As we approach the 70th anniversary of the Nakba, Americans have a lot to learn about the Palestinian catastrophe. Even if we consider ourselves well informed – and I include myself –we tend to have only a rough sense of what happened. Yes: More than 700,000 Palestinians expelled. Hundreds of villages destroyed. The massacre in Deir Yassin. Palestinians forced into the sea at Jaffa.

And of course we all have seen pictures of the processions of Palestinians walking east toward the West Bank as the land was cleansed.

But the storytelling of the Nakba here has been limited, and one thing that is missing is an appreciation of the culture that was lost. Without speaking Arabic, it must be impossible to comprehend the robust civilization whose destruction has been mourned by Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, Edward Said and Fouzi el-Asmar.

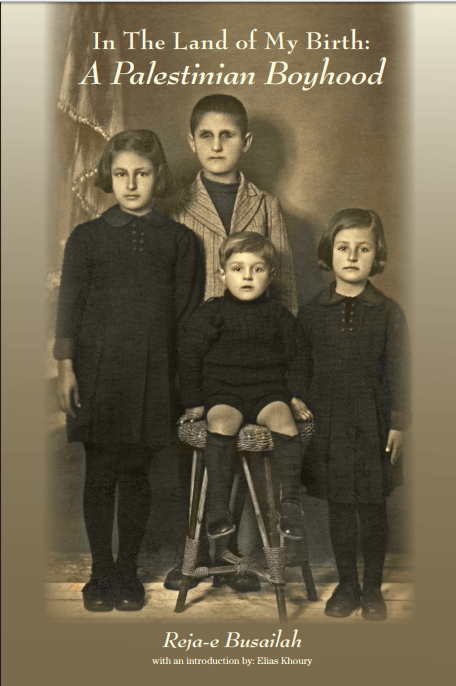

That is the majesty of this memoir that I have several times referred to in recent weeks. In the Land of My Birth: A Palestinian Boyhood.

Reja-e Busailah was a blind 18-year-old high school senior when he and his family were forced out of Lydda to the West Bank. He landed on his feet. He studied in Cairo then New York. He taught English literature for 30 years at Indiana University.

Yes, one of the lucky ones. But the achievement of his memoir is that Busailah has carried his anger at being made a refugee down through 7 decades and used it to etch a detailed picture of all that was lost when Zionists took over his land. In the Land of My Birth is a portrait of the scholar as a young man. His shelves are lined with Gibbon and George Bernard Shaw in Braille. He reads Shakespeare, Baudelaire, and al-Ma’arri in the monthly Arabic magazine Iqra. Like any good coming of age story, there are sexual discoveries and tales of abuse, but Busailah’s main interest is in describing the intellectual culture he had entered into in urban Palestine, a culture that was smashed to bits by Zionism.

As the Nakba begins, a friend asks to borrow Busailah’s copy of the French novel Paul et Virginie to take to Damascus. “Don’t worry, I will return it in two weeks,” Hasan Khateeb promises.

“I parted with my beloved book believing they would be back soon. I have never seen either him or the book since.”

By the end of this memoir, Busailah and his family have been uprooted, too, and we fully comprehend his sharpest resentment of the Zionists: they purported to represent a superior culture.

He burns with Churchill’s pronouncement that the expulsion of Palestinians was necessary to allow the implanting of a “higher grade race.”

“Of the boys and girls mentioned in this memoir, many were driven by ambition, dynamism, industry and energy worthy of any members of Mr. Churchill’s ‘worldy-wise race,’” Busailah laments. “They were full of hope and determination despite overwhelming odds.”

He is distressed that western readers would accept Yitzhak Rabin’s claim in his memoir that the removal of Lydda’s civilian population was reluctant on Israel’s part and that Israeli soldiers fired warning shots to effect it. No: he describes a noose tightening around the city as it empties, then mortar fire from the neighboring Jewish town, and raiding soldiers. “It was a time of inexpressible fear,” he tells us. “After the massacres on the road between Lydda and Ramleh, at the Municipal Square, and in Dahmash Mosque, the people were forced out of their homes and marched away.”

It still cuts at Busailah that The Nation in 1989 published an account of the emptying of Lydda saying that the residents simply fled. “Here [the militias] smashed a window, there they killed a chicken.” Busailah sputters, “Chickens, cows, donkeys!” — as if animals were the chief target.

I understand his rage. This was a truly existential experience for him. Alone in the house, he held out as long as he could not believing that the Jews really were as strong as the Arab resistance.

The final moment seemed very close, the moment of facing the longtime enemy, for most people the enemy from childhood, for many the enemy from birth. There had never been a genuine Palestinian leadership in the sense of something to rally around, something to entrust with higher, if vague, responsibilities, an authority that would give guidance and directives in times of crisis. It was as if each individual were almost the entire chain of command. Now, everyone, had to face both the present moment and the future alone, a host of atoms united only in their sense of panic and helplessness, unified by invisible ties to face an implacable enemy. The ‘flood of gold’ is upon us!

