.” You can find many such posts across social media platforms. While I do not dismiss or downplay incidences of antisemitism or any form of racism, be it anti-Muslim racism, anti-Arab racism, anti-Black racism, or anti-Palestinian racism, how can any individual support an apartheid settler colonial state carpet bomb, drop white phosphorous, starve, and dehydrate a population of over 2 million people, murder over 20,000 people in just over two months, and still make it about your sense of safety and the safety of Israel as it executes a genocide? It is telling that to validate feelings of ‘unsafety’ is to accept that life was good pre-October 7. In other words, when occupation and the horrors of besieging Gaza are hidden behind a military blockade, Zionists like this poster did not have to think about we, the Palestinians, as humans with rights to safety and life too.

For Jewish Zionists, the shock induced by Hamas’ breakout and attack is compounded by a sense of rage and indignation that Palestinian fighters momentarily turned the tables, piercing through Israel’s years of military siege and occupation. This loss is what Judith Butler called in the 9/11 American context as “First World Presumption” or “first worldism”2 — “the loss of the prerogative, only and always, to be the one who transgresses the sovereign boundaries of other states, but never to be in the position of having one’s own boundaries transgressed” — arguably explains why Israelis were so quick to describe Hamas’ attack as Israel’s 9/11. It explains why the reflexive response, like the U.S. after 9/11, was to exact revenge not only for the Israelis killed or held hostage but for the colonized and the occupied to dare to fight back against the oppression; to dare to transgress the besieged boundaries of Gaza and claim freedom and life. In the words of one of Australia’s prominent Jewish Zionist leaders tweeting on October 7, “The attack is without precedent and now the response must be.” In the words of another: “flatten Gaza”. It is not only shock and indignation at Palestinians rupturing and resisting the status quo of siege and occupation that we are expected to tolerate and live under in perpetuity. Palestinians must also temper our language and be sensitive to the sensibilities of Jewish Zionists who call for our destruction.

This essay is but one among a volume of analyses that aim to expose what is unsaid in the public sphere. That Jewish Zionists demand Palestinians and those who support Palestinian self-determination be silent. That we collectively tolerate Zionist racism as a gesture towards atonement for the violence of European antisemitism. That we elide seventy-five years of violent occupation to assuage settler death and suffering on October 7.

Palestinians bear no responsibility to coddle the feelings of Zionist racists. We collectively refuse to provide Zionists with reassurances to placate and soothe their political anxieties.

My responsibility is to commit myself to the liberation of Palestine. I am confident that my fight against Zionism as a form of racism aligns with my unequivocal rejection and condemnation of antisemitism. I recognize the lethal and genocidal history of European antisemitism that produced the Holocaust and the destruction of European Jewry. I reject that because of European antisemitic racism, Palestinians must pay the price. I reject essentializing language, stereotypes, or theories that claim that there are particular traits or characteristics unique to “Jewish people” as a homogenous collective, or “being a Jew.” I defend the right of Jewish people to openly practice Judaism and freely express their religious and cultural identity. I defend the right of Jewish people to practice their faith even though I unequivocally reject and condemn Zionism as a political ideology. I do not accept that such a right can be enjoyed at the expense of Palestinian life, freedom, and self-determination.

No amount of intimidation or emotional blackmail will cower Palestinians into silence, into shrinking our voices, adjusting our language, compromising our demands and claims, or repressing our feelings. When the feelings and fragility of Zionists are used as a rhetorical shield to deflect from engaging with the moral and material reality of genocide, Palestinians are left to ask: how many of us must be killed, maimed and injured, forced from our traditional land and beloved homes, be tortured and have our schools, universities, and livelihoods destroyed, for those in power – those who have the power to stop this genocide – to say in public never again. Khallas. Enough.

Notes

1. “A New Current in Palestine” in Live From Palestine : International and Direct Action Against the Israeli Occupation, Edited by Nancy Stohlman and Laurieann Aladin 2003, p54

2. Butler, J. (2009). ‘Violence, mourning, politics’, in Harding, J. and Pribram, D. eds., Emotions: A Cultural Studies Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 387–402.

Randa Abdel-Fattah

Dr. Randa Abdel-Fattah is a Future Fellow in the Department of Sociology at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. Her research areas cover Palestine, Islamophobia, race, the war on terror, and social movement activism. Dr Abdel-Fattah is also one of Australia’s most prominent Palestine advocates, a former litigation lawyer, and the multi-award-winning author of 12 books published in over 20 countries and translated into over 15 languages.

I can almost, but not quite, feel a little sorry for those fragile Zionists. It must be hard to defend the indefensible.

And Australians, especially Aboriginal Australians, might find this bit of history interesting. A friend was working in Ramallah years ago, and an Israeli official said he was going to America to tour the Indian reservations, “to see how they do it.”

SHUN THEM!!!

It’s hard to see how you can write something like this and then deny with a straight face that you’re anti-Semitic.

The deck is stacked!

Regardless, a full house can beat a straight.

Winning entails calculation, playing cards well and understanding the game rules. Anyone can win or lose, depending on how well the game is played.

Fattah likes to demean Zionists by referring to them frequently in her diatribe as Jewish Zionists. What about Christian Zionists who feel the same as their Jewish brothers and sisters?

The <a href =https://plus61j.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Crossroads23_Survey_Report_June_2023_2-1.pdf>Crossroads23 survey</a> conducted in June 2023 indicates “a strong baseline identification with Israel: 90% agree that it is important that the Australian Jewish community maintains close ties with Israel, 88% feel a high level of personal connectedness with Israel, 86% agree that the existence of Israel is essential for the future of the Jewish people, 83% keep up with Israeli current events involving Israel and 80% indicate a high level of concern for Israel’s safety.”

Fattah’s attempt to drive a wedge between the small minority of so-called Jews, who keep bleating about the (self-imposed) plight of the Palestinians, is typical of the efforts by pro-Palestinian supporters to distinguish between good Jews, who support the Palestinians, and bad ones who are Zionists.

The fact is that the Hamas atrocity, which she disgustingly justifies, has brought the Jewish community closer together so that the anti-Zionist outliers are being seen more as pariahs.