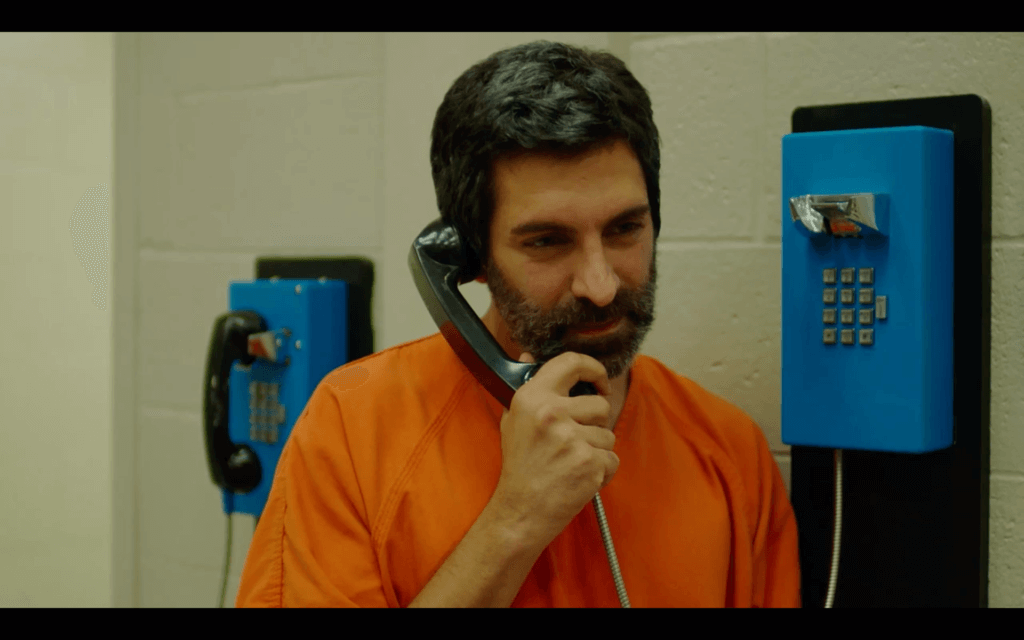

Marjoun and the Flying Headscarf will be making its online and international premiere on July 14. Set in Little Rock in 2006, it tells the story of a 17-year-old high school student fighting for her father’s release from prison, a struggle that leads Marjoun to a deeper understanding of her own identity.

I spoke writer/director Susan Youssef, who began developing the movie as a film school student during the aftermath of 9/11. Originally released as a short film 14 years ago, Youssef detailed the decision to expand the project years later, how her personal background shaped her vision, the evolution of Arabs and Muslims in American films, and the significance of her movie being released amid mass protests.

You released “Marjoun and the Flying Headscarf” as a short film in 2006 and now you’ve expanded it into a feature film all these years later. Can you explain the process? Was this always a project you wanted to come back to?

Susan Youssef: I did. I wrote it 15 years ago. I was also to the age of the daughter when I wrote it and now I’m close to the mom’s age. When I wrote it, it was right after 9/11 and it was also right around my first trip to Palestine as well. And it was very fresh in my experience, living in Lebanon under occupation.

So I was having a lot of different experiences in the beginning of my film career as an Arab-American with my identity and I was watching the optics of it shift around me with the way that other young women were expressing themselves. This was the 2000s. This is the beginning of the Arab-American community undergoing a deep evolution. I think in some ways it’s been extremely positive for us — if you look at the amount of media representation that we have today, 10 years later — but it was also deeply painful.

I wrote the short and I made it as it seems, a student poem, and I screened it first in Beirut, and the Toronto Film Festival. And then at the request of some friends, they told me I was crazy, not submitting to Sundance because they thought it was good. I threw it in….this was so long ago that I threw a VHS tape into an envelope and even I didn’t put it in bubble padding. I thought for sure it would be rejected and I totally forgot about it. I was totally expecting a rejection letter because there was nothing like it on TV.

