MYTHOLOGIES WITHOUT END

The US, Israel, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1917-2020

by Jerome Slater

512 pp. Oxford University Press. $29.95

This excerpt from the Introduction of “Mythologies Without End: The US, Israel, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1917-2020” by Jerome Slater is reprinted with permission from Oxford University Press. The book is available for purchase on November 2, 2020.

Every nation has a narrative or stories about its history that are instilled into its citizens, generation after generation. The narratives explain much about a nation’s motivations, policies, and actions. In order to understand why nations behave as they do, then, it is essential to know what they believe about their history. However, no matter how sincerely and deeply held, national narratives often—perhaps typically—are misleading or simply untrue, embodying as they do mythologies that cannot stand up to serious examination and which, therefore, may be disastrous both for the peoples who believe in them and to others who are affected by them.

In what has become a cliché but nonetheless invaluable, Daniel Moynihan famously observed: “Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts.” Perhaps in no other major international conflict has the gap between opinions—or “myths,” as in this context I shall call them—and demonstrable historical facts been as great as they are in the Arab-Israeli and the Israeli-Palestinian conflicts since the early twentieth century. As a result, perhaps in no other international conflict have these myths, which still dominate Israeli and US political discourse, had such devastating consequences for both peace and justice.

In 1973, Abba Eban, the eloquent Israeli diplomat, said: “The Arabs never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity,” an argument—better said, a myth—that was widely accepted and continues to have a huge impact on how the Arab-Israeli conflict has been understood in Israel, the United States, and most Western states. But that assessment was wrong then, and wrong since—if anything, the converse is close to being the case. One of the central purposes of this book, then, is to correct this myth, both in the interests of historical accuracy and in an effort to pave the way for policy changes in Israel and the United States.

Since the creation of Israel in 1948 there have been some fourteen wars or at least major armed clashes (as well as many smaller ones) between Israel and Arab states, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), and the Islamic militant movements of Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza. These include the 1948, 1956, 1967, and 1973 wars, principally with Egypt and Syria; the 1978, 1982, 1993, 1996 and 2006 attacks against Hezbollah and the PLO in Lebanon; and five major Israeli attacks against Arafat and the PLO in the West Bank and Hamas in Gaza (2000–2001, 2002, 2008–9, 2012, and 2014). In addition, for more than fifteen years, the Israeli blockade or “siege of Gaza,” as it is widely called, has amounted to economic warfare.

None of these wars and lesser conflicts, probably even the 1948 “Israeli War for Independence,” were unavoidable. Israel’s independence and security could have been protected had it accepted reasonable compromises on the four crucial issues of the Arab-Israeli and Israeli-Palestinian conflicts: a partition of the historical land of Palestine; Palestinian independence and sovereignty in the land allotted to them in the 1947 UN partition plan, including Arab East Jerusalem; the return of most of the territory captured from the Arab states in the various wars; and a small-scale symbolic “return” to Israel of some 10,000–20,000 Palestinian refugees (or their descendants) from the 1948 war.

The historical record, examined in detail in this book, demonstrates that it has been Israel, far more than the Palestinians and the leading Arab states, that has blocked fair compromise peace settlements. As a result, the conflict has continued for some one hundred years, making it one of the world’s most important and, at times, most dangerous unresolved international conflicts.

The overall Arab-Israeli conflict can be seen, paradoxically, as one of the world’s most difficult, yet simplest international conflict to resolve. By definition difficult, since after a century it still hasn’t been settled. On the other hand, the solution is obvious and has been widely understood from the onset of the conflict, even by many and sometimes most of the participants. Two peoples, each having historical, religious, and political claims to the same land are locked into endless conflict: What can be done? For at least seventy-five years, study after study, international commission after international commission, negotiations after negotiations, have come to the same, nearly self-evident conclusion: the land must be divided between the two peoples on an equitable basis: the “Two State Solution.”

There is another paradox: precisely because it has gone on so long and is so potentially dangerous, the Arab-Israeli or Israeli-Palestinian conflict is one of the most studied international conflicts—by historians, political scientists, psychologists, journalists, and in the extensive memoirs and analyses of former political and military leaders. Yet it continues to be misunderstood, especially by the Israelis and their supporters, largely because their dominant historical narrative is the product of mythologies that are misleading or flatly wrong.

According to the conventional Israeli narrative, the story Israelis tell themselves and others, the Arab-Israeli conflict is the consequence of over a century of Arab hatred of the Jews and of their unwillingness to agree to numerous Zionist, Israeli, and international efforts to reach a fair compromise over the historic land of Palestine, starting with the Palestinian and Arab state rejection of the 1937 British Peel Commission compromise plan and, especially, the 1947 United Nations (UN) partition plan.

