On Tuesday, February 20, 2024, Mustafa al-Kurd returned to Jerusalem forever.

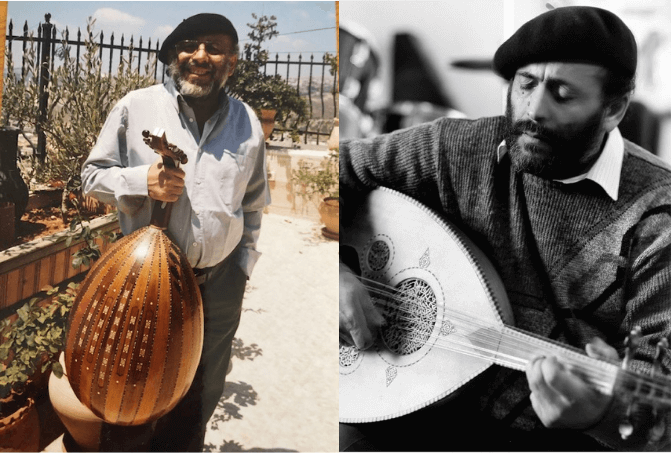

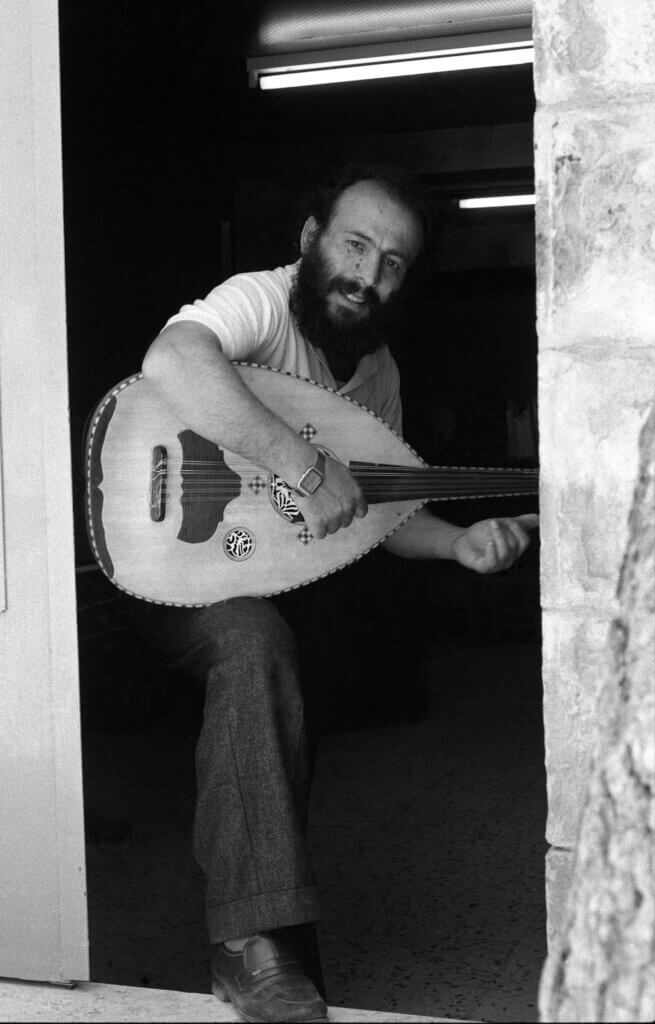

An oudist and a revolutionary, Mustafa al-Kurd’s music marked the first popular uprising (Intifada) of the Palestinian people against Israeli occupation. Born in Jerusalem in 1945, al-Kurd was too young to remember the 1948 Nakba (‘The catastrophe’) that would drain Palestine of its musical and cultural repertoire, but the 1967 Naksa, a second exodus (or literally “setback”) would determine his course permanently.

To understand his serious impact, one must understand the times. Al-Kurd started making music at a time when Palestinian society was trying to process and overcome two consequential tragedies. Palestinian identity, which was ironically flourishing during the British Mandate, had been completely razed in 1948. Almost all of the renowned Palestinian composers, like Rawhi Alkhammash and Yousef Khasho, had fled Israeli intimidation, and whoever remained in Gaza and the West Bank under Jordanian or Egyptian authority (at the time) was perhaps still at a loss. During the 50s and the 60s, most Palestinian musicianship was happening or being “imported” from the diaspora. On the inside, music was limited to Birzeit College (later Birzeit University) and a small wave of amateur rock bands or “rock formations” — as researcher Issa Boulos once called them. Mustafa al-Kurd, with only his voice and an oud, will help reset the compass.

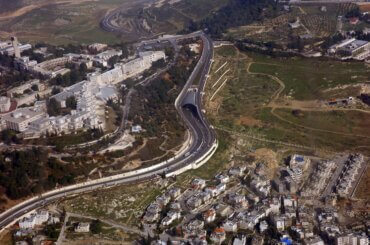

Having witnessed firsthand the occupation of the al-Musrarah neighborhood in East Jerusalem in 1967 (where Israeli-organized bus caravans transferred Palestinians to neighboring countries through the Jordanian border), al-Kurd’s music was a response to an urgent need to speak out. Singing his experience of living directly under Israeli occupation, al-Kurd used simple melodies and a clear Jerusalemite dialect. In a way, he would help push a new wave of “Palestinian liberation music,” or what would later be called “committed singing.” Having gained attention for his music, al-Kurd would be arrested multiple times by the Israeli military and placed under administrative detention. His first record, “Al-Ard Ardi/ Terre De Ma Patrie” (a collaboration with the Balaleen theater troupe he’d helped form), was produced in Jerusalem in 1974 and then published by French record label Expression Spontanée in 1976 after he was deported by Israeli authorities.

Al-Kurd lived in forced exile for nine years, where he would study piano and composition in Göttingen, and music ethnology at the Free University of Berlin. There, he continued making music and pressing vinyl. Al Kurd released Palästina, meine Liebe in 1977 for the German label plän, and the iconic La voix de la Palestine in 1979. Come 1980, he put out Ik Droom Van Morgen for the Netherlands Palestinian Committee. Al-Kurd’s discography serves as a direct manifestation of exile. When examined, his songs can provide a trace of his long journey in Europe and evidence of a “golden era” of global solidarity and struggle against colonialism and oppression. Being allowed to return to Palestine in 1984, al-Hakawati, the famed and still-standing Palestinian theater he would help establish, officially opened its doors that same year as an ode to al-Kurd’s return to Jerusalem.

On Tuesday, Palestine lost an oud virtuoso, a theater pioneer, a singer, a revolutionary, and a humble giant. When looked up online, not much information will show up on Mustafa al-Kurd besides his music. I, in my years living in the West Bank, have never personally met him nor come across him in town or within intellectual and cultural circles. I recognize I am a generation or two down the line and was not there for his active years, but I know that to recount the “intifada of the stones” is to recite Mustafa Al Kurd’s Hāt al-Sikkaih (“Give me the plow and sickle / And I will never leave the land.”)

Al-Kurd kept his word. As I understood, he spent his last few days in Jericho in the West Bank, shy of congratulatory parties, before returning, at last, for his burial in Jerusalem.