I wanted the small rose tattoo because I saw Israelis with tattoos and I thought they looked cool. So I got it in 1988 when I was 18, a year after I had gone to Israel for the first time, on an eight-week summer high school program.

I grew up in the U.S. hearing the Jewish lore that says Jews with tattoos can’t be buried in Jewish cemeteries. But once I saw secular Israelis with their cool ink-stained arms walking the streets of Tel-Aviv, I decided I wanted one, too. I chose a small, dime-sized rose tattoo near my hip. I didn’t want a stem despite the tattoo artist’s suggestion to add some green color to the red flower. As a result, the rose has always looked suspended and groundless (and now quite faded), despite the permanent ink that permeated the skin decades ago.

I was named for my great-grandmother, Rose, a woman who left Ukraine in 1905 for a better life in the U.S. But I wasn’t thinking of her when I got the tattoo. Instead, I was thinking of my Hebrew (and middle) name, Shoshanna, which also means Rose, and which I believed connected me more deeply to secular Israelis as well as to the land and language of the Israel I was already in love with.

I didn’t care about my history in the country my ancestors called “Russia Ukraine” because Zionism got in the way. I was far more interested in what was happening to the east of Europe, in Israel. From a very early age–and with enormous help from the Zionist lobby’s efforts to create a brilliant branding campaign–I fantasized about and idealized this faraway land far more than I ever wondered about the true place my family was from. Instead of learning about Russia Ukraine, I dreamt of working in a field picking tomatoes on a kibbutz in Israel, singing songs while tilling the land, and putting down new roots with other young Jews who, like me, had cut the branches from their families in the U.S. (and Europe) and left their old lives behind. It was an ingenious fantasy because it allowed me to feel both grounded and rootless at once–tapping into my ancient history with a fresh start–a convenient contradiction.

Recently, however, I’ve been reading about my family that comes from Russia Ukraine. My father’s aunt, my great-aunt Esther, wrote 35 pages of the history she remembered before she died in 1993. When she wrote it, I wasn’t interested. I had recently–it felt more like finally–moved to Israel to realize my lifelong dream of living there. I didn’t pick tomatoes on a kibbutz, though. Instead, I went to graduate school in Jerusalem to study literature–a forward-thinking-enough decision that allowed me to both flee my family while also getting their approval (which apparently I still wanted) for doing something that had an academic goal (“My daughter isn’t wasting her life frolicking around in another country,” I imagined my mother saying to her friends. “She’s getting an actual Master’s degree in the Holy Land!”)

The fantasy I had developed about Israel served two purposes. First, believing in the Zionist dream, the nationalistic notion that Israel was righteous and just, worth defending and fighting for, satisfied my liberal political inclinations; this delusion grounded me as it filled an emotional need I had to feel selfless about large causes. Second, daydreaming about it gave me meaning, a feeling of superiority over the mundane everyday existence of teenage angst in the U.S. “If I could just get back to Israel, everything will be OK,” my Jewish teenage friends and I said to each other, depressed and anxious, once we had returned from the eight-week trip we attended when we were 16. We didn’t talk about what exactly would be “OK,” or why we felt this way, or even what we would actually do once we returned to Israel, how we’d make a living, grow a career, pay taxes (as it turned out, my going as a grad student conveniently allowed me not to have to deal with those things; I got by on a student visa).

If we didn’t get back there, we’d be OK, too. We were upper middle-class Jews living in the suburbs of major U.S. cities. We’d get jobs and buy cars and property and get fat and be fine. Yet we would continue to desire the Israel in our imagination like a faraway unrequited lover. This longing gave us purpose. We felt rooted thinking about Israel while we maintained a rootlessness in the U.S.

The Zionist lobby created the conditions so that we saw the Israel they wanted us to see, and these images were burned in our hearts: driving through the Judean Hills from inside an air conditioned bus; hiking up Masada; floating in the Dead Sea; sipping tea in a Bedouin tent; visiting museums of our ancient history and getting drunk in discotheques; flirting with Israeli soldiers we thought were hot; the smells of sumac and cumin wafting through the alleyways of the shuk (while our sexuality wafted and permeated everything we did); the rose-gold light that hits Jerusalem’s stone in the early morning and again in the late afternoon; the sunset on the blue sea. “My God, My God, May these things never end,” we sang in Hebrew, swaying and crying and holding each other to Hannah Senesh’s song, believing it was up to us to make sure these things never did end.