The blind youth was among the last to leave Lydda and walk to the West Bank in a flood of refugees, coins hidden in his underclothing. The expulsion has defined his life; and his precision reminds the reader of the tone of Holocaust testimonies.

Of course, Nakba histories are generally considered credible only when they come from Israeli writers. Yitzhar Smilansky, for instance. Benny Morris, Ilan Pappe, and Ari Shavit. Shavit revealed the ethnic cleansing of Lydda to The New Yorker readership five years ago, and then to scores of synagogues that he visited to sell his book, My Promised Land, saying that the Lydda expulsion was regrettably necessary to establish a Jewish state.

Busailah has a different view of the matter: it was a historical crime, never accounted for. There is no better way to convey his achievement than to quote passages that speak for themselves, two of them involving violence and mental illness.

First, a portrait of a high school classmate:

Mutee’ Amir was funny and lighthearted. He loved poetry and he liked to shock. He loved to tease me by reading poems with sexual allusions. I liked to hear the poems and I pretended to be shocked. He was very popular among the students. He had a good heart– better, some thought, than his mind. He was quite happy-go-lucky. But he had more than his humor. He studied with us at Ramleh high school and moved with us to al-‘Amiriyya in Yafa.

Later his name would be announced on the radio on the list of those who had passed the matriculation exam. I was surprised and delighted. Not much Later his name came up again. Shortly before the fall of Lydda he was shot between the eyes in a trench at dawn when the Jews overran his village. They said his mother was never in her right mind afterward.

Next, a portrait of a friend who visited a store that Busailah frequented because the storeowner was one of Busailah’s many readers-aloud, on whom he depended.

Haj Sa’id al-Hnaidi was another regular at Mustafa’s store. We called him al-Zatmeh, someone who clings to you until he gets what he wants, like a tick…. He was in his forties or fifties. He was big and very heavy, probably you would say obese. Khalid Abu Khalid used to call him “the hill of flesh.” He always came to borrow books. He was an avid reader, though somehow I doubted if he understood all he read. All the same, he would snatch the book from your hand and would not return it until he was done with it. Often he would run off with your book before you had a chance to look at it yourself. Once he saw me come to the store with Taha Hussein’s Hadith al-Arbi’a’, which I had just purchased from Suhwail’s bookstore. Al-Zatmeh wouldn’t even wait for Mustafa to look at its table of contents for me. He snatched the first volume and ran out of the store and began reading while he was still crossing the street. A boy on a bike ran into him. He fell with his great bulk in the middle of the street and blamed the incident squarely on me, because, he said, my book had prevented him from paying attention to anything else. Yet al-Zatmeh had a very amiable disposition. You couldn’t help but like him. I was shocked and saddened later when I heard of his death. He was, they said, marched out of Lydda by the Israelis with the rest of us. Although he endured the ordeal, soon after he fell into a deep depression and died.

And a third portrait. His father had been a vigorous teacher. Now he was living on relief in Ramallah.

For my father, and for tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands like him, this new life was inconsistent with their sense of dignity.

You will not find more penetrating descriptions of the Nakba than these portraits. When Jews speak of the destruction of eastern European Jewish culture in the Holocaust, well– this followed. And again, I study Palestine: but I did not appreciate the culture that was swept away.

Many injustices are documented in In the Land of My Birth: A Palestinian Boyhood. The one that is most present is the absence of Busailah’s voice in the American discourse. This masterpiece of the Palestinian experience was published last fall by the Institute for Palestine Studies, with a splendid introduction by Elias Khoury, and though it is getting some attention, it’s all in the margins. Busailah lives in Indiana; he did a Facebook event with the Educational Bookstore in East Jerusalem. One can only hope that the Jewish Israeli authors who have gained renown from their accounts of the Israel-Palestine story will be forced at last to share the stage.

P.S. The picture on the cover of the book is the only photograph the Busailah family has from his childhood. “Everything else was lost in the war and left behind,” Reja-e Busailah says. “Mother or Father saved this picture.”

Good article, Phil.

Thank you, Philip, for bringing Busailah’s intelligence and integrity to life in the few quotes you included. I love his centrality and full presence in the narrative. I just ordered my copy. Perhaps I will review it for Mondoweiss.

Just received from a Canadian friend:

https://www.facebook.com/IJVcanada/videos/1993511354001544/?hc_ref=ARQreMFpoCMdfacjAyVZSk4l3cFhnpNQCWc0p6FdtfeJljDR7S_JYx76J3_pbBcScPE

Independent Jewish Voices Canada (IJV)

Video of May 11/18 IJV online discussion regarding the role Canadians played in the 1948 Palestinian Nakba.

Very nice.

The photo is worth a thousand words.

A “must purchase” for me to read and reread!