It was an ordinary Tuesday morning when Israeli forces arrived at Birzeit’s campus. The semester was drawing to its close. Students were still inhabiting the familiar, minor dramas of university life: the arithmetic of grades, the quiet panic induced by syllabi reread too late, the low-level guilt attached to courses in which effort had not quite matched ambition. These anxieties, rehearsed and recognizable, belonged to a calendar that assumed continuity. The morning, like most mornings, appeared to agree with that assumption — until it didn’t.

The soldiers entered with confidence. They were under direct orders to disrupt and induce some shock into the body of a university with a long history of tit-for-tat with Israeli military authorities.

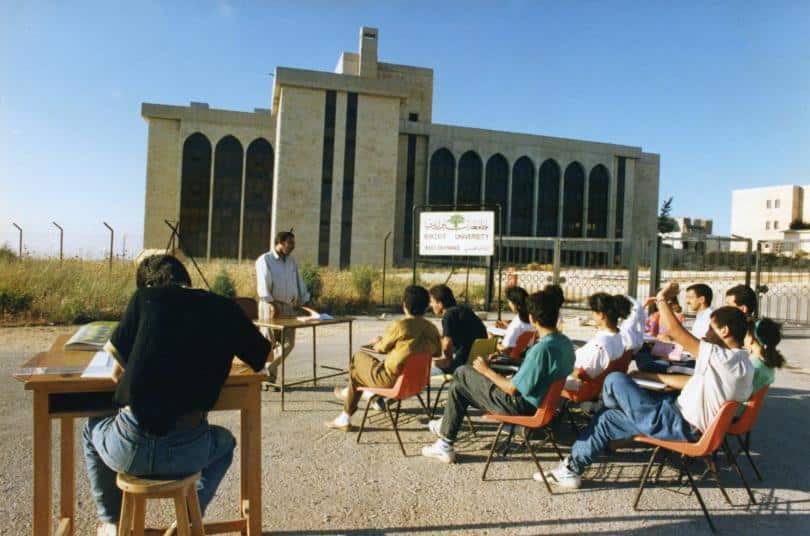

Birzeit had its golden age at the moment of its inception, or shortly thereafter. It lasted for a decade or two, depending on who is doing the remembering. It was an era defined less by institutional stability than by the university’s repeated closures by the Israeli military; classes reappeared in borrowed houses, in improvised rooms, in spaces whose chief qualification was that they could be made to disappear. Teaching became an exercise in logistics as much as in pedagogy, knowledge passed on under conditions that assumed interruption as the norm rather than the exception.

This period also marked the height of a certain collective confidence. The life of the university cohered around three constellations, mutually reinforcing and occasionally in tension: the teachers’ and workers’ union, the student movement, and the administration. Together, they produced a dense political and intellectual culture in which the university was not merely a place where education occurred, but also a site where arguments about autonomy, discipline, and the possibility of thinking in public under constraint unfolded.

This was the late 1980s, a moment suspended between rupture and unraveling. The First Intifada had brought with it a rare, combustible clarity, a brief and costly sense that collective action might still generate political meaning.

At the same time, the Palestinian national movement was beginning its long slide out of coherence, exchanging the language of mass mobilization for that of managed process. What followed would later be dignified as diplomacy, but already bore the marks of capitulation — what Edward Said called the “Palestinian Versailles” — prefigured in the habits of accommodation that would be formalized by the Oslo Accords.

The distance between street and leadership widened, and institutions like Birzeit found themselves straddling an increasingly unstable divide between popular legitimacy and bureaucratic survival.

The recent invasion of Birzeit did not so much inaugurate a crisis as make audible something that had been circulating for years as background noise. The conspicuous lack of response — hesitant, procedural, quickly exhausted — registered less as failure than as confirmation.

What occurred on campus named a condition long sensed but rarely articulated: that the university’s capacity to act as a collective political subject had been hollowed out in advance.

The incursion revealed not only the asymmetry of force that made resistance costly, but the thinning of the institutional reflexes that once translated shock into action. What followed was not outrage so much as administrative containment, as if the event were an inconvenience to be managed rather than a rupture demanding interpretation.

