Editor’s Note: The following article is based on the research paper “COVID-19 data analysis and modeling in Palestine” by Ines Abdeljaoued-Tej that was posted on the preprint service medRxiv on April 29, 2020.

Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky. There have been as many plagues as wars in history; yet always plagues and wars take people equally by surprise.

Albert Camus, The Plague

Albert Camus set his famous novel The Plague in Oran in Algeria under French colonization. He wrote it in 1947, two years after the large massacre in Sétif of Algerian civilians by French soldiers, in May 1945, and seven years before the start of the Algerian revolution, on November 1, 1954. Yet, as observed by Edward Said, “the Algerian setting [in Camus’ novel] seems fortuitous, unrelated to the serious moral problems it poses. True, Arabs die of plague in Oran but they are not named either, whereas Rieux and Tarrou are pushed very far forward in the action.”

Seventy-three years later, politicians around the world seem to have been taken aback by the new COVID-19 epidemic. Scientists have however warned for years about the inevitability of such an epidemic. Starting from the city of Wuhan in China in late December 2019, the pandemic quickly spread to the rest of the world along the main intercontinental air routes. At the time of writing this article, there are officially more than three million infections and more than 220,000 deaths. Statistics vary widely from country to country, revealing significant differences in anticipation and management of the crisis.

To echo the words of Edward Said mentioned above, we propose to examine the COVID-19 epidemic in Palestine through mathematical models, developed by Ines Abdeljaoued-Tej, one of the two authors of this article, which aim to determine the actual number of infected cases and to predict the course of the epidemic.

As of April 22, 2020, there are officially 466 COVID-19 infected cases in Palestine, including 318 cases in the West Bank, 131 cases in East Jerusalem and 17 cases in Gaza. Four people have died, including two in the West Bank and two in East Jerusalem. Using a mathematical model based on the number of reported infected cases, the number of deaths and the effect of the 18-day delay between infection and death, this study estimates the actual number of COVID-19 cases in Palestine as of April 22 between 506 and 2,026. [1] The study also analyzes the evolution of the epidemic in Palestine using population dynamics with two SEIR models (S for susceptible, E for exposed, I for infectious and R for recovered or deceased). The simulations predict a total number of infected cases of 11,014 in the most optimistic scenario and 113,171 in the most unfavorable outcome. The peak of the pandemic is expected between May 22 and May 27, 2020.

The COVID-19 morbidity rate in Palestine, that is, the ratio of the number of people infected to the total Palestinian population, is around 0.009%. The death rate representing the number of people who died from COVID-19 in Palestine is 0.6 per million people. The real indicator of the danger of the epidemic is the fatality rate, which represents the proportion of deaths compared to the total number of infected cases. The fatality rate for COVID-19 in Palestine is 6.7 per thousand people. It is much lower than the rates in neighboring countries. The number of infected cases (incidence) is 88.4 per million, which is also lower than most neighboring countries. It should be noted that these figures are temporary and incomplete. They were obtained on the basis of the tests carried out; note that the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has a sensitivity of 70%. [2] The number of deaths is recorded in hospitals and does not include deaths at home (therefore of cases not reported). But these figures remain an indicator in order to contain the outbreak and prepare for targeted deconfinement.

The “basic reproduction number R0” is equal to 1.54. Changes in transmission speed over time are recommended to bring it down the critical threshold of 1.

Population dynamics: from aristocracy to epidemics

The stochastic branching process (or Bienaymé-Galton-Watson process) is used to model epidemics at the population level. It was introduced in the 19th century to study the disappearance of the surnames of the British nobility: a noble reproduces with a rate called the “basic reproduction number (R0),” which becomes the average number of people infected by a sick person when applied to epidemics. If R0 <1, a patient infects on average less than one individual, and the disease disappears from the population over time. Conversely, if R0 > 1, the disease can spread in the population and become epidemic. This number therefore makes it possible to determine if the epidemic can spread in the population, at what speed (doubling time) and with what magnitude. Its calculation requires the use of more or less complex models.