Like a love affair that takes place outside the mundanity of one’s everyday life, just out of reach enough to pine for it, so too was Israel outside of us enough to intoxicate us and make us long for it while also feeling close. The contradiction made us feel clear headed while also clouding us with love. For me, this ideal state remained conveniently unrealized.

I could have realized the dream. I could have made aliyah, as was my birthright to do, but I never did. I’d like to think somewhere in the back of my mind I knew that the land was Palestinian, that I knew I had no right to claim it as mine, but who knows, really. Once I earned my degree, I returned to Chicago in 1996.

Removing oneself and separating from Zionism, as from any ideology, can be difficult. The political and the personal–the two essential elements that make Zionism work–are deeply intertwined. It’s a duality, a nostalgic colonialism, and it seeps into the Zionist, making it hard to untangle. Undoing Zionism requires an uprooting, a deeply unsettling paradigm shift that can make you feel groundless. It requires more than just the realization that one’s family is from Russia Ukraine and not from Israel. It requires the painful undoing of a myth. But one of the rarely acknowledged harms of myths is that it’s not merely that they are untrue, it’s that they are all-consuming. Myths blot out other narratives, other aspects of our own identity.

Lack of interest in my family’s Eastern European roots also manifested when it came to food. My Baubi made beet borscht, brisket, tzimmes, rugelach, and homemade gefilte fish and tried, and mostly failed, to teach me how to make these, too. When I moved to Israel in the 1990s, I learned to make foods closer to my heart like hummus (“The national food of Israel!” I was told) and baba ganoush and falafel. The Jews I knew in the U.S. used a blender to make hummus; in Israel, we crushed the chickpeas and garlic by hand. Later, I spent time with Palestinians in their homes in the West Bank and listened to their stories of expulsion from their Palestine as we ate their hummus and baba ganoush and falafel. Palestinian homes dotted the hilly landscape.

When I was young, my thinking was dichotomous. My Israeli “history” matters, my Eastern European history doesn’t. For some reason, my parents didn’t carry this tension, perhaps because they were older, chronologically closer to their European roots than I was, closer to the Holocaust than I was. Room existed for them to be Zionists while also caring about their European history. They supported my love of Israel, and were confused and hurt when I undid my Zionism. Another problem for the Jew who separates from Zionism is that your family won’t understand you, may not like you, perhaps may hate you. They might think you don’t care about history even though you do.

“My Dad left Russia Ukraine in 1905, came by steerage to Ellis Island on the Hamburg Line,” my great-aunt Esther wrote in her account of my great-grandfather, Benjamin. She crossed something out where she wrote that her dad had “left.” Looking closer, I saw she had originally written, “escaped from,” instead of “left.” The original sentence actually reads, “My Dad escaped from left Russia in 1905, came by steerage on the Hamburg Line.” To leave rather than to escape. I don’t know why my great-aunt Esther changed her sentence, but she must have wanted to believe her parents had agency over their choice to leave their Russia Ukraine so that they didn’t sound helpless or weak.

My great-great uncle was a dressmaker in Odessa, my great-aunt Esther wrote. He had a small shop “down near the Black Sea of Russia Ukraine.” My great-grandmother Rose (great-aunt Esther’s mother) worked for her uncle, “sewing for hours by candlelight near the Black Sea.”

