Experiencing and remembering Palestine is different for all Palestinians. While the Palestinian right of return is by far one of the most unifying concepts in the Palestinian diaspora, the different experiences of Palestinians abroad is testimony to the fact that Palestinian narratives are varied and equally valid.

Chile is home to the largest Palestinian community in Latin America, with many Palestinian immigrants finding a home there since the late 1880s. The country also became a destination for Palestinians in 1948 during the Nakba, when Zionist paramilitaries ethnically cleansed Palestinian towns and villages. Another wave of immigration occurred in 1967 following the Six Day War, when Israel’s military occupation became entrenched and settlement expansion became a major political tool employed against the Palestinians.

For Palestinians who have not experienced the Nakba, remembering Palestine strikes a different chord. Depending on their arrival in Chile, Palestinians’ memories and those which are inherited through oral tradition may or may not include the 1948 Nakba. Yet the attachment to Palestine remains, despite the immigration trajectories, or exile. Lina Meruane, an award-winning Palestinian-Chilean writer, spoke to Mondoweiss about her connection to Palestine and how both Palestine and Chile have influenced her writings.

Can you describe your family’s ties to Palestine?

My grandparents on my father’s side came to Chile as children, in the 1900s. My grandfather was around 13 years old, and my grandmother was around six. Both of them came from Beit Jala but met in Chile, where they eventually formed their own family. They only thought of returning to Palestine in 1967, but the war broke out and they never did.

The family house is still there, only it’s no longer in the family’s hands. The descendants of my grandfather’s eldest sister still live in Beit Jala. I have visited them twice, but communication is difficult, because of language differences. I don’t speak Arabic, while they speak little English and no Spanish. Regardless, we have always been aware of our family’s origins in Beit Jala and of the political situation in Palestine. The first generation born in Chile is probably more aware than the second generation. However, my travels there and my writing about Palestine allowed us to reconnect and rethink our connection to the place and its politics. Many people from my generation in Chile are visiting Palestine and connecting with the land of their grandparents, and some are even learning the Arabic language.

How do Palestine and Chile influence your writings?

Chile, where I was born in 1970 and raised, where I went to school and university, and where I worked as a journalist until the age of 30, has always been very present in my writing, both in fiction and non-fiction texts. Chile is always a site and a political concern. Growing up under such a long and deadly dictatorship from 1973 until the 1990s, and living in a country turned upside down by neoliberalism, where the growth of inequality has been devastating to the country–all of this has been thematized in my writing.

In my recent essay, “Zona Ciega,” I discuss the violence that ensued during the 2019 Chilean uprising, and how the militarized police force tried disabling the citizenry by shooting at their eyes. I also reflect on how this has been the case elsewhere in all recent revolts and protests, including in Gaza–notably in how this practice of disabling has been used simply because it is supposedly less lethal and bears less of a political cost.

Palestine has been a more recent interest in my writing. I wrote a first piece, “Becoming Palestine,” right after my first trip there in 2012, but continued to reflect on it through non-fictional work in “Becoming Others” and “Faces in my face.” These are now all part of a book titled Palestina en Pedazos, which is being translated into English. I have also written a few shorter essays and short stories about Palestine which, as a place, as a nation, and as a culture, matter enormously to me and constitute an ongoing reflection regarding colonialism and capitalist extractivism today.

What is your concept of Palestine in terms of attachment and memory?

While writing all the texts mentioned above, I realized that remembrance was quite difficult, as so many stories have been lost. My father and aunts were either not told much or don’t remember much, and they only remember the happy stories and anecdotes. Still, the bits and pieces allowed me to make sense of what living in the diaspora had entailed for them. Some stories include how my grandparents met, how my grandmother was due to marry an older man from the family and to get rid of him, she told him that if he was so ugly in daylight, how would she tolerate being with him in the dark without screaming in fright? Anecdotes such as this, but none of the hardships. They were not born there and thus do not remember much of their parents’ stories. Besides, my family had departed to Chile long before the Nakba.

But after reconstructing the family memory, I was certainly more interested in the present day situation and compelled to take a political stance. For me this has meant reading the history of the place, studying the political problem, returning to visit, and writing about the most urgent political questions.

In what ways do you relate to Palestine, not having been born there? And how does this differ from the memory of your Palestinian family members who have tangible recollections of Palestine?

“What came out as a description of my trip was that I was returning…I realized there was some sort of family mandate to return, even if this was a place I’d never been before. “

Lina Meruane

I was not born there, and as I say in my writing, I never had recollections of my own, but rather a family rumor of sorts. However, over the last years I have begun building my own story, as I have been to Palestine twice and reflected so much about it. And I have a political investment in the situation of Palestinians in Palestine. When I write about Palestine today, it is a political decision, a decision not to keep silent.

How do you relate to the Palestinian right of return and what impact does this have on you and your writings?

What was striking to me was that, upon my first trip, what came out as a description of my trip was that I was returning. Unconsciously. The word “return” was present, so rather than say I am travelling to or visiting Palestine, this other word came up. I realized there was some sort of family mandate to return, even if this was a place I´d never been before.

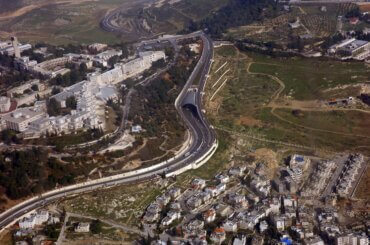

I later learned a lot about what this entails. For example, that under the British Mandate, Palestinians were not allowed to return to their homes. This was the case in my grandparents’ situation. After the creation of Israel in 1948, return was “legally” ruled out. Not only that, the homes of Palestinians were said to be “abandoned” and given to Israeli citizens and settlers, and entire Palestinian towns were destroyed. This has not changed. In fact, it has only become worse as more and more Palestinian homes and lands are appropriated by Israel, and more and more settlements are built in the Palestinian territories, in order to make it impossible for them to ever regain their lands.

But to answer your question, although my family there suffers from occupation, dispossession is not their immediate problem. Still, this being the problem of so many people in Palestine and in the vast Palestinian diaspora, dispossession feels like my problem too. And therefore I am compelled to remind people about it as often as I can.

Lina Meruane is an award-winning Chilean writer and scholar. She has published two collections of short stories and five novels into several languages. Meruane has written several non-fiction books, among which is her Palestinian memoir, published in Spanish as Volverse Palestina, later expanded and re-titled Palestina en Pedazos. The book was published in Arabic (Kotob Khan, Egypt) and is currently being translated into English. Meruane received the prestigious Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Novel Prize (Mexico 2012), the Anna Seghers Prize (Germany, 2011), the Chilean-Arab Prize (Chile, 2014), as well as grants from the Guggenheim Foundation (US), the National Endowment for the Arts (US) , and a DAAD Writer in Residence in Berlin, among others. She currently teaches Global Cultures and Creative Writing at New York University.

“My grandparents on my father’s side came to Chile as children, in the early nineteenth century.” — Did you mean early 20th?