It has become difficult to deny that Birzeit is no longer what it once was. The transformation has been gradual and, therefore, easily rationalized.

It has become difficult to deny that Birzeit is no longer what it once was. The transformation has been gradual and, therefore, easily rationalized. Economic pressures have mounted; student numbers have swelled beyond the material and pedagogical limits of the campus; teachers and staff operate under conditions of chronic overwork, their labor stretched thin by the demands of accreditation, reporting, student numbers, and managerial compliance.

What was once a dense intellectual commons now resembles a corridor system, efficient and exhausted, designed to move bodies through requirements rather than ideas through minds. The result is not collapse but fatigue: an institution that still functions, but largely by default.

This stress point did not arrive unannounced. For years, the university has yielded to the logic of bureaucratic survival, trading the risk of intellectual confrontation for the safety of institutional continuity. In doing so, it has quietly relinquished an older ambition: education as a liberatory practice, capable of producing students attuned to their historical moment and equipped to intervene in it.

What remains is an education oriented toward credentialing rather than consciousness, management rather than meaning. The tragedy is not simply that Birzeit has changed, but that this change has come to feel inevitable — an adjustment to circumstances rather than a choice, and therefore one that rarely appears open to contestation.

When soldiers made their way onto campus, they were not only asserting power; they were, in a quieter and more unsettling way, reminding the university of what it had already become. The incursion had the quality of an exposure and a rupture, as if the institution were being confronted with its own reflection. What once required sustained coercion to suppress now appeared largely self-contained, disciplined in advance. The soldiers’ presence was almost redundant.

In this sense, the scene took on a faintly derisive tone. The intelligence officer’s posture — half-bureaucratic, half-performative — read less as menace than mockery. The university’s familiar claims to autonomy, to critical life, to interruption as a mode of thought, sounded hollow against an institution that had become expert at managing itself.

If the incursion exposed the university’s diminished capacity to name itself as a political space, the aftermath supplied the corroboration. A few weeks after the university was invaded, the student movement announced a strike. The university was shut down, and classes were canceled in protest. Yet it wasn’t over the army invasion, but something entirely different: the administration’s refusal to acquiesce to the student movement’s demand to move final exams online. The student movement’s strike did not arrive as a counterweight to humiliation — it was its continuation by other means.

The student strike is no longer politically meaningful

Historically, Birzeit’s student movement possessed a genuine capacity to strike: not merely to suspend classes, but to interrupt the political and institutional rhythms of the university, to force confrontation where accommodation was easier. Strikes once functioned as a language of refusal, calibrated to make authority visible by halting what it sought to keep seamless.

This time, the inherited form survived, but its content had shifted. Announced two weeks after Israeli forces threatened the university, the student movement demanded that exam finals be moved online, ostensibly as a way around the realities of checkpoints and the daily obstacles to reaching campus. Yet beneath this framing lay another, less articulated assumption: that, after years shaped by Covid and later by the genocide, online examinations had come to be accepted as a means of bypassing study altogether, rather than as a temporary concession to emergency.

In this sense, the strike is an excess rather than an intervention. It did not press against power so much as fold itself into the institutional logic it purported to contest, reinforcing a clientelist mode of representation in which the measure of politics becomes the delivery of immediate relief to students rather than the articulation of principle.

The student movement positioned itself as a broker between the students and the administration, between inconvenience and workaround, rather than as a force capable of reimagining the terms of the situation. And because the strike centred on assessment, it further confirmed the university’s prevailing hierarchy of values: that what must be safeguarded at all costs is the evaluative machinery, not the conditions of learning that once made evaluation meaningful.

The consequences were not merely symbolic. In encouraging the migration of exams online, the strike tacitly normalized a culture in which cheating is less a breach than an anticipated outcome, built into the solution’s design.

In a university already strained by overcrowding, exhaustion, and eroded trust, the move signalled, yet again, that assessment matters more than learning, and that results can be secured without responsibility. The point is not to moralize about students, who respond rationally to the structures they inhabit, but to notice what the episode reveals: a historically potent instrument of collective action redeployed in a manner that makes visible how far the university — and the movements within it — have travelled from the conditions that once made such action disruptive, and therefore politically meaningful.

