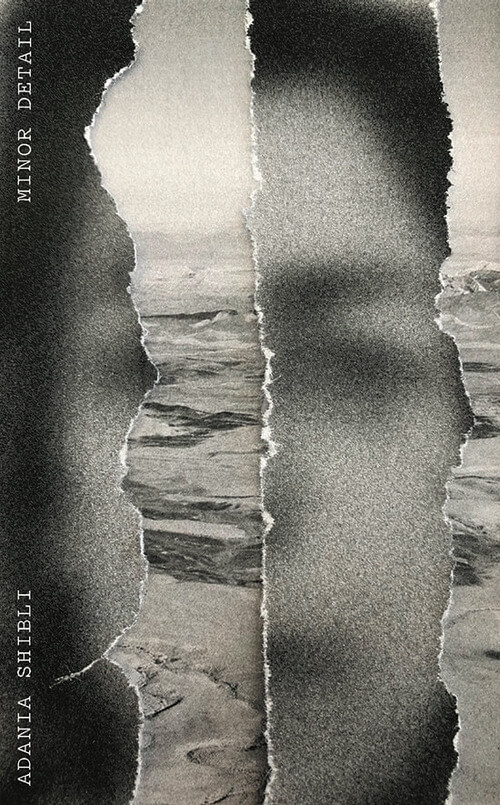

MINOR DETAIL

by Adania Shibli

Translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

144 pp. New Directions Publishing, $15.95

Much has already been written about Minor Detail, the philosophical novel penned by Palestinian author Adania Shibli, published in Arabic in 2016, and much more will be said now and in years to come. Elisabeth Jaquette’s remarkable translation released in 2020 by New Directions has been well received — longlisted for the 2021 International Booker Prize and named as a finalist for the National Book Award in translation.

The plot of this spare, haunting novel is loosely based on a real-life war crime that an Israeli officer and his men committed in August of 1949. In 2003, Ha’aretz published an account of the unit’s rape and murder of a Bedouin girl whose body they buried in the Negev desert. This is one of the rare Israeli war crimes whose perpetrators have been prosecuted and punished. From this tragic historical seed Shibli develops a two-part diptych that fictionalizes the events leading up to the crime as well as its reverberations and echoes decades later.

Part 1 of Minor Detail recounts the activities of a nameless Israeli officer whose unit is charged with the ethnic cleansing of the Negev region during the founding days of the nascent Israeli state. His orders are to eradicate Arabs and so-called “infiltrators” [1] along the armistice lines with Egypt.

Shibli delivers this portion of the novel using a third person objective narrator that meticulously relays the officer’s actions in a taut literary style devoid of emotion or personality. The section consists of a detached yet strangely hypnotic recitation of the officer’s bleakly regimented daily activities — his bathing habits, his eventless reconnaissance tours of the desert landscape, his arid interactions with his men, his bizarrely disinterested treatment of a debilitating spider bite on his leg that worsens to the point of putrefaction.

The infected spider bite — and the way he eventually blames its stench on the kidnapped girl — become one of the minor details that accumulate to form a tableau of the sociopathy required to rape, massacre, and subjugate another people with impunity.

Part 2 of the novella picks up the thread of the story in an entirely different voice and style decades later in occupied Ramallah. The first-person narrator in this section is an eccentric, anxiety-ridden Palestinian woman who reads about the 1949 war crime in the newspaper. The incident catches her attention due to a salient detail: the rape and murder had been perpetrated on the date of her own birthday, twenty-five years before she was born.

As the narrator travels alone like an alienated mote across her occupied homeland in a rented car, the possibility of violence looms at every turn. None of this reads like crime fiction or a thriller. It reads like doom itself, recast as sarcasm.

The woman decides to take the outlandish risk to borrow a colleague’s green ID, and illegally cross from Ramallah into Israeli territory to track down more information. What follows is a somewhat implausible picaresque journey across multiple checkpoints into Israeli museums, archives, and settlements. Shibli ironically deploys and subverts the trope of the obsessed investigator who must find out what happened at all cost.