Compartmental models were created in the 1930s by Kermack and McKendrick. The principle is to divide the population into epidemiological classes such as those susceptible to infection, those who are infectious, and those who have recovered and acquired immunity or are deceased. The state of the epidemic is determined by knowing the size of these three classes of population. At each point in time t, we can consider the number S(t) of susceptible people, the number I(t) of infected people, and the number R(t) of recovered (and therefore immune) or deceased people. Each of these quantities is a function of time t, which we cannot really measure at all times, but it is measured regularly at certain times (for example daily or hourly), and these measures provide both an abstract model of this function and a daily assessment of the epidemic.

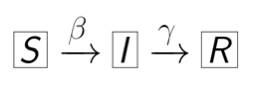

The functions S(t), I(t) and R(t) are linked to each other by laws that describe how they influence each other. For example, their sum S(t)+I(t)+R(t) represents the total population which therefore remains constant over time. The other laws which describe the evolution of the epidemic can be represented by the following diagram, known as the SIR model:

The number β represents the rate of transmission, i.e. the rate of susceptible people who become infected and the number γ represents the rate of recovery or death, i.e. the rate of infected people who recover and become immune or die.

Concretely, these laws which describe the evolution of the epidemic over time take the form of a system of differential equations whose solutions include the future values of these functions. Solving differential equations is difficult in general, both conceptually and technically. A difference equation (rather than a differential one), in which time is measured in discrete units, is simpler, but works the same way. [3] This is, moreover, the basis of the numerical method for solving differential equations on computers.

The system of differential equations above which represents the SIR model can be understood as follows. The derivatives d/dt give the variations of the functions S(t), I(t) and R(t) as a function of time t. The term S(t)I(t) represents the number of contacts between susceptible people and infected people. β being the transmission rate, there are therefore βS(t)I(t) newly infected people. These are subtracted from susceptible people, and add to infected people. Likewise, among those infected, some will recover or die. γ being the rate of recovery or death, there are γI(t) newly cured or deceased people who are removed from the infected population.

The SEIR model is a little more elaborate. It is obtained from the SIR model by adding a new epidemiological class to take into account the duration of incubation (via the incubation rate α), namely exposed people (infected non-infectious) who are therefore not contagious, represented by the function E(t). By taking again the diagram and the system of the SIR model, and by adding a term αE(t), one obtains:

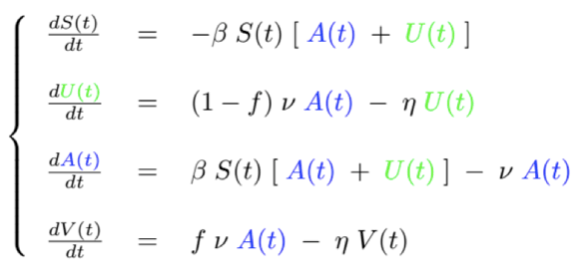

The study we are presenting is based on a refined SEIR model, tested at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in China and France [4], which takes into account three classes of infected populations represented by functions A(t), U(t) and V(t). Any of these infected populations can transmit the virus to susceptible people S(t). The first class, represented by the function A(t), is made up of people infected but who do not know it, called asymptomatic. The other infected people, called symptomatic, are divided into two classes represented by the functions U(t) and V(t). The function U(t) represents symptomatic people not listed by the public authorities. They are infected people with symptoms but who do not know they are carrying the virus. They are therefore not officially recognized as infected (either because the COVID-19 test turned out to be negative, or because they simply escaped the various checks put in place). The population of those who are symptomatic, infected and who tested positive for the virus are represented by the function V(t).