I just thought it would just be ignored, but somebody loved it and to be honest, I was terrified. I was in the Netherlands working on Habibi at the time and the day I was going to fly to Sundance, I was sitting in my tiny apartment in the Netherlands crying. I think the discrimination was living inside me and I didn’t know how to show myself. And shockingly, when I went to Sundance, the great director, Alexander Payne, found me after a screening and told me he loved it. And Film Sales, which is a really reputable production company and sales representation company, called me and said, please send us the feature script.

I thought, there’s no way the first Arab-American or Muslim American feature can have a girl in it, going through deep identity crisis as a teenage girl like all teenage girls. It’s too soon. It can’t be this movie. So I shelved it and I ignored it. But it eats away at me, especially as time went on. I made Habibi and did what I needed to do with that, but there was still nothing like this movie. And even now, there are less than five Arab-American feature films made and that’s why this process took so long. I needed to create a safety in my identity for myself and also a feeling that I understood the climate around me. And that’s why the film is also set in 2006. It’s not me now. It’s made very much looking retrospectively at our position, us. I think I only truly got the courage to make it after I made Habibi because I express myself as an Arab filmmaker. And then I sort of understood and had more faith in myself to produce a film that was Arab-American and basically working in a brand new genre.

Five years ago, as part of the Kickstarter campaign for this film, you wrote that “it’s my project as a filmmaker to intervene with complex, positive, alternative, alternative images, especially of women.” Can you talk about how your personal background shaped that vision?

I’m exploring three generations in the film, exploring a young girl who was only nine years old, a teenager, and a young mother. I think I really wanted to create a world in which the women relied on each other because that’s my experience. If you look at the the great Arab directors, many of them are women. So I don’t necessarily believe that our culture is structurally strictly patriarchal.

I looked at this family structure that felt very familiar to me. I have sisters, I have a mother. And I started working with identities that I understood. But I also knew that creating a world where the women could rely on themselves or the young woman could ask the world around her to respect her would be virtually impossible.

Marjoun wants to run the store on her own. She truly believes it. And that’s the anchor of the film, it’s that desire to run the store and be autonomous, work autonomously to support the family. It’s also from my personal experience. We had a store, but my mom never worked. She was never educated. She came from a challenging background. It wasn’t that her father didn’t support her. It was the society and the way things functioned that were challenging for her. But that did not stop my family from changing the way that the rules were for me. And if you look at Marjoun’s family, they are trying to support her the best they can, but the evolution of the family is working too slowly for her.

You alluded to this earlier but we’re seeing more discussions about the way that race is tackled within our culture, including depictions within movies and television as a result Black Lives Matter protests gripping the country right now. I’m wondering what you think about the current state of Arab and Muslim depictions in film compared to when you first became involved in film.

I think for me, the fact that I am even aware now that I have some overlaps with African-American history, that’s a sign things are changing and there’s now a language for that. I didn’t understand that initially. You can go to the Gaza Strip and meet Black Palestinians, but there wasn’t a language to explore what that meant. There were just people that were darker than you. You just never saw them as different. They were just part of the community. They looked a little different and you probably understood that their ancestry was different.

At the same time you have people like my sister, who has blonde hair and blue eyes and it’s the same kind of intrigue, right? Right. Both are very exotic. I’m the norm and then you have two different ends of the same (as corny as it sounds) rainbow. I have to be honest, I still have a bit of a broken heart when it comes to how long I’ve been working now.

In 2006 I began my career professionally and where have we arrived? I had a talk with Dr. Evelyn Alsultany, who is a professor of Arab-American studies at USC. I called her and I was like, “Oh my god, this show Ramy [a Hulu series that follows a first-generation American Muslim] is doing so well, look how far we’ve come!” and I was also talking to her about the struggles with this feature. She implored me to not give up. There’s still not a show called Susan. It’s still a boy’s club. For women, it still hasn’t caught up yet.

The process of making the film wasn’t necessarily just difficult because of money. That wasn’t the only difficulty. It was also access and resources to build a project and to find the road for the project. But I do believe that right now, even though we had to rush it because of COVID, I do feel this is being released at the right time. Like I said, there wasn’t a language for me before to understand the overlaps in my culture.

