The entrance to the mosque was black and ashen. On a nearby exterior wall the words “Arabs Out” were spray painted as a warning to the community of Umm el-Fahm in central Israel. The culprits of the early morning April 18th rampage were Jewish extremists; a couple from the settlement of Yitzhar was arrested last week, suspected of of helping out with the attack.

The “price tag” molotov cocktail hurled on the Abu-Bakr al-Siddiq mosque, which sparked a protest in Umm el-Fahm, has become one more symbol of the struggle Palestinian citizens face in Israel. (“Price tag” refers to attacks against Palestinians in revenge for actions by the state against settlements, though it has come to mean any hate crimes against Palestinians.)

Since 1948, when Israel was established, Palestinians who became citizens of the state have had to deal with an entrenched system of exclusion from land and community planning, home demolitions and surveillance and repression targeting those the state views as internal enemies. The hate crime attacks–which have sharply increased since April 2nd, when the army destroyed buildings in the Nablus area settlement of Yitzhar–are the most blatant manifestations of how Palestinian citizens are targeted. But the state’s policies run deeper than the outrageous violence that Israel’s leaders are quick to condemn. The dispossession of Palestinians for the benefit of Jews is institutionalized.

A week after the mosque attack in Umm el-Fahm, we drove up north to speak with residents of Wadi Ara, a region populated mostly by Palestinian citizens located in what’s known as the Triangle, a geographic area in the north of Israel bordering the West Bank. Our intention was to interview people about Avigdor Lieberman’s plan to transfer the residents and land in Wadi Ara–including Umm el-Fahm–to the Palestinian Authority in exchange for Israeli annexation of key settlements around Jerusalem. Residents of Wadi Ara are quick to condemn Lieberman. But a plan yet to be carried out is hardly the most pressing challenge for them. So instead of a deep dive into reactions to being targeted for transfer, we received a crash course in the larger struggle Palestinians face in a state self-defined as Jewish.

“Lieberman is the easiest thing to deal with, because Lieberman’s at least honest. He says, ‘we hate Arabs, we don’t like you, and we want you out of the country.’ That’s direct. So it’s easy to oppose Lieberman,” said Ahmed Zoubi, a former deputy mayor of Nazareth, a city just north of Wadi Ara with a large Palestinian population. “The problem with the Zionist plan is that they hide everything from the Arab citizens, and they do land theft in quiet ways.”

Zoubi was sitting with Ahmed Melhem, the head of Wadi Ara’s popular committee, in Melhem’s office in Ar’ara, a 20,000-strong town. Surrounded by maps of Wadi Ara and pictures of community leaders meeting with Yasser Arafat, the finer points of Israeli land discrimination were explained.

The roots of Israel’s land policies trace back to 1948, when Zionist militias destroyed or depopulated over 500 Palestinian villages. In the wake of the Nakba, Israel expropriated the vast majority of lands previously belonging to Palestinians. The 1950 Absentees Properties Law transferred the lands of those who became refugees into the hands of the state, while a 1953 land acquisition law delivered another 1.3 million dunams into the state’s hands.

These laws and policies have shrunk Palestinian areas in Wadi Ara.

Before 1948, Umm el-Fahm constituted 140,000 dunams. After Israel’s land expropriations were carried out, Umm el-Fahm was left with 12,000 dunams, according to Palestinian scholar Sami Hadawi. Ar’ara, too, has been hit hard by land confiscation. In 1953, Israel expropriated over 8,000 dunams from the village.

Moreover, with the agricultural fields confiscated in Wadi Ara decades ago, the state has moved on to expropriating scattered plots inside of the Palestinian villages. And Melhem said that 200 homes in Wadi Ara are currently under threat of demolition. When Israel targets homes or confiscates land, the always-bubbling conflict between Palestinian citizens and the state bursts out into the open, like in 1998, when the Israeli military confiscated land from Umm el-Fahm to use for training, which sparked clashes. Twelve years later, another confrontation between Ar’ara residents and Israel escalated after the demolition of a home. The army said that the home did not have a permit and was built outside the municipality’s borders. Residents of Ar’ara arrived to block the demolition, clashes broke out and the town declared a general strike in the aftermath of the chaos.

By curtailing the growth of Palestinian areas, new Jewish communities are able to flourish–a logic that explains Israeli land policy from 1948 to today. In 1991, Ariel Sharon, then the Minister of Housing, created the “Sharon Seven Stars” settlement plan. That policy called to erect satellite Jewish towns in Wadi Ara in order to engineer contiguity between Jewish areas in the north of Israel and in the occupied West Bank. And more recently, there was an attempt to expand the town of Harish for ultra-Orthodox Jews, whose high birth-rate makes for an attractive population to use to halt Palestinian areas’ growth.

