This piece follows up Emad Moussa’s account of entering Gaza from Egypt that we ran in July.

The journey through the turbulent Sinai was harsh and oftentimes degrading, but I finally made it into Gaza after fifteen years of absence. I wasn’t sure what to expect, especially as I arrived only 10 days after the last war had ended.

The journey from the border to Gaza City is roughly 35 minutes. The driver, however, took several detours so to avoid the areas where the Israeli airforce struck. The driver pointed out that the bomb craters were soon filled with sand and mud to allow cars to pass.

Since his taxi was his only source of living, he was super careful not to expose it to anything other than a smooth road. When I was last here, bumpy roads were the norm. We often joked about how the Gaza roads were better designed for Israeli tanks than they were for civilian vehicles.

It was good to know Gaza has now better roads and seemingly better infrastructure – thanks in part to Qatari money and other donor countries, or better financial management?

“Nothing fancy, they’re just renewed way too often because of the wars. We pave a road, they come and bomb it, then we pave again,” the driver commented as he coughed hard; it was Covid, I feared, and stuck my head out of the window.

As we approached Gaza City, the scenes of destruction became more visible.

Outside the Shuja’ya neighbourhood in Eastern Gaza, a bombed supermarket caught my eyes. Why? I asked the driver. “Because, apparently, they made rockets out of chocolate bars,” he replied as he laughed and coughed more.

Around the destroyed supermarket, almost every house suffered damage, some severely.

In Gaza، home insurance isn’t a thing, or at least almost no one pursues it. So, residents have to rely on International or local aids to help them rebuild or fix their homes, which for the vast majority of families is their only capital in life, and which they have worked most of their lives to obtain.

There are still families who are yet to receive help to rebuild their homes which Israel destroyed in the 2014 onslaught.

Family Reunion…in the time of Covid.

When I left Gaza 15 years ago, my parents had in mind the possibility of never seeing me again. Up until early this year, that possibility remained. The anxiety of taking a gamble and heading to Gaza after Egypt had opened the border in February wasn’t only about the risk of getting trapped there for months, but also about actually breaking what seemed to be a forced reality – not seeing my family again.

Having passed the compulsory social rituals, and the who-cares-there-is-a-pandemic handshakes, hugs and kisses, I was finally allowed to settle down and talk to everyone. When I say everyone, I mean the streams of cousins and other relatives who were little children when I left.

Apart from the sarcastic comments on the never-seen-before grey hair, everyone was extremely warm.

In the brief moments of silence – when the reservoir of curious questions by my relatives momentarily ran out – one can clearly hear the Israeli drones buzzing relentlessly in Gaza’s sky.

In the two weeks I stayed there, I don’t think there was a single day without the drone noise in the background. After a couple of days, it becomes routine and you stop hearing it. Nothing is characteristically more Gazan than becoming “drone-deaf.” (I tried to capture a video of a drone overhead here; though it looks like UFO footage.)

For my parents, time stopped the day I left Gaza. As soon as I arrived home, they acted as if I was never away, picking up what they left off at that point in time 15 years ago. Showing that I missed the UK got them offended sometimes.

Outside my nuclear family, some relatives, although happy to see me, couldn’t hide their jealousy that I had the choice to leave Gaza. While irritating, I couldn’t blame them. There’s an assumption bordering on the absurd, but for obvious reasons, that life outside Gaza is a paradise. They often got shocked whenever I told them stories about the hardships I experienced in the UK. Some suggested that I should come back and settle down in Gaza. While few truly cared, others just wanted me to be in the same boat as them, so they would feel good about their own lives. You can’t blame them; life in Gaza is very hard, sometimes hopeless.

Socially Stagnant

It didn’t take long to see that socially nothing much changed in Gaza. It felt as if I left a month ago.

Initially, I thought, family is family, the same dynamics, the same atmosphere, why would they change anyway? But as I wandered around, it struck me that Gaza as a whole entered what seemed to be a time bubble.

You may expect a degree of social stagnation in a traditional, conservative society. But, it seems, the social reality has been more influenced by the skewed socio-political situation than it has by the society’s structure.