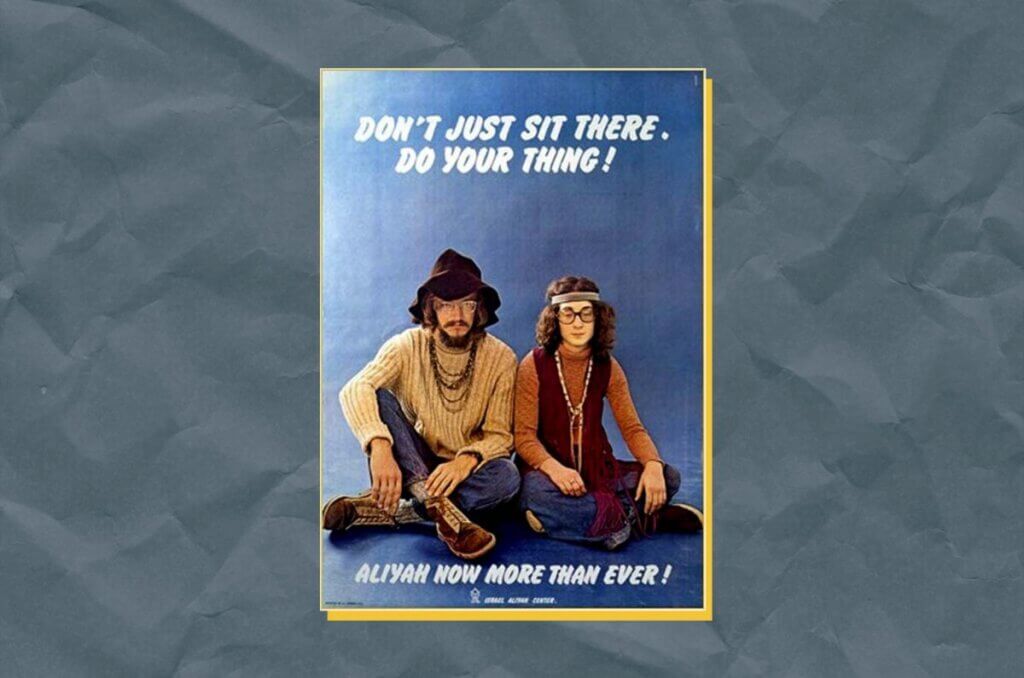

I longed for the Mediterranean Sea, not the Black Sea. Instead of tracing my family back three generations to Russia Ukraine, I could, as a Zionist, draw a straight line from me to thousands of years earlier to my homeland. “Your soul is here,” the posters at the youth aliyah desk in Chicago boasted, “Bring your body over.” On one poster, a woman sits alone on a beach, content, reflecting, at peace. She wears a simple one-piece black bathing suit and a big beige sun hat, looking out calmly at the teal blue Mediterranean sea. She’s got no physical luggage, no emotional baggage. She looks as light and breezy as the sea.

It’s easy to believe a mythical place is your home when messages all around you tell you so. The synagogues my family attended were Zionist. At Hebrew school, we drew maps of Israel and sang songs longing for the land, praying that “these things never end.”

At the overnight Jewish, Zionist, Socialist summer camp I attended, we created huge maps of Israel with ice cream, licking our fingers and flirting with each other as the ice cream melted in our hands; Jerusalem, Tel-Aviv, and Haifa literally beneath us at our fingertips. We were giant colonizer teenagers pretending to be hippies living in a collective, standing over the body of land, digging our hands into her. Green pistachio and mint ice cream were the forests–ethnically cleansed Palestinian villages, I’d learn later–butterscotch the desert, sprinkles and M&Ms the flowers, smurf blue the sea. The word Palestine never came up, for it did not exist in our hearts or in the histories we read. We Israeli-danced outside on the basketball court, lived in Israeli tents, worked in the mornings and spoke Hebrew, fantasizing about moving to our homeland. It’s OK to pick tomatoes in a field when you’re 18 if it’s in Israel, we told each other. Doing that in any other country would simply be wanderlust.

When I arrived in Israel at age 16 in 1987 for the eight-week summer program and set foot on the land, finally, for the first time, I felt I had consummated the unrequited wandering of the diaspora. Everything before that trip was Zionist foreplay, like hearing my family talk about Russia Ukraine and attending a simulated kibbutz camp in Michigan. The anticipation built for years. Arriving was the ultimate fulfillment. My soul was there, as the posters showed me. I had brought my body over. Like the woman in the poster, I, too, could sit alone on the beach content, reflecting, at peace in a simple one-piece black bathing suit and a big beige sun hat, looking out calmly at the teal blue (smurf blue) Mediterranean sea. I, too, could have no physical luggage, no emotional baggage. I, too, could look as light and breezy as the sea.

Ironically, as someone who had ignored her European roots, I always marveled on all my trips to Israel at how “European” it felt. This was the plan, of course, the brilliant Zionist branding, to create a white, European colonial political project in the middle of the Middle East, where someone like me could shed her old world Jewish European roots in a very European kind of way.