The infected people are thus divided into asymptomatic A(t) and symptomatic U(t) and V(t). Only those infected who have tested positive for the virus, represented by the function V(t), are known to the public authorities. These are the ones that appear in the daily reports of the epidemic. However, the three population classes A(t), U(t) and V(t) are carriers of a highly contagious infection. Draconian control is applied to class V(t) to avoid contact with class S(t) of healthy people who are likely to be infected. However, the latter can be infected by both class A(t) and class U(t), with a transmission rate β. In this refined model, there are therefore βS(t)(A(t)+U(t)) newly infected people. The model also takes into account the number of days n from which symptoms appear on carriers of the virus (estimated at 7 days for COVID-19[5]). After this period of n days, only the proportion f of asymptomatic people become symptomatic and test positive. They are added to the class V(t). The rest of the asymptomatic population, namely (1-f)A(t), escapes the mesh of control and is added to the class U(t). Every day, class A(t) therefore contributes to class V(t) by fA(t)/n people and to class U(t) by (1-f)A(t)/n people. Finally, part of the symptomatic U(t) and V(t) is removed after a certain number of days with a rate η. We obtain, by noting the inverse of n by ν:

The need to impose lockdown comes from the classes of infected but unreported, that is, A(t) and U(t). These two functions are not known at any given time. Their objective estimation and the study of their evolution are however necessary to understand the pandemic and to reduce their unintended damage (due to an absence of symptoms, or to the confusion of certain symptoms with less contagious diseases, or to unavailable or unreliable tests).

Figure 1. SEIR with f = 0.6, η = 1/7, n = 7, β = 4.55 10-6 et R0 = 1.54. We obtain an estimate of the maximum number of cases on May 22, 2020 with 8,095 reported cases and 2,919 unreported cases.

Palestinian resilience and Israeli threats

As of April 22, 2020, there were 466 infected cases and 4 deaths in Palestine for a total population of 5,077,760 inhabitants, which corresponds to a rate of 88.4 infections per million inhabitants (an incidence of 88.4 per million inhabitants). This rate places Palestine at a level comparable to Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq and Lebanon (between 2.4 for Syria and 99.2 for Lebanon per million inhabitants). These countries are doing much better than their neighbors: Israel, Turkey, Iran and Saudi Arabia (334.1 cases infected in Saudi Arabia and 1,610 in Israel per million inhabitants). Palestine is also doing very honorably in terms of the number of COVID-19 deaths with a rate of 0.6 deaths per million inhabitants, ahead of Jordan (0.7) and Lebanon (3). It is far ahead of Israel (21), Turkey (27) and Iran (63).

Figure 2. Number of deaths at t0 depending on the number of cases, with a delay of 18 days (t0-18 days). There are two groups of countries according to the importance of the number of deaths in these countries.

These results may be surprising given the conditions in which Palestinians under Israeli occupation live. Indeed, Israeli settlement and apartheid policies have prevented the development of basic services in Palestinian society and have therefore deprived Palestinians of their basic rights guaranteed by international humanitarian conventions, such as access to health and to education. During the first intifada, the Israeli army closed all Palestinian nurseries, schools and universities, making education illegal for four and a half years from 1988 to 1992. Palestinian civil society defied military orders by organizing education in secret. Palestinians are showing today the same resilience and civic awareness in the face of the COVID-19 epidemic.

One might legitimately think that the restrictions imposed by Israel on the Palestinians’ freedom of movement, through checkpoints and the annexation wall, would slow the spread of the epidemic. However, as soon as the virus arrived in the Palestinian Territories, the “benefits” of this perverse and illegal system under international law became blurred. The repressive and segregative characteristics of the system have proven to be the main obstacle to taking preventive actions against COVID-19 on the part of the Palestinian authorities.

- On March 26, 2020, the army confiscated poles and sheeting that were intended for the building of eight tents: two for a field clinic, four for emergency housing and two for makeshift mosques, for residents evacuated from their homes in the northern town of Khirbet Ibziq in Jordan Valley in the West Bank.