Over the course of Part 2, Shibli provides a vivisection of the absurd color-coded Apartheid system with its cruel labyrinth of rules and regulations that apply only to Palestinians. Everything is dislocation and estrangement. The maps have all been changed. As the narrator travels alone like an alienated mote across her occupied homeland in a rented car, the possibility of violence looms at every turn. None of this reads like crime fiction or a thriller. It reads like doom itself, recast as sarcasm.

The surface landscape of historic Palestine has been transformed by decades of colonization, yet beneath the trappings of Zionist development linger the traces of what used to be. As “minor details” from Part 1 find their way into the unsettling texture of Part 2 (a barking dog, a spider, abandoned camels), we become increasingly aware that, unbeknownst to her, the narrator is being forced to contend with the same inscrutable web of signs and symbols that governed Part 1. As she ventures closer to the scene of the original crime, the symmetry between her story and that of the Bedouin girl begin to merge.

One key to the uncanny power of the book is its restraint at the level of the sentence and the deceptively simple structure with its two distinct protagonists. The Israeli officer and the Palestinian woman know nothing of each other’s circumstances, but we do. By reading the contrasting narrations side by side, we are urged to make meaning by attending to the ways that the sections reflect and refract each other. In Part 1 the voiceless Bedouin girl is silent, dehumanized, referred to as an absence, but in the warped mirror of Part 2, her double is also her opposite. The novel thus charts two lines: the shift in consciousness between the Nakba era and contemporary times, but also the trajectory that remains constant: racist violence.

Defying conventions of 21st century “characterization” and “humanizing detail,” both the officer and the researcher remain unnamed, and the text is almost completely devoid of dialogue. The nearly silent, anonymous characters who perform detailed actions serve to emphasize the praxis of patriarchal settler colonialism in which the colonizer remains in control of the physical terrain as well as the psychic space. “Personality” is stripped out and the mechanics of the apparatus are laid bare.

The precision of the lens, the lack of sentimentality, the absence of petty authorial intrusion—all these qualities lend the novel its archetypal and allegorical quality. They also point to emotions more tender than outrage, namely heart-stopping affliction and grief. In this way Minor Detail is reminiscent of the French Marxist-Catholic philosopher Simone Weil’s confounding essay “Human Personality” in which she asserts that only that which is “impersonal” is sacred. The only thing that counts in her Platonic calculus is the human element that remains after all ego, all personality, and all that is incidental has been stripped away.

In addition to Weil, Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar comes to mind as does the Palestinian cartoonist Naji-al Ali. After facing four decades of brutality, his iconic character Hanthala simply has no words left to speak. His greatest power is in facelessly bearing witness with his hands clasped behind his back

In one of the book jacket blurbs Indian novelist Meena Kandasamy calls Minor Detail the “political novel we have all been waiting for.” It is exactly this. The novel is political in way it exposes power imbalances that have been implemented by political forces, but it does not situate itself within the usual protest literature topography. Shibli conscientiously avoids most nationalist symbols, charting a distinct course where the political content is sublimated into the form.

Shibli seems to have disinvested from the hyper-charged task of a “representing Palestine” or “moving readers” or “sounding the alarms,” and instead offers a contemplative examination of the workings of language, power, and violence. Minor Detail is not written about the occupation, but rather from the occupation, and stands as a chilling, quiet corrective to the political novel that is saturated in unbearable expressions of trauma.

Shibli’s originality is to have allowed herself to not represent pain, but to language it. The pain and grief of such loss reveal themselves in a slow and steady leak on the page. As in language, as in poetry, as in flesh, Palestine is yet again a woman in this unforgettable work of fiction that quietly attunes the senses to all that is unspeakably criminal in the human world.

[1] I put the word infiltrator in quotation marks, unlike the New York Review of Books, unlike The New York Times, unlike the original Ha’aretz article. Because these publications do not put the word into quotation marks, they reveal an implicit unwillingness to challenge the assumptions of history written by the colonizer.