Looking back now, I think my decision to get that small rose tattoo, while seemingly couched in the desire to align myself with Israel’s secular society, was actually an unconscious effort to remain connected to my great-grandmother Rose after all, to my family who came from, and then escaped, Russia Ukraine. It turns out that the straight line Zionism led me to believe I could draw from Chicago to Israel wasn’t a straight line at all. It’s zig-zagged and broken and has hurt so many people.

And it’s left me at times reeling in its contradictions, carrying both luggage and baggage, not at all light or breezy, and feeling, even now, like a child who understands they’ve been lied to by an adult but has no language to express the pain.

***

Above all else, Zionism has been a catastrophe for Palestinians. It has resulted in generational trauma, expulsion, and displacement. And Zionism has been harmful to Jews in a very different way, in an erosion-of-the-soul-kind of way. Like racism and colonialism–for Zionism is these things–it damages both victim and perpetrator.

It’s unfortunate that my childhood Zionism taught me to be prone to nostalgia, to sentimentalize and to long for things out of my reach. Zionism, an ideology that gave my life purpose and meaning at a young age, inflicts an enormous amount of pain and suffering onto others. Most of all, Zionism is designed to obscure a colonial and violent past.

Even now, though I’ve separated from Zionism, I’m still prone to nostalgia. It’s creeped up on me again today while reading my great aunt-Esther’s history of my family.

I’m curious if my great-grandfather Benjamin mourned when he “escaped from” his home. He was born in Katrinislav, a city in South-central Ukraine. Katrinislav was renamed Dnipropetrovsk in 1926, and shortened to Dnipro in 2013. I wonder, once he left with his wife, my great-grandmother Rose, if he longed for the views of the Black Sea, the quarries and the bedrock, the mountains and the hills, the fields, birch trees, woods, the river that runs through Dnipro, all the streets he walked in his “Russia Ukraine.”

“He told me of the times he didn’t have enough warm clothes or shoes for the rough winter snows, as he ran the errands for his mother,” my great-aunt Esther wrote of her father. “But I remember how he often spoke of how sweet and delicious was a ripe red apple off a Russia Ukraine tree.”

Or maybe my great-grandfather wasn’t prone to nostalgia like I am, and didn’t have time to long for his own country, to ponder rootlessness and sentimentality and myth. Instead, he grabbed the red apple from a very rooted tree, I am sure, as he walked the streets of his Russia Ukraine, preparing to escape so that his daughter Esther might one day from the U.S. write that he had only left.

reply to Jon S: “Herzl and Jabotinsky -and other Zionist leaders- repeatedly expressed the desire to live in peaceful coexistence with the local Arab population and not displace it.”

SO WHAT? Putin said he was invading Ukraine to rid it of Nazis, not to occupy and annex it. The Japanese government of WW2 said it was seizing/invading all the countries of Asia in order to build a “Co-Prosperity Sphere”. Etc. Etc. The public statements of powerful, imperial agents are not to be accepted, even in their own moment, as unquestionably true. (As you apparently do) Even the project of the well-meaning and profoundly fair William Penn who made peaceful co-existence with the indigenous American tribes a working reality during his lifetime was undone by the greed and corruption of his sons in the Walking Purchase.

You rely on the words, perhaps honest and heartfelt at the time, perhaps not, of long dead colonists to legitimate the state of Zionism today. THIS.WILL.NOT. WORK. There are any number of reasons why your apologia is futile but perhaps the most relevant is that the moral zeitgeist of the moment is not with Zionism: It has turned against it.

Even if we were to acknowledge every single justification you and your fellow Zionists could muster, no matter how preposterous, in Israel’s defense that would still not serve to convince us that Zionism has a legitimate, moral, god-given right to massacre the people of Gaza with regularity (mowing the lawn), or deny the Palestinians the same basic human rights it protects so aggressively for Israelis, or attempt to re-write the American Constitution so that the act of boycotting Zionism/Israel in solidarity with the Palestinian people either does not exist or is unlawful.

Zionists chose to colonize Palestine. It would be, IMO, an act of rabid antisemitism to not inform them, in every way imaginable, that the world is not with them in their project. Zionism’s re-writing of history, perpetrating injustice, justifying racism and Islamophobie, seizing land, destroying homes and engaging in routine violence against the indigenous Palestinians will never, repeat, never serve to win it the allies it thinks it so richly deserves.