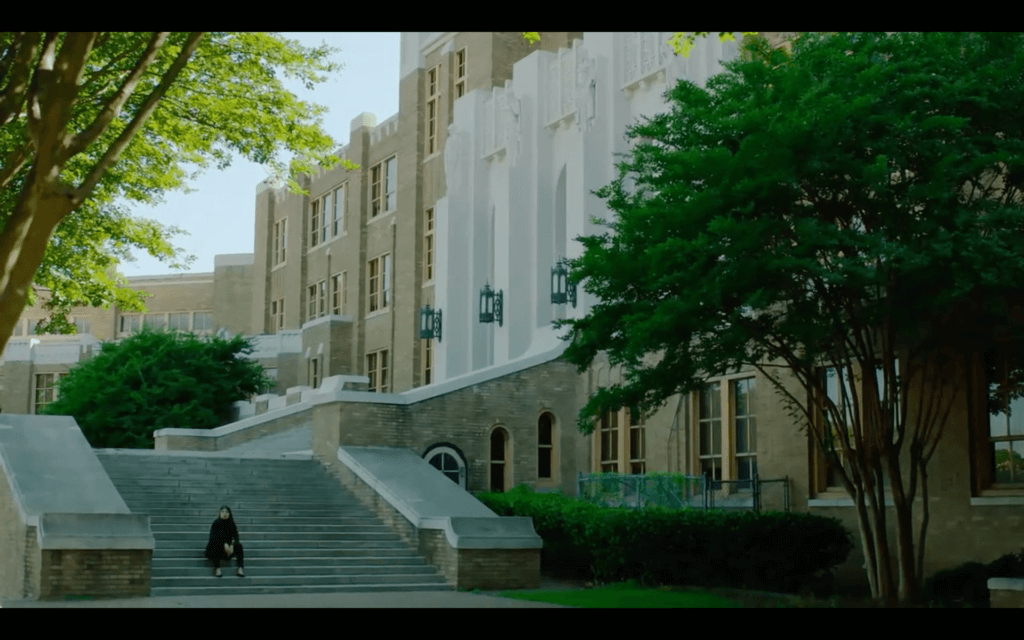

It took me two years to write because I was figuring it out. I had to go to Central High School [where the movie was filmed]. I went outside of the high school and there was a little girl in a hijab and a little girl who was Chinese-American. My husband was with me and he’s Chinese. We looked at each other like, “Oh, we’re supposed to here.” But we didn’t have the world to configure the project prior to this, we were kind of creating.

I do believe that it is getting better and easier. Ramy is an example. But, yes, it needs to catch up for women as well and the amount has to increase. We have one show, one! We had discussions about the limitations around this movie because it embraces faith, it’s a faith film. What are the limitations in discussing faith?

The movie centers around a family where the father is in jail on terrorism charges and it’s implied that they’re dubious. There were obviously a lot of cases like this after 9/11 as a result of the Patriot Act, but you don’t see the human toll of them portrayed on film very often. Could you talk about your decision to make a case like that, such a large part of the film and was there any case in particular that inspired the character?

So going back to the original question about what took so long to make this film. Why did it take almost 15 years? My original feeling was, we can’t just make this Arab-American or Muslim American feature about this teen in a hijab struggling with personal matters in the home because there’s no context for it. There’s no world for it. Arab-Americans and Muslim-Americans are suffering deeply. They’re being detained and harassed and there’s no language to discuss it. There’s articles here and there, but where’s the movement to protect people? I started reading articles about people like Dr. Sami Al-Arian and also Seyed Mousavi. And I was meeting young people, even in my personal life, experiencing things which were deeply traumatic.

Even when we presented the film, I’ve been really moved by people telling me personally, “Oh my god, something like that happened to my family. I don’t want to talk about it publicly, but it happened to me.” It happened to so many people and they were scared to talk about it. People were just so afraid.