- At dawn on Friday, April 3, 2020, Israeli soldiers and police broke into the house of the Palestinian Authority’s Minister of Jerusalem, after blowing up the main doors, causing extensive damage and terrorizing his children. He was questioned briefly and asked about his activities on behalf of the Palestinian Authority concerning the fight against the coronavirus in East Jerusalem. During his arrest, he was forced to wear a dirty mask which had traces of dried blood.

- During the night of Tuesday, April 14, 2020, Israeli police raided a coronavirus testing clinic in the Palestinian neighborhood of Silwan in East Jerusalem and arrested its organizers because the clinic operated in collaboration with the Palestinian Authority. According to the director of the clinic, there is a shortage of tests for COVID-19 in Silwan where doctors say there are 40 confirmed cases and where living conditions due to overcrowding could lead to rapid spread of the virus. The tests were to be processed by the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the West Bank. However, Israel prohibits PA activity in Jerusalem.

- In March, Israel blocked PA workers from disinfecting public spaces in the city. The Israeli Ministry of Health opened a testing clinic in Silwan on April 13, 2020, but it is only accessible to members of the health management organization Clalit: most residents of the neighborhood are members of other organizations and cannot be tested there.

During the epidemic, Israel continued its violent routine of occupation throughout the West Bank. Between March 1 and April 3, 2020, its army arrested 2017 Palestinians, including 16 children. Israeli soldiers dumped a number of Palestinian prisoners and workers with COVID-19 symptoms at Israeli checkpoints without medical care or coordination with Palestinian health services. In addition, the Israeli government is not testing Palestinian workers from the West Bank for COVID-19 and is refusing the Palestinian Authority’s request to test workers returning to the West Bank. Nor does it monitor the housing and working conditions of the 20,000 Palestinian workers who sleep in Israel and hold jobs considered “essential”. According to Palestinian Authority figures, as of April 20, 2019, out of 319 carriers of the virus in the West Bank, 85 have been infected while working in Israel, and they in turn infected another 101.

The Israeli settler-colonialism and apartheid regime that the Palestinians have endured for decades has led to the fragmentation and de-development of the health system in Palestine. The Gaza Strip has only 87 ventilators for two million people, and the West Bank has 256 ventilators for three million people. But 80 to 90% of these ventilators are currently unavailable, according to Gerald Rockenschaub, head of the WHO mission in Palestine. “They are used by people who have suffered heart attacks, strokes and other incidents requiring intensive care,” he said. According to WHO, Gaza has 87 intensive care unit (ICU) beds and the West Bank has 213 ICU beds. But most of these beds are already occupied by patients with serious illnesses.

As of April 23, 2020, 26,000 samples have been tested for COVID-19 in Palestine, including 4,368 samples in Gaza. However, health authorities are continuing to appeal for support to procure additional lab testing kits. Most of the kits were provided by WHO and the Ministry of Health in Ramallah.

Gaza, ultima verba

With its two million inhabitants packed in a strip of 365 km2 (just under 40 km long by 10 km wide), Gaza is probably one of the most dangerous places in the world in case of spread of the COVID-19 epidemic. In a webinar organized by American Jewish Committee on April 24, 2020, Nickolay Mladenov, UN Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process, said:

Gaza is the second most populated place on the planet with probably the worst health system in the world. A health system that has been chronically underfunded and chronically under-supported for more than a decade. Can you imagine what would happen if the virus got to this small piece of land so densely populated and the level of damage it could cause? A lot of our focus over the past three weeks has been on putting in place basic prevention mechanisms inside Gaza to be able to make sure the virus does not spread. I must say that we have seen some really really smart people inside the Gaza Strip, particularly among the health services who have done a remarkable job. There are currently 10 or 12 people infected with the virus. The reason for their success is that the border with Israel is closed, no one can go-in or go-out. The border with Egypt remains the main entry point to Gaza. Large quarantine centers were established, and people from Egypt must spend not just two, but three weeks of quarantine in these centers before they can return home if they are not infected. In fact, a few days ago, someone in one of those quarantine centers escaped. He was arrested, his contacts traced and that is one of the reasons why his infection did not spread across the Gaza Strip.