I think Zionists know all this and further, I think their willful refusal to accept it for the reality it represents explains the near-universal delusionism that marks Zionist culture and discourse.

Looking forward to hearing you explain how wrong I am.

Palestine History – Alan Hart with Ilan Pappe

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1VBjdxzjuyE

Reply to JonS: I misunderstood nothing. You chose to posit that because Herzl and Jabotinsky allegedly wrote/said something about peaceful coexistence with the indigenous Palestinians that that somehow exonerates/elevates/angelizes Zionism. It does not. Your words:

Zionism at its founding was justified and even heroic .But the Zionists achieved their primary goal 50 years after the movement’s founding. The state was established, mass immigration absorbed, the economy stabilized, most external threats defeated or neutralized. Now, in 2022, Zionism has become an anachronism, as an ideology and as an organization. What we need now is to find a way to end the occupation and terrorism and achieve peace with the Palestinians.

Let’s see if I misunderstand you now: So, 70-odd years after achieving their primary goal, absorbing millions of immigrants, stabilizing the economy, neutralizing all external threats, etc., we Zionists (now) believe our founding ideology is out of date and not suited for purpose (now) so we would really appreciate it if you Palestinians would be so kind as to forget/forgive/forego/forever any memory of the things we Zionists did (and do) to you Palestinians to get to this point in our history, so we Zionists can live in peace.

JonS did I recapitulate your comments correctly or do I still misunderstand you? Please elaborate.

Modest Proposal: if, you Zionists (post;fusion;Labor;synthetic;practical;political, etc., etc. truly want to end the occupation its simple: Have the Israeli government announce a date fixed for withdrawal and pull all the Settlers and their baggage out of the Occupied Territories. SO simple, right? Israel has lots of experience withdrawing from occupied territories. See Lebanon. See Gaza. See Sinai.

And I am not sure if you are chiding me for using the term “mowing the lawn”: Are you?

One more note: do you realize how offensive it is to refer to the killing of people in Gaza as “mowing the lawn”? Those are real live people , not grass.

If yes, I suggest you learn the origins of the term (will it surprise you to learn of its Zionist origins?) I was quoting the term not using it:

“New York Times asserted [it] was the “operative metaphor” most widely used in Israel to describe the Gaza operation.”

I have hundreds of friends and comrades in Gaza. How many do you have?

Do you realize how offensive it is to hide behind feigned concern?

First I want to say that this is very well-written and heartfelt. I am not going to make fun of it.

I do want to posit a theory as to why most American Jews from Eastern Europe chose to forget their Eastern European roots. The primary reason in my opinion is that the history of Jews in Eastern Europe is one of persecution and fear. Church anti-semitism reinforced with ethnic blood and soil nationalism created an atmosphere where the Jews were foreigners in the places they were born. They were from there but they were not of there. It wasn’t their country and they were made aware of that on a regular basis. They certainly had a unique culture which was theirs but it was not Polish, or Russian or Ukrainian. When they escaped from there (and yes, escaped is the proper term) they took their own customs with them but without any tie to the greater context of the countries in which they lived. Certainly initially they were still connected to the specific places they were from and more so to the people that they left behind. After WW2 the specific milieu they came from and the people they left behind were all gone. There was nothing tying them back to Eastern Europe except for the family customs they brought with them and that they were gradually forgetting. Their history back in the places they came from was dead and gone along with the social, cultural and religious institutions that might have maintained it. If anything the places and history and Europe in general became associated with persecution and death, fully cutting any sentimental ties that might have existed.

But they were still Jews. So when Zionism proposed creating a bond and filling that hole of historic memory with something exotic and new while providing a link to a more ancient history the audience was ready for it.

And also, yes, life in America is pretty boring overall and generally very individualistic so people look for something greater than themselves to focus their passion on. Zionism offers that as well. More so in the earlier years when the survival of Israel was at risk. That’s actually likely one of the reasons why Israel has become less important to American Jews. It no longer offers any sense of compelling urgency that would drive people to care about it as an ideological project that gives someone a feeling of personal mission as part of a larger whole. It became too rich and powerful.