When I last was here, at the very beginning of the siege, society showed signs of non-conformist thinking developing. Even though the Second Intifada slowed down that trend, the elements of less conservative, less traditionalist social norms were nevertheless visible.

Today, as the situation deteriorated economically and politically, social conservatism seems to have taken a grip. For the older generation, of whom most of the leadership is composed, it’s a convenient environment.

For the younger, more educated generation, it’s stifling but accepted reluctantly in order to protect the collective against what’s viewed as external existential threats.

Debris and Memories

Unlike the three previous wars, the May war – albeit shorter – eliminated many of my childhood and teenage years’ memories. It was more personal than the others.

This time, Israel stepped up its aggressiveness by attacking the heart of Gaza City, a place that often escaped the intense bombing.

The most visible victim is al-Shurouq tower on Omar al-Mukhtar St. in Gaza’s commercial centre, one of the first high-rises to be built in Gaza following the Oslo process. (Here is a video of driving down the street past the rubble.)

It’s where I first learned how to use the internet, it’s where I worked briefly, and where I met with friends and, on occasions, it was the centre of some of my romantic adventures. Now, it’s become the largest pile of rubble I’ve ever seen.

But, who am I to lament sheer memories when there are hundreds of others who lost their lives, homes, and businesses in that tower? Incomparable.

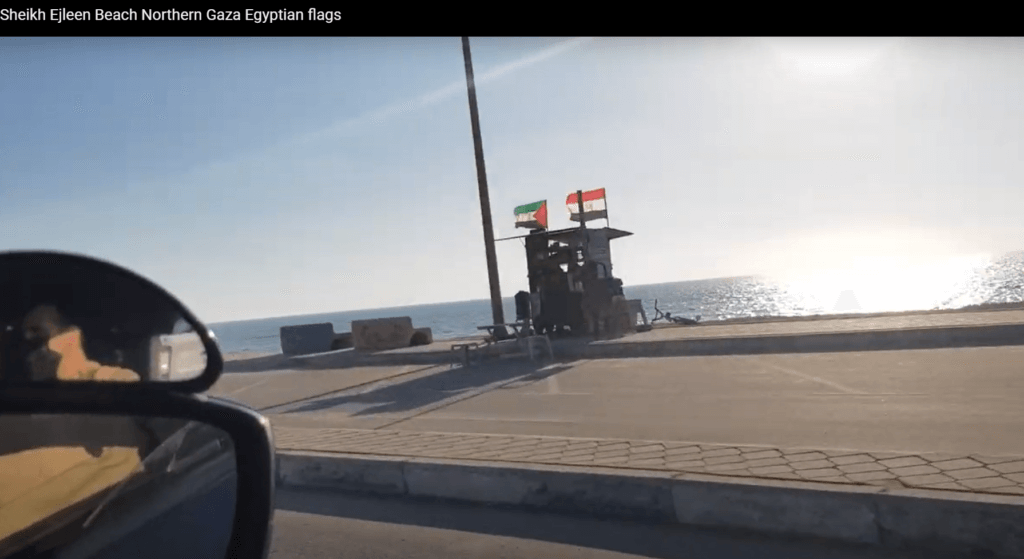

Egypt in Gaza

On top of the pile of what used to be al-Shurouq Tower sat a digger with an Egyptian flag attached to it.

“It’s part of the Egyptian reconstruction teams sent into the Strip last week,” my cousin, who drove me around, commented.

Egyptian workers were visible in almost every major site helping with the debris clearance.

While Palestinians welcome them with open hands, many, if not most, are skeptical about the true motives of Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. He’s not particularly liked by Palestinians, and Gazans in particular.

I heard over and again, if Egypt simply opens its side of the border freely with Gaza, then Palestinians will only deal with Egypt and Israel’s siege will become meaningless.

Others disagree, saying that Israel’s ultimate wish is to throw Gaza in Egypt’s lap and resolve its responsibility for the Strip’s 2 million residents. The Egyptians are aware of this scheme and tread carefully, some speculated.

The Egyptians don’t want to emphasise a divided Palestine, a Gaza and West Bank entities. “That’s exactly what Israel wants,” the restaurant manager told us as he checked whether we liked his shawarma wraps.

