Photo of Ghazl textile factory workers in Mahalla in 2008. (Photo: Hossam el-Hamalawy)

The word ‘surreal’ has crossed many mouths since 25 January. Egypt—a country where the minimum wage is $7 a month—harshly criminalizes the incitement and organization of protest, and yet it is the cradle of the largest, boldest and most evocative demonstrations that anyone alive can remember. Socioeconomic diagnoses of the Middle East are completely sidestepped in most Western coverage of the region (though, to be fair, little in the way of class consciousness dares get stirred in domestic coverage too). There has been due attention on the unprecedented galvanization of Egypt’s modestly comfortable middle class, though it can’t be forgotten who or what brought them to the point of leaving their houses for the streets en masse, putting their bodies in the line of tear gas and live ammunition pelted (sometimes lethally) by Mubarak’s forces.

Spanish worker’s party poster: ‘Obreros ¡A la victoria!’ (Workers: To Victory!’), 1936.

The feelings generated by the ongoing revolt in Egypt—the revolt of the poor who’ve endured stagnant wages for decades, the revolt of the young who dare not hope for better economic prospects than their parents, the revolt of any Egyptian who seeks free and fair organization and expression, and on and on—is something I’ve only heard described in books. Specifically one book, Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, and the afterlife of the Spanish Civil War. Orwell described witnessing the ending of fascism as ‘that strange and moving experience.’ When he enlisted to aid people’s militias he hadn’t known that the war would end with radical self-governance, collectivized commerce and the disappearance of class divisions. The people had eviscerated, at least temporarily, not only the heavy foot of a torturous dictator but the conventional trappings of elitism. A passage from Chapter One is worth quoting at length:

I had come to Spain with some notion of writing newspaper articles, but I had joined the militia almost immediately, because at that time and in that atmosphere it seemed the only conceivable thing to do. The Anarchists were still in virtual control of Catalonia and the revolution was still in full swing. To anyone who had been there since the beginning it probably seemed even in December or January that the revolutionary period was

ending; but when one came straight from England the aspect of Barcelona was something startling and overwhelming. It was the first time that I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle. […] Every shop and cafe had an inscription saying that it had been collectivized; even the bootblacks had been collectivized and their boxes painted red and black. Waiters and shop-walkers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared. Nobody said ‘Senior’ or ‘Don’ or

even ‘Usted’; everyone called everyone else ‘Comrade’ and ‘Thou’, and said ‘Salud!’ instead of ‘Buenos dias’. Tipping was forbidden by law; almost my first experience was receiving a lecture from a hotel manager for trying to tip a lift-boy. There were no private motor-cars, they had all been commandeered, and all the trams and taxis and much of the other transport were painted red and black. The revolutionary posters were everywhere, flaming from the walls in clean reds and blues that made the few remaining advertisements look like daubs of mud.

It is extremely premature to think these wild, fantastical thoughts of a free society, and the experiment of Spain was so short-lived that Orwell ended up writing Animal Farm to allegorize the totalitarian period that followed. But compare Orwell’s accounts to today’s live report from Cairo by Democracy Now! producer Sharif Abdel Kouddous:

There is a great sense of pride that this is a leaderless movement organized by the people. A genuine popular revolt. It was not organized by opposition movements, though they have now joined the protesters in Tahrir. The Muslim Brotherhood was out in full force today. At one point they began chanting ‘Allah Akbar’ only to be drowned out by much louder chants of ‘Muslim, Christian, we are all Egyptian.’

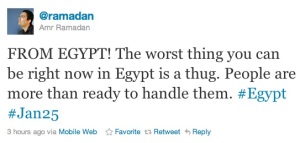

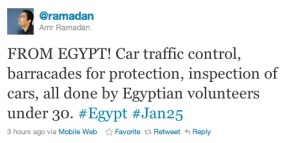

Meanwhile, across Cairo there is not a policeman in sight and there are reports of looting and violence. People worry that Mubarak is intentionally trying to create chaos to somehow convince people that he is needed. The strategy is failing. Residents have taken matters into their own hands, helping to direct traffic and forming armed neighborhood watches, complete with checkpoints and shift changes, in districts across the city.