I had a talk with Richard Pena, a professor at Columbia University, about cinema in 2012 after releasing Habibi, when I was immediately moving straight into Marjoun. He said, “First, there’s The Battle of Algiers and then there’s the rest of Algerian cinema.” You make nationalistic cinema first and then it can become more humanistic and personal in the narrative. I felt there had not been yet that first step of nationalistic Arab-American cinema. So Marjoun for me was both my cry for human rights, but also my understanding that I had to begin to put down the tapestry for this world. I felt it was important to build a school that explores human rights. That’s also the basis of how I do my work. I want activist depictions because I’m interested in challenging not just the stereotypes, but also evil forces such as occupation and the fact that we are experiencing our own form of civil rights struggle here that needs to be addressed.

Marjoun for me was both my cry for human rights, but also my understanding that I had to begin to put down the tapestry for this world.

Susan Youssef

This actually just leads directly to my final question. We’ve been talking about how this movie has been a long time coming, but at the same time, it’s just amazing that it’s being released in this moment in our nation’s history. We are seeing massive protests over the police murder of George Floyd, but also racism more broadly. The school you use in this film is the school of the Little Rock Nine, which was presumably intentional. What does it mean to you, to have the movie released at this time?

My husband and I moved to Little Rock for seven months knowing that there is very little film community. The more cinematically astute thing would have been to live in Austin or another film city like New Orleans and just shoot at a school on location, but I felt very much like I needed to experience the depth of layers of the human experience in that part of the world for people of color. Especially since Arkansas at the time had put a ban on the entry of Syrian refugees and my mom’s from Syria.

So I made a decision that made the film harder to make, and harder to finance, but allowed for a solidarity which I really craved for with the community. And it allowed me to bond with the community such that eventually I was able to have access to the school.

When I was thinking about a teenager, I was thinking of a teenager on the outside of society, trying to save her dad from imprisonment. And I thought about the most aspirational high school in American history. It’s obviously for me the high school of the Little Rock Nine, nine children that despite a mob went to school.

We almost delayed this premiere actually until September 25th, honoring the Little Rock Nine, but we felt the movement right now might need this film, because not everybody can go to protest. A lot of people are at home because of COVID. We thought it might be a beautiful time to have this discussion in the heat of summer and if we wait until September, we’re getting closer to the election and maybe it’s too late. So we felt, let’s just honor that legacy, and that legacy has been so important for me because I look back at the Arab and Muslim Americans coming to the U.S. as slaves from Morocco.

Nothing in this film was an accident. We went to a very tense and long-term grassroots casting process for the lead actress. And we happened to find this amazing actress who is Moroccan-American and I didn’t intend that. I always felt, wow, this is so wonderful because we’re honoring the first immigrants that came and they were Moroccan slaves. So, fits beautifully in the film as just from her own talents.

The last piece that we haven’t talked about yet, but it’s really important to me is that I visualized that Marjoun at one point would have to be rescued by somebody, some other outliers. I had written about the Buddhist nuns and part of the reason why I did that was because in my work to become stronger as somebody aspiring to support human rights, I did a lot of studying of Thich Nhat Hanh and his relationship with Martin Luther King. Martin Luther King was very essential to the Little Rock Nine succeeding.

I wrote that Marjoun would run away with monastics and I happened to find out as soon as I got to Central High School, when I started practicing with the Buddhist community there, that a monastery had been established in Mississippi in 2005, which is the year I started making the short. So it was just this amazing synchronicity that allowed me to work with them in the film. And they’re also now a part of our events, striving for healing and peace at this time. So, the film was embracing Islam, Christianity, Buddhism and obviously art.

My closest mentor in the entire film was executive producer Shari Springer Berman. And the film was really a production between me, an Arab-American born in Brooklyn and her, a Jewish-American born in Brooklyn, but we happened to make it in Arkansas. So I feel the film has succeeded in creating unity as a production. I truly hope that at this time, through our events, that we create unity.

The film will be available to stream on July 14. You can buy tickets here.

I’m so looking forward to finally seeing this film after all these years (first reading about it here on MW in 2015). It’s the perfect timing for the premier. After all these years of getting email updates on the film this is the first time I realized the connection with the high school in Little Rock, amazing. Congratulations to Susan, it’s been a long time coming.