In 2009, Ariel Atias, the housing minister who oversaw the move to import Haredim into Wadi Ara, was blunt about why he was incentivizing through tax breaks the ultra-Orthodox to relocate. “Bringing the haredi community to the Wadi Ara” is a “national mission,” he said. Arab expansion should be halted, he said, adding that it is a “national duty to prevent the spread of a population that, to say the least, does not love the state of Israel.” The plan ultimately failed, though, after Palestinians and their allies strongly protested.

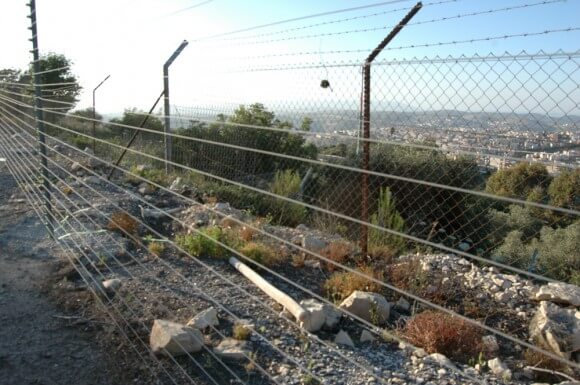

These national policies to confiscate Palestinian lands and transfer them for exclusive Jewish use can be seen from an overlook point near Umm el-Fahm in the moshav of Mei Ami. Named after the Florida city that financed the community in 1962 along with the Jewish National Fund (JNF), Mei Ami, meaning “our nation” and pronounced “Miami,” is the first of four localities now inside Wadi Ara that are called “settlements” by Melhem and other Palestinian neighbors. When the moshav was established, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency also called Mei Ami a “settlement,” despite the farming community’s location inside of the armistice line. This word “settlement” was carefully selected because in Wadi Ara these towns are, by law, for Jewish-Israelis only, on the hilltops and gated to the teeth.

Later “settlements” were established under Sharon’s housing plan in the 90s with funding from private entities like the JNF and the OR Movement, who specifically state that their mandate is to maximize Jewish controlled territory at the expense of Palestinian citizens of Israel. One of the newer towns, Katzir, became famous after a High Court decision ordered it to let a Palestinian resident live in the community, though it has never been carried out.

Today, densely populated Umm el-Fahm and Ar’ara have little room to grow because of Mei Ami and other Jewish-only towns that are built on their former lands. Palestinian lands that were taken in the 1950s are still being re-zoned for the purpose of ethnically-pure, fenced-up towns. The result is that Wadi Ara is not a harmonious mixture of Jews and Arabs, but a window into the low-grade conflict between Palestinian citizens and a state that ignores their needs.

Before we left the Umm el-Fahm mosque targeted by Jewish extremists, we asked the community member who showed us around–who didn’t want his name to be used–about the Lieberman Plan for transfer. He was opposed to it, and said, “We’re citizens of the country, not strangers in the country.” But Israeli policies flip that axiom on its head. Palestinian citizens are treated as strangers–not full citizens of the state.

Great report.

this is so surreal.

http://www.haaretz.com/opinion/.premium-1.590063#

“Justice Minister Zerah Warhaftig (National Religious Party) explained it quite bluntly during the Knesset hearing on the JNF Law in July 1960: “We want to make it clear that the Land of Israel belongs to the People of Israel. The ‘People of Israel’ is a concept that is broader than that of the “people resident in Zion,” because the People of Israel live throughout the world. On the other hand, every law that is passed is for the benefit of all the residents of the state, and all the residents of the state include also people who do not belong to the People of Israel, the worldwide People of Israel … We are giving legal attire to the regulations of the JNF.”

Great piece. This story should be on the front page of New York Times.

About price tags and a bit more about the Pope’s visit, today there is talk about a possible cancellation of the trip after threats were received that the Pope’s life would be in danger while in Israel.

Greek Orthodox Archbishop Atallah Hanna speaking for himself or officially for the church declared some outstanding political issues to be discussed by the Pope on his visit such as his displeasure at having Palestinians serve in the Israeli army. After he leaves Jordan, his first visit will be to the Dheisheh Refugee Camp in itself a political statement. He will meet with various Christian religious leaders as well as Muslim ones when he’ll stress that Christians and other Palestinians must not abandon the land, which blends-in with the subject of this piece by Allison and Alex. The Church of the Nativity is on the program as is a visit to al-Aqsa.

The interviewer tried getting a straight answer out of Archbishop Hanna on whether he was saying those things in an official church capacity or if he was speaking for himself but did not succeed. From the way the archbishop described it, the Pope’s trip to Israel is going to be very bumpy.

Apparently the Israeli government is worried about the safety of the Pope , something to do with the Last supper.

Holy See: Israel turning holy sites into military base ahead of papal visit

some 200 Orthodox Jews on Monday protested Pope Francis’ scheduled visit to an ancient Jerusalem site venerated by Jews as the location of King David’s Tomb and by Catholics as the setting of the Last Supper

http://www.haaretz.com/news/national/.premium-1.590256

all right, all right ….Jesus !

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VA1sx-vyWVk