I want to hope for something better than my own speculative imagination running amok. For Egypt’s precariously organized workers (and their supporters), a scenario of collective cooperation is not a pipe dream. It comes up in the last major published interview with Egyptian journalist Hossam el-Hamalawy (before the 27 January internet shutdown) in which he describes the origins of the worker movement’s struggle:

The Egyptian labour movement was quite under attack in the 1980s and 1990s by police, who used live ammunition against peaceful strikers in 1989 during strikes in the steel mills and in 1994 in the textile mill strikes. But steadily since December 2006 our country has been witnessing the biggest and most sustained waves of strike actions since 1946, triggered by textile strikes in the Nile Delta town of Mahalla, home of largest labour force in the Middle East with over 28,000 workers. It started because of labour issues but spread to every sector in society except the police and military.

[O]ne major distinction between us and Tunisia is that although it was a dictatorship, Tunisia had a semi-independent trade union federation. Even if the leadership was collaborating with the regime, the rank and file were militant trade unionists. So when time came for general strikes, the unions could pull it together. But here in Egypt we have a vacuum that we hope to fill soon. Independent trade unionists have already been subjected to witch hunts since they tried to be established; there are already lawsuits filed against them by state and state-backed unions, but they are getting stronger despite the continued attempts to silence them.

Unions have always been proven to be the silver bullet for any dictatorship. Look at Poland, South Korea, Latin America and Tunisia. Unions were always instrumental in mass mobilisation. You want a general strike to overthrow a dictatorship, and there is nothing better than an independent union to do so.

For Egyptians and their supporters outside of the country, the energy of the silver bullet has been contagious. This is a circulated video of Waseem Wagdi, an Egyptian at the Egyptian embassy in London. His emotional appeal is rife with class awareness:

We are here to show solidarity with the heroes on the streets in Egypt, we are here to show solidarity with the political prisoners in Egypt, we are here to show solidarity with the the workers who declared an open strike and a sit-in until bringing down the regime of Mubarak.

I had hoped, against all hope, [this] would happen in my lifetime. And I had hoped, and I think with millions of people, that our children will live in a more human society. But this society we have, lucky enough, that the heroes in Egypt are making today, they are not waiting for our children to dream, they are bringing all of our dreams true today. In Suez, the factories, in Meydaan al-Tahrir. The biggest square in the Arab world is being liberated today from this regime.

I’m proud of all Egyptians who are cleansing themselves of all remnants of fear, who collectively and singly have raised their head up high, and no one will bring it down again. No one.

When asked if he had a message to the people of Egypt, Wagdi looks directly into the camera for the first time, and recites the celebrated revolutionary poem ‘Unadikum’ (‘I Call Upon You’) by Palestinian Tawfiq Zayyad by heart.

… My tragedy that I live

Is my share of your tragedies

I call on you

I press your hands

I kiss the ground under your feet

and I say: I sacrifice myself for you

I did not humiliate myself in my homeland

and I did not lower my shoulders

I stood facing my oppressors

orphaned, naked, and bare foot

I call on you….

__________

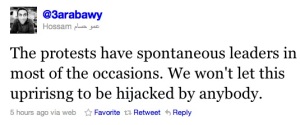

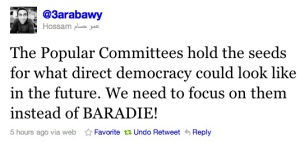

Update: Since posting this last night, many reports have been coming in from Cairo that substantiate the widespread collective organization of the Egyptian people self-securing on two fronts. They continue to defy curfew and attack by Mubarak’s forces (including an aerial provocation hours ago that saw at least two fighter jets flying very low to the people in Tahrir Square) by demonstrating in head-spinning numbers. In the sudden (and very creepy) disappearance of the police they have organized neighborhood patrols to defend their municipalities, families and private property. Here are some a collection of notable tweets from Egypt (of considerable value since the internet suspension), in ascending order of timestamp:

There’s no appropriate way to make abstract predictions without watching closely, but in the words of al-Jazeera English’s Ayman Mohyeldin (live on the air at 11:08 EST): ’ordinary people are standing shoulder to shoulder.’

Monalisa blogs at South/South.