The UN plan provided for the division of Palestine between the Jews and the Arabs and the creation of the state of Israel. In a spirit of compromise, the Israeli narrative holds, the Zionist leadership accepted the UN plan, but the Palestinians and the neighboring Arab states rejected it and in 1948 launched an unprovoked invasion designed to destroy the new Israeli state.

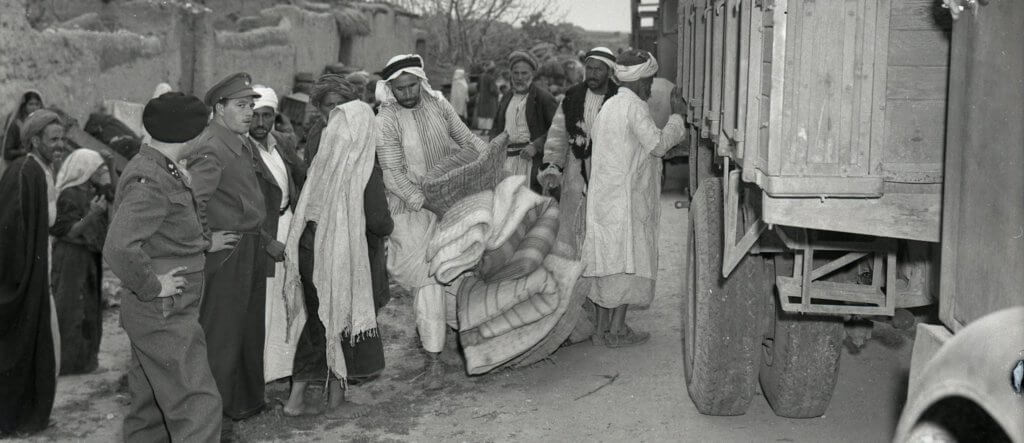

In the course of the ensuing war, the narrative continues, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians living within Israel’s boundaries fled to the neighboring Arab states, ordered or urged to do so by the invading Arab armies, even though the Zionists opposed the Palestinian exodus, hoping to demonstrate that Arabs and Jews could live side by side in the Jewish state. Thus, it is charged, it was the Arab states and the Palestinians who are responsible for creating the still-unresolved Palestinian refugee problem that, along with other issues, continues to block a two-state settlement.

After the 1948 war, the story continues, Israel remained willing to settle the conflict on the basis of generous compromise, but it could find no Palestinian or other Arab leaders with whom to negotiate. Consequently, the narrative holds, the conflict escalated into the Arab-Israeli wars of 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982, all begun or provoked by continuing Arab rejectionism, terrorism, and unwillingness to live with the Jewish state of Israel.

As well, the refugee issue remained unresolved, largely because it suited the cynical purposes of the Arab states to keep it festering, so as to undermine the security and viability of the Jewish state. As a result, with the aid of neighboring Arab states, especially Egypt and Syria, the Palestinians turned to guerrilla warfare and outright terrorism.

The wall of monolithic Arab hostility was not breached, the Israeli narrative continues, until Anwar Sadat of Egypt decided to make peace with Israel in the late 1970s, followed fifteen years later by King Hussein of Jordan. But even today, it is contended, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is no closer to being settled because the Palestinians still hope to destroy Israel rather than accept a fair compromise settlement.

So goes the Israeli narrative. However, while there are some elements of truth in it, most of it does not stand up to historical examination. Though other Israeli mythologies will be examined, especially those concerning Zionist ideologies, the primary focus of this book will be on the many lost opportunities for peace in the hundred-year conflict, and it will argue that it is Israel, not the Arabs, which has “never missed an opportunity to miss an opportunity.” Unwilling to make territorial, symbolic, or other compromises, Israel has not merely missed but sometimes even deliberately sabotaged repeated opportunities for peace with the Arab states and the Palestinians.

1 of 2

Thank you Jerome Slater!! Your book is “right on the money.!!” And thank you Mondoweiss for publishing this article!!

For the record:

What happened in Palestine in 1947 and 1948 was aptly described by eye-witness Nathan Chofshi, a Jewish immigrant from Russia who arrived in Palestine in 1908 in the same group as Polish born David Ben-Gurion (real name, David Gruen):

“…[W]e old Jewish settlers in Palestine who witnessed the flight [know] how and in what manner we, Jews, forced the Arabs to leave cities and villages…some of them were driven out by force of arms; others were made to leave by deceit, lying and false promises. It is enough to cite the cities of Jaffa, Lydda, Ramle, Beersheba, Acre from among numberless others.” (Jewish Newsletter, February 9, 1959).