And yes, in Gaza, everyone has a strong opinion on the Egyptian question, so try not to argue too much. Some, in fact, were very suspicious possibly bordering on paranoid, saying that the Egyptian construction workers included among them Egyptian intelligence officers whose mission was finding the locations of Hamas’ tunnels.

“Egypt wouldn’t have interfered quickly and with such a capacity if Hamas hadn’t kicked Israel’s butt and nearly toppled the geo-political balance in the region,” the guy at the next table interjected.

As we drove on al-Jala’a street, one of Gaza City’s main roads, I was surprised to see a large billboard portraying el-Sisi with the phrase, “Palestine is a central cause for Egypt.”

El-Sisi in Gaza, imagine that! “They probably forgot to show us his middle finger, that’s probably this dude’s true intentions toward Palestine,” my cousin commented.

Poverty is Everywhere

Beyond the scenes of destruction, there’s the permanent state of economic deterioration. According to recent official figures, more than half the population in the Gaza Strip live in poverty.

The first thing one notices is the increase in the numbers of beggars. Second, is the almost endless stream of peddlers – some are children and university graduates – roaming the streets from early morning till late at night to sell their low-priced products, mostly veggies, fruits, and cold drinks.

I forgot how noisy they can be!

If the economic deterioration had a face, it would be that of the elderly man I met near Al-Azhar University in Gaza City. He was probably in his eighties, taking shelter under a small tree and selling rosaries, one Shekel for each.

A man of this age in Gaza would ordinarily be revered, dignified, and looked after by his children and grandchildren, and even close neighbors. Having to sell rosaries to survive signals the depth of Gaza’s desperation. I don’t know his circumstances, but I know this is something I never saw in Gaza before.

In the “Unknown Soldier” area in Remal neighbourhood, near al-Shurouq Tower, you’d be constantly approached by children selling tea and coffee. This commerce always existed, but their numbers seem to have increased ten-fold. (Here’s a video of the area on a Friday night.)

Those kids looked shabby, burdened with life problems much larger than their tender age. Some, in fact, were so desperate to sell, they were extremely rude.

For example, having refused to buy tea (already had some), the 12-something-year-old boy became very angry, then came close to my friend and coughed in his face. He apparently wanted to give us Covid-19, his way of settling scores. I didn’t know whether to laugh or unleash the dormant Gazan Hulk out on him.

On my family’s street, possibly two-thirds of my neighbours are now unemployed.

It was surprising to see that one of the neighbours who was once well-off is now a taxi driver renting someone else’s car. His brother, once a loaded construction contractor in Israel, now spends all his time sitting outside his house watching people pass by. It doesn’t help when many of those people whom he watched, also jobless, took watching as a profession themselves.

Resentment and Anger

In contrast, some of those affiliated with Hamas seem to have struck gold, forming a new class of beneficiaries.

While many praised Hamas’ administrative handling of Gaza (I certainly found it better than that of the Palestinian Authority), most, if not all, complained about corruption and monopoly. It seems that the very plague that Hamas had always criticised the Fatah-led Palestinian Authority for has now become Hamas’ own.

“They give the aid to their own people,” the shopkeeper told me.

“Do you need aid?” asked another person who was with us in the shop.

“Well, not necessarily,” replied the shopkeeper.

“Then you’re not being fair, you don’t know who gets what,” the second person hit back.

The cashier mumbled unintelligibly as he looked for some change and repeated his point: “I don’t think you know the half of it.”

In the taxi, the argument started all over again. “I don’t understand this, why are they so allured by money and power (referring to Hamas and Fatah),” the driver commented when he learned I was absent from Gaza for 15 years.

“You know what?” he went on. “It’s sadly hilarious…no, tragic actually. Both Hamas and Fatah are arguing over nothing. What power and resources does Palestine have, huh?”

“It’s like two idiots on a motorbike fighting over who should sit by the window,” he got louder. “Motorbikes don’t have windows, for God’s sakes!!!”

Praise the Resistance

But despite all of that, Gazans didn’t shy away from showing their exhilaration and pride over the resistance’s performance in the 11-day war in May. It didn’t matter what one’s political affiliation was, all praised Hamas’ military wing and other armed groups.