What, then, does this culture of cheating really tell us? We should be careful not to treat it as a mere moral pathology, as if a decline in individual virtue were sufficient to explain what is taking place. Cheating is not simply a deviation from the educational process; it is increasingly its hidden organising principle. The point is not that students sometimes cheat, but that the system now functions as if cheating were already anticipated, even integrated. Education continues, degrees are issued, the ritual of assessment is preserved—but emptied of the very substance that once justified it. Knowledge no longer mediates between effort and outcome; it becomes an optional ornament, an ideological remainder.

This is where the deeper, more unsettling logic emerges. Cheating is not the negation of education; it is its obscene double. It allows the institution to sustain the fiction that learning is taking place while everyone involved tacitly acknowledges that something else is going on. The student doesn’t learn a discipline, but a skill more appropriate to the moment: how to navigate systems without inhabiting them, how to extract credentials while withholding commitment.

This is why online examinations are so seductive. They do not merely enable cheating; they formalize a relation to knowledge in which responsibility is displaced onto technology, circumstance, or exception.

But this is precisely why cheating should be read as a symptom of something more sinister. It signals not the collapse of education, but its transformation into a managed simulation of itself. The danger is not that students no longer believe in education; belief is no longer required.

What is demanded instead is compliance with procedure. In this sense, the culture of cheating is the truth of an institution that has already abandoned education as a formative, risky, and transformative experience. The scandal, then, is not that students cheat, but that the system can no longer tell the difference between learning and its performance — and no longer seems to care.

The impossibility of Birzeit

The point isn’t to merely critique Birzeit’s present condition, but to recognize its impossibility under the prevailing order. The university presupposes a certain wager that students can be formed as thinking subjects capable of producing, creating, and intervening in the world they inhabit.

This wager collapses when the world itself operates as a disciplinary apparatus that encourages the opposite. Students today are trained — systematically, and from multiple directions — not to think too far or produce beyond established templates. The tragedy is that they fail to rise to the university’s purported ideals at a time when the conditions in which those ideals might make sense have been methodically dismantled.

Living under a regime of terror sharpens this contradiction to the point of cruelty. Terror does not function only through spectacular violence; it disciplines through anticipation, exhaustion, and saturation. Subjects end up managing risk instead of imagining alternatives. Education as a space of experimentation becomes intolerable in this context, and thought itself begins to feel like a liability. The student learns, quite rationally, that excessive reflection does not protect you. Creativity and knowledge grant you neither immunity nor the ability to challenge power.

This is where the impossibility of Birzeit must be named honestly. Yes, it is besieged from the outside, but it is also rendered incoherent by a world that has already decided what students are for. The university is asked to perform its role — to graduate, to certify, to assess — while being denied the temporal, psychic, and political conditions necessary for education to mean anything beyond credentialing.

Birzeit is confronted with a crisis it can’t manage its way out of, because it is caught in a structural contradiction: how can it produce thinking subjects in a world organized to neutralize thought itself? That is the deeper violence of the terror regime: it doesn’t need to close universities outright if they can remain open only as shells, bereft of the very possibility that once justified their existence.

Perhaps one could conclude that this, too, is life in the West Bank today, organized around the capacity to cheat your way out of reckoning, out of anger, hate, and grief. This capacity to cheat is not only individual; it is collective. It sustains a machinery that continues to function even as everything around it announces the end of an epoch. Institutions remain standing, procedures remain intact, slogans remain available. What disappears is substance. One moves through the forms of politics, education, and even resistance without encountering their risks.

What remains becomes the tyranny of form: radical catechisms repeated without conviction and rehearsed without consequence. Form survives precisely because it no longer demands belief. We need to understand cheating not as a failure of ethics but a mode of adaptation to a world that has made sincerity dangerous and depth unsustainable. It is how you carry on when the horizon has collapsed, keeping the shapes of things intact even as their meanings quietly drain away.

Abdaljawad Omar

Abdaljawad Omar is a writer and Assistant Professor at Birzeit University, Palestine. Follow him on X @HHamayel2.