Chofshi was deeply ashamed of what his fellow Jews did to the Palestinians: “We came and turned the native Arabs into tragic refugees. And still we dare to slander and malign them, to besmirch their name. Instead of being deeply ashamed of what we did and of trying to undo some of the evil we committed…we justify our terrible acts and even attempt to glorify them.” (ibid)

In 2004, when asked by Ha’aretz journalist, Ari Shavit, what new information his just completed revised version of The Birth of the Palestinian Problem 1947-1949 would provide, historian Benny Morris replied: “It is based on many documents that were not available to me when I wrote the original book, most of them from the Israel Defense Forces Archives. What the new material shows is that there were far more Israeli acts of massacre than I had previously thought. To my surprise, there were also many cases of rape. In the months of April-May 1948, units of the Haganah were given operational orders that stated explicitly that they were to uproot the villagers, expel them and destroy the villages themselves.” (Ha’aretz, January 9, 2004)

“…there is no room for both people together in this country…. The only solution is a Palestine…without Arabs. And there is no way than to transfer the Arabs from here to the neighbouring countries, to transfer all of them; not one village, not one tribe, should be left.” (Yosef Weitz, My Diary and Letters to the Children – in Hebrew, Massada, 1965, ll, p. 81) (cont’d)

2 of 2

John H. Davis, who served as Commission General of UNRWA at the time: “An exhaustive examination of the minutes, resolutions, and press releases of the Arab League, of the files of leading Arabic newspapers, of day-to-day monitoring of broadcasts from Arab capitals and secret Arab radio stations, failed to reveal a single reference, direct or indirect, to an order given to the Arabs of Palestine to leave. All the evidence is to the contrary; that the Arab authorities continuously exhorted the Palestinian Arabs not to leave the country…. Panic and bewilderment played decisive parts in the flight. But the extent to which the refugees were savagely driven out by the Israelis as part of a deliberate master-plan has been insufficiently recognized.” (John H. Davis, The Evasive Peace, London: Murray, 1968)

After studying the IDF Intelligence Report, “The Arab Exodus from Palestine” dated 30 June, 1948, document, Morris stated that “the Intelligence Branch report…goes out of its way to stress that the [Palestinian] exodus was contrary to the political-strategic desires of both the Arab Higher Committee and the governments of the neighboring Arab states. These, according to the report, struggled against the exodus – threatening, cajoling, and imposing punishments, all to no avail.” (Benny Morris, “The Causes and Character of the Arab Exodus from Palestine: The Israel Defense Force Intelligence Board Analysis of June 1948: Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. XXII, no. 1, January 1986)

Ami Ayalon deals with mythological narratives and opportunities Israel missed in his book “Friendly Fire”. Page 268;

We’ll never make peace…until we change the narrative about the past and admit to ourselves that the Palestinians have a right to their own country alongside Israel, and on land we claim as ours.

It seems to me the Zionist “myths” are more accurately termed “lies”. The entire Zionist narrative on the founding of Israel is a giant, easily disproven lie. They are willful falsehoods, part of a criminal cover story. Therefore – what other Zionist narratives, used to justify Israel, are also giant lies?

Each has historical, religious and political claims to the land, you say. But are they equally valid? It’s hard to see how they could be, since that would imply a right against right, truth against truth situation. Even harder if we start setting the detailed historical and religious claims side by side and assessing them one by one, precept upon precept, line upon line. All of us here know how every little point of the past is disputed. Your claims about missed opportunities will in their turn be disputed. If the two sets of claims are not equally valid it is hard to see why or how they justify equal rights to a share.

Perhaps it’s true that there come moments when all the argument has got nowhere and we are indeed in a situation of right contra right, of moral paradox, when we just have to move on and draw a line under the past. The Karabakh problem.perhaps? But I wouldn’t be too sure that the logical next step is what all those great, good, wise people have been calling for – the elusive 2ss. Israeli and Zionist opinion, as far as I can see, thinks that the logical next step is to accept that ‘we’ve won’, that the Zionist set of historical, religious and political claims is no longer worth disputing and that everything must follow from that. They say this over and over. Meaning that there will be no Palestinian sovereignty in any corner of Palestine and that if some Palestinians remain it is by grace and favour. Zionism has always considered itself generous and humane, so grace may be plentiful. But it isn’t a 2ss. As to logic of what happens when you’ve drawn a line under moral dispute they may be right.