Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from The Red Deal: Indigenous Action to Save Our Earth, a new book by The Red Nation which connects the struggle to prevent ecological collapse to the struggles against imperialism, capitalism, and settler-colonialism, including in Palestine. As The Red Nation summarizes: The choice is decolonization or extinction.

The United States owns the deadliest and most funded military power in the world. It invests more in its military than the next seven largest military powers combined. The US military also owns more international military bases than any other country.

Why does the United States invest so heavily in its military? The answer can be found in the creation of US settler sovereignty, forged through war against Indigenous nations. In its early years of existence, the United States needed free land to repay war debts following its war of independence with Great Britain. Looking westward from its original settler colonies to find this land, it created the first federal administration of Indian affairs office within the Department of War in 1789 to negotiate treaties with Indigenous peoples to take land in “fair trade.” However, when Indigenous peoples refused to sell their land, George Washington and the United States were ready to wage war, or in Washington’s words, to “extirpate” Indigenous people.

These efforts failed, largely because Indigenous nations were more powerful than the thirteen states at the time. The fledgling US government waited until another opportunity arose some thirty years later to attack these nations and gain control of their lands. This time it was through legalized theft. The most belligerent of these laws, the Marshall Trilogy (1823–1832), unilaterally changed the status of Native nations from foreign nations—their status according to treaties—to colonized subjects of the United States. Between 1823 and 1832 the US Supreme Court’s first Chief Justice, John Marshall, as Diné geographer Andrew Curley states, “defined the status and rights of Indigenous nations within the United States as ‘tribes,’ uncivilized peoples dependent on it and subject to its complete authority.”4 Drawing from the Doctrine of Discovery to justify the domestication of Indigenous nations, the Marshall Trilogy fabricated laws to alienate aboriginal title and strip Indigenous nations of their independence.

The Marshall Trilogy demonstrates how the foreign status of Indigenous nations posed an existential (as well as material) threat to the United States, which had already proven its intentions for vast territorial, political, and economic expansion. As the original foreign nations in the way of US expansion, Indigenous nations thus had to be terminated by any means necessary. Legalized theft was used alongside treaties and military campaigns (which included starvation, imprisonment, massacres, and scorched earth policies) to force termination.1 Its assault on Indigenous nations shaped the United States’ first decades of existence, not only giving birth to what we now know as the United States, but also defining its very existence. Although not thought of as such, the colonization of Indigenous people by the United States was, and continues to be, a project of imperialist invasion.

The Indian Wars never ended; the United States simply fabricated new Indians—new terrorists, insurgents, and enemies—to justify endless wars and endless expansion.

In her 2007 book New Indians, Old Wars, Dakota scholar Elizabeth Cook-Lynn defines US treatment of Indigenous nations as a quintessential form of imperialism: “a national policy of territorial acquisition through the establishment of economic and political domination of other nations.”2 She notes that wars today are driven by the same “colonial aggression and imperialistic nation building” as the wars of old.3 “If there is one policy behind the scenes that links the Iraqi experience of the twentieth century to the Lakota/Dakota Sioux experience of the nineteenth,” she writes, “it is the policy of imperialist dominance. Trampling on the sovereignty of other nations for most of its several centuries of nationhood has been the legacy of the American Republic’s power.”4