Figure 3 : Layout showing the procedure to be followed for the reception of travelers returning to Gaza from Egypt.

Mladenov fails to mention that if the health system in Gaza is “the worst in the world” and if it has been “chronically underfunded and chronically under-supported” it is because of the three Israeli wars against this territory, in 2009, 2012, and 2014, and the inhuman blockade imposed by Israel and its Egyptian subordinate for more than 13 years. In March 2019, Dr. Tarek Loubani, Canadian-Palestinian emergency physician and associate professor at Western University in Ontario in Canada who has practiced regularly for the past few years at al-Shifa hospital in Gaza declared:

the health situation in Gaza is dire and it gets worse. Since the Great March of Return, what was a slowly developing disaster has become a manifest and present catastrophe. The blockade eliminated the ability of the health system to manage daily care needs long before the March started. Patients with chronic conditions such as kidney disease and diabetes were already suffering from a lack of appropriate equipment (dialysis machines, for example), and the drugs needed to manage their condition. Cancer patients were and remain completely subject to the whim of the Israeli security apparatus, which is accused of swapping cancer patients’ access to life-saving treatment for information and interrogation of these patients. Whether intentional or not, the blockade prevents essential drugs and medical equipment from entering Gaza. It prevents Palestinian health workers from traveling freely to train elsewhere and international health workers, like me, from traveling freely to provide care and training in Gaza. It also degrades, and eliminates, the essential infrastructure that any health system needs to survive, such as electricity or clean water.

In early April 2020, Israel linked any assistance it might offer for the Gaza Strip’s efforts against coronavirus to progress in its attempt to recover two Israeli soldiers lost during the 2014 war in the Palestinian enclave.

According to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), 75% of the inhabitants of Gaza are refugees whose ancestors were expelled from their cities and villages in Palestine following the ethnic cleansing that accompanied the creation of Israel in 1948, a year after the writing of The Plague by Albert Camus. Since then, wars and epidemics have “fallen on their heads” in the indifference of the international community which grants total impunity to those who maintain their ordeals; how long can they hold on?

Notes

- This study is not relevant to Gaza, where the epidemic has not yet spread.

- Fang, Y., Zhang, H., Xie, J., Lin, M., Ying, L., Pang, P., & Ji, W. (2020). “Sensitivity of chest CT for COVID-19: comparison to RT-PCR”, Radiology, 200432.

- For an introduction to differential equations see “Mathematics without apologies“, Chapter 4, “Applied stochastic analysis” by Michael Harris, Princeton University Press (2015).

- Zhihua Liu, Pierre Magal, Ousmane Seydi, and Glenn Webb. “Understanding Unreported Cases in the COVID-19 Epidemic Outbreak in Wuhan, China, and the Importance of Major Public Health Interventions”, Biology, 9(3):50, 2020.

- Flaxman, S., et al. “Report 13: Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries”, Imperial College London (2020), doi : https://doi.org/10.25561/77731.

I’m a bit sceptical about these predictions. This SEIR model predicts a peak of 8000 at the end of May, and before that a continuously faster increase in the number of reported cases per day. However the real numbers are different. The last 7 days (23-29 April) only 9 infections were reported, the 7 days before that 44 infections, and before that resp. 28, 130, 70, 20 , 12, 24, and before March 5 no reported infections. The big peak of 130 in early April is over, a smaller peak of 44 two weeks later has also passed.

The trend with multiple peaks suggests that new infections came not from organic growth of the number of infected people in Palestine, but from e.g. labourers returning from Israel.

In the graph the black data points should also not be compared to the calculated lines because the lines decrease after some time (due to recovery or death), but the data points don’t, they are the cumulative number of infected.

See the data here: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/state-of-palestine/