On my first day in Gaza, my uncle – a former political prisoner in Israel, and a known cynic and pessimist and someone who had little faith in the current resistance trend – said to me “The performance of the resistance in the last round was impressive.”

“Despite the fear and destruction, we all felt extremely proud and uplifted…God bless those heroes,” he commented enthusiastically.

Everyone in the room nodded in agreement.

Almost everywhere you hear it: “a lot of destruction, a lot of pain, but we truly taught them a lesson this time.”

This spirit is evident in the change of the political narrative all around Gaza, from the always-victim to the victim-fighter.

The walls used to be an open museum exhibiting portraits of martyrs, victims of Israel’s aggression. Today, this is supplemented with an emphasis on heroism. On the main roundabouts, billboards depicting the resistance leaders and others showing Hamas’ rockets units in action are the norm now.

At the end of the al-Jala’a street, there’s now a monument showing a Qassam M75 Rocket, a home-made rocket used to hit Tel Aviv for the first time in the history of the conflict.

Against the backdrop of fifteen years of siege, four wars, deprivation, and continuous aggression, any form of achievement is seen as a victory. But sometimes it’s over the top.

In my first week in Gaza, five Israeli quadcopter drones were spotted in the sky over Gaza City. I took my younger brother and went up on the roof to see what’s happening.

It was so reminiscent, rather disturbingly, of the old times when my cousins and I used to sit on top of our house sipping tea and watch Israeli Apache helicopters as they launched their Hellfire missiles at police stations and other governmental buildings.

Long gone are the days when the bombing was somewhat targeted, and the so-called collateral damage wasn’t the norm.

From the rooftop, we could see two drones, fully lit. “Flickering lights, huh? Just jerking around for the sake of it. Not exactly a covert recon operation,” my brother said.

The local radio pleaded with the people, on behalf of the resistance’s “joint room of operation,” to ignore them.

Judging by the barrage of bullets we saw fired in the sky, we assumed some people didn’t listen and decided to shoot the drones down.

My brother and I had to take cover; stories of bullets landing and killing people weren’t unknown in Gaza. I always thought that as defiant Gaza is, it is equally reckless.

But sure enough, two of the five drones were reportedly downed and obtained by the resistance.

My pessimist uncle soon joined us. “I wouldn’t be surprised if the resistance reverse-engineer that Israeli technology,” he said. “Hopefully, next time we will give some more taste of their own doing.”

“You speak like Abu Obaida (Hamas’ masked spokesman),” I jokingly replied.

“You’re damn right I do. We’re in this shit together, Hamas or anybody else!” My uncle grunted.

As soon as the sky was clear of the drones, my uncle and brother went to check on their birds which they kept on the roof– pigeons, but they also have finches and parrot-like little birds – budgies I think, maybe you can tell me.

The banality of the situation was both funny and disturbing – I almost forgot what it felt like being able to simultaneously lead a normal yet not very normal life.

I nearly forgot how we used to watch Israeli airstrikes, and yet as that happened, discussed football and talked about girls. If it’s not normal, we make it so, or pretend it is. Life must go on, and in Gaza, even with its arms twisted behind its back.

Leaving…

Leaving wasn’t easy, I had to register my name with the Ministry of Interior upon arrival specifying when I wanted to leave roughly. Realising I couldn’t leave on time and had to wait for two more weeks or more for my name to come up, I decided to use a service called Tanseeq “coordination”. It involves paying the Egyptians a few hundred dollars – up to a thousand – for having the privilege of travelling on a certain day of your choosing and get to be treated with a semblance of dignity. I practically paid to simply leave and be treated like a human being.

As much as I was relieved I didn’t end up stuck in Gaza, I was feeling guilty to leave. I was haunted by a lot of questions, thinking about the people in that unique piece of land; about the broken dreams, the hundreds of bereaved families and orphaned children, the murky future, and the unbearable impoverishment.

But above all, I couldn’t shake off the selfish question, when will I see my family again? Will I ever?

Emad Moussa

Emad Moussa is a Palestinian-British researcher, whose focus is the social psychology of mainly the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.