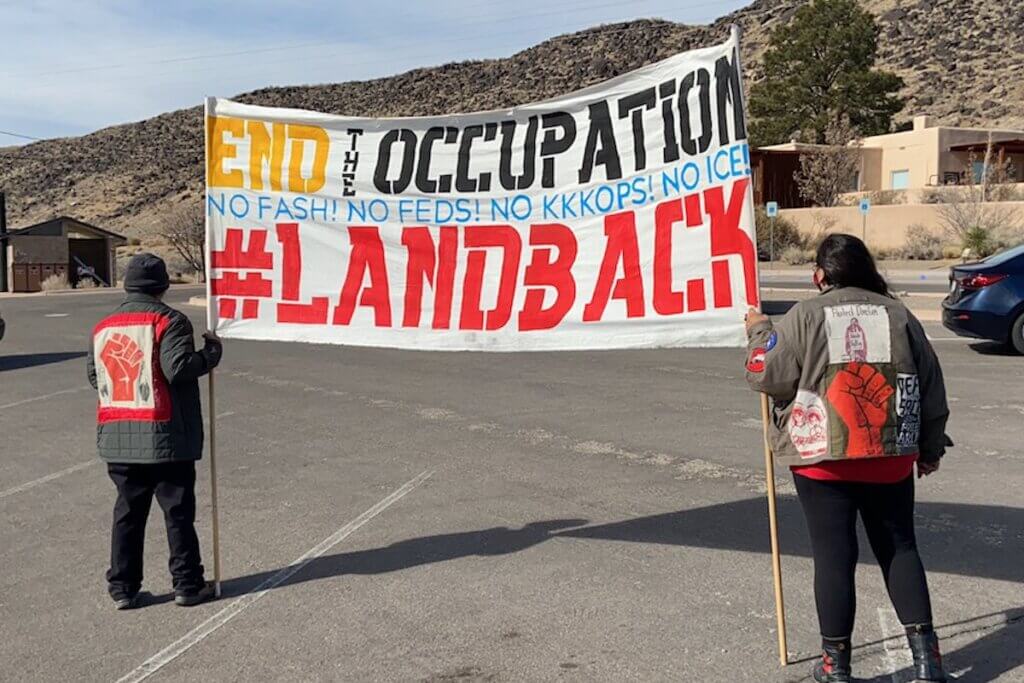

The original imperial violence enacted by the United States through Indigenous genocide and colonization in North America continues to this day, all in the name of natural resources, territorial positioning, and profit. Look at Standing Rock in 2016 when Indigenous people defending their treaty lands against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline were brutalized by the National Guard, which was sent in to detain and assault water protectors and land defenders. Look at Hawai‘i and Mauna Kea where Kanaka Maoli—Hawai‘i’s Indigenous people—continually face violence from the US military, along with being arrested by police for protecting their sacred sites. Look at Venezuela, which is under sanctions for refusing to cave to US bullying for oil. Look at Palestine, surrounded by two of the largest US military aid recipients, Israel and Egypt. Look at Okinawa, where in early 2019, tens of thousands of Japanese citizens called for the closure of US military bases. Look at Guam. Look at Vietnam. Look at Bolivia. Look at the Philippines. Look at Afghanistan. Look at Iraq. The Indian Wars never ended; the United States simply fabricated new Indians—new terrorists, insurgents, and enemies—to justify endless wars and endless expansion.

Our struggles for sovereignty and self-determination are the oldest anti-imperialist struggles against the United States.

In order for humanity to live free from this violence, we must center the decolonization of Indigenous nations and dismantle all laws, bombs, guns, sanctions, banks, corporations, social customs, and agreements across the globe that perpetuate US imperialism. Only then can we truly achieve liberation and justice for Indigenous nations in Turtle Island and for all oppressed nations across the world living under the boot of US domination. This means that advocates for Indigenous decolonization in the Global North must have strong analyses and an uncompromising stance on US imperialism. Our struggles for sovereignty and self-determination are the oldest anti-imperialist struggles against the United States. We owe it to our kin in the Global South to remember that our struggle for liberation is the same struggle they face.

We must unite against our common enemy. We have much to learn from one another. Our Indigenous relatives and comrades who gathered in the spring of 2010 in Cochabamba, Bolivia to draft the revolutionary climate document, the People’s Agreement, remind us that US imperialism does not happen only through laws and war- fare. Imperialism wreaks havoc on the world through capitalism. It keeps resources in the hands of a few while the rest of humanity starves and the Earth dies. Drawing upon ecofeminist, ecosocialist, and Indigenous principles and knowledge as tools to combat climate change, the People’s Agreement is a pact from the Global South and social movements that centers the needs of the majority of the planet, calling for an end to capitalism rather than maintaining the hyperconsumption of countries like the United States.

Ending the occupation everywhere thus means centering an effective and principled approach to climate change.

Because the burden of US-driven climate change has been externalized to the Global South (and Indigenous people specifically), the People’s Agreement makes the case for enforcing climate debt, and names the special responsibility that the United States—among all other developed countries—has for paying this debt and other reparations for its imperialist violence. Ending the occupation everywhere thus means centering an effective and principled approach to climate change, thereby releasing the burden from Indigenous nations and placing responsibility where it belongs. To this end, we urge people in the United States to organize campaigns that enforce the following demands for developed countries listed in the People’s Agreement:

- Restore to developing countries the atmospheric space that is occupied by greenhouse gas emissions. This implies the decolonization of the atmosphere through the reduction and absorption of their emissions.

- Assume the costs of technology transfer needs of developing countries arising from the loss of development opportunities due to living in a restricted atmospheric space.

- Assume responsibility for the hundreds of millions of people that will be forced to migrate due to climate change caused by these countries, and eliminate restrictive immigration policies, offering migrants a decent life with human rights guarantees in their countries.

- Commit to a new annual funding of at least 6 percent of GDP to tackle climate change in developing countries. This funding should be administered free of conditions and should not interfere with the national sovereignty or self-determination of the affected communities and groups.

Organizing to implement these demands can also be viewed as a form of divestment and reinvestment. As the People’s Agreement notes, an annual funding pool to repay climate debt that is comprised of 5 percent of the US’ GDP is “viable considering that a similar amount is spent on national defense, and that five times more has been put forth to rescue failing banks and speculators.”5 What if we created a system where the funds spent on imperialism in the form of defense and bank bailouts were redirected to heal the Earth by decolonizing the atmosphere and building a dignified future for our relatives in the Global South? This is not simply a question to ponder. It is a life- or-death program we must take seriously.

The United States is holding the rest of the world hostage, denying dignity to billions of people, and literally killing the Earth. Not to mention that US imperialism makes it impossible for other nations to practice basic self-determination or make any meaningful gains when it comes to climate change without constant interference and aggression from the United States, which usurps and thwarts any efforts it perceives to be against its own selfish interests. Only until we embrace anti-imperialism as the heart of our movements for Indigenous liberation will we be able to call ourselves true relatives—good relatives—to our kin in the Global South. We should start by organizing campaigns and movements to implement the People’s Agreement.

Reprinted from: The Red Nation, The Red Deal: Indigenous Action to Save Our Earth (Common Notions, 2021) www.commonnotions.org

Notes

1. Scorched earth campaigns were one of the weapons used by European colonial settlers and US military forces in their wars against Indigenous people; i.e., the destruction of villages, food stores, crops, livestock, and wildlife were used to undermine Indigenous resistance to colonization.

2. Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, New Indians, Old Wars (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007), 72.

3. Cook-Lynn, New Indians, 71.

4. Cook-Lynn, New Indians, 72.

5. Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, “People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth” (Cochabamba, Bolivia, April 2010).