Dana Goldstein, whose thoughtful condemnation of the Gaza slaughter after years of reserve I celebrate, is a little uncomfortable with the embrace. She points out that I have identified myself as a non- or anti-Zionist, and says that anti-Zionism is redolent of antisemitism. She's a post-Zionist, she says. Goldstein's comments deserve a response, especially at this moment in intellectual life, when so many people are crowding the doorways of this conversation (they turned away 500 people at the University of Chicago Thursday!).

I used to say post- or non- to avoid being negative. Playwright David Zellnik told me that anti-Zionist felt like denying Israel's considerable achievements and I was under David's kind influence on that point. Now I've come to say that I'm an anti-Zionist for several reasons.

First, perhaps most important: My feelings are not neutral about Zionism; I don't like it. I find that I think about it a lot and there is nothing I can really embrace in it outside of the Jewish pride and the historical significance of it and its visionary component. All these elements have lost their value: Zionism privileges Jews and justifies oppression, and this appalls me. Saying I'm anti-Zionist is a sincere expression of my pluralist, minority-respecting worldview. (Here's my back-of-the-envelope description of Zionism, by the way).

Second, Post-Zionist strikes me as an evasion. At this moment, Zionism reigns in historical Palestine and in American Jewry. To say you're a post-Zionist is like saying you're a post-Communist during the Stalin purges. You are tastefully separating yourself from the world, dainty as an English person drinking tea with their little finger separated from the teacup handle. Zionism is a very powerful force in world affairs, certainly Middle East and American society. It is not helpful to one's own thinking or to others who are trying to understand these matters to evade this fact or suggest that post-Zionism is actually a real factor in, say, the life of Gaza City. I urge my readers and others to take a stand if they find Zionist beliefs that so privilege 6 million Jews over 5-6 million non-Jews and that have entailed apartheid and ethnic cleansing a supportable ideology, especially in the age of our mutt president-to-be.

Third, anti-Zionism is a great idealistic Jewish tradition. I have said that anti-Zionism is the new Zionism. It draws on the same visionary and If-you-dream-it feeling that Zionism did 100 years ago, before the militants ruined it, and engages the same young restless sensibilities and liberationist feeling as Zionism did. We anti-Zionists can say with honor that great Jewish anti-Zionists like Rabbi Elmer Berger identified the problems with Zionism 60 years ago, accurately, and Jack Ross who is biographing Berger continues that in his bold youth: Berger said that Zionism meant contempt for the Arab population, dependence on a backroom lobby in the United States, and the introduction of dual loyalty into American Jewish life. All true. Hannah Arendt and Walter Benjamin and Norman Mailer all opposed Zionism to one degree or another out of ethnocentric concerns. Didn't like the Is-it-good-for-the-Jews stuff. These problems are larger today than ever, especially post-Iraq and Iraq's idiot stepson, Gaza.

Finally, saying I'm anti-Zionist is my way of trying to make room in American life for this view, just as American intellectual life had room for anti-Communism, socialism, and Communism too, when I was little. Being critical of Zionism means that you can hurt your business, as the San Francisco Chronicle has reported. This is true and disgusting. As Jimi Hendrix said when he was changing America: I'm going to wave my freak flag high!

The antisemitism point. The American Jewish Committee has said the same thing, of course: anti-Zionism is antisemitism. It would thus conflate Jewishness with Zionism. A conflation that is damaging Jewish experience around the world. When Dana says it, I feel a hovering penumbra of censoriousness. There are things you can and can't say. Well I am an empowered Jew who has never experienced functional antisemitism ever in my life, and that too is important, my empowerment: I insist on speaking about Jewish cultural/financial power in the U.S. as a component of my Zionist critique. Do I think that Jews should be denied power? No! Do I think that there should be quotas on Jewish inclusion in elite institutions? No! Well: I would like Jewish participation in mainstream media roundtables on the Middle East held to 50 percent or lower. That is my quota. These ideas–including my description of Jewish place in the Establishment and the underrepresentation of Jews in the military– have made some readers uncomfortable. They've made me uncomfortable. I grew up in fear of lurking antisemitism. I have decided in my 50s that these are things I think about all the time as a mature person, however intellectually and emotionally flawed I am, and so I am going to talk about them come what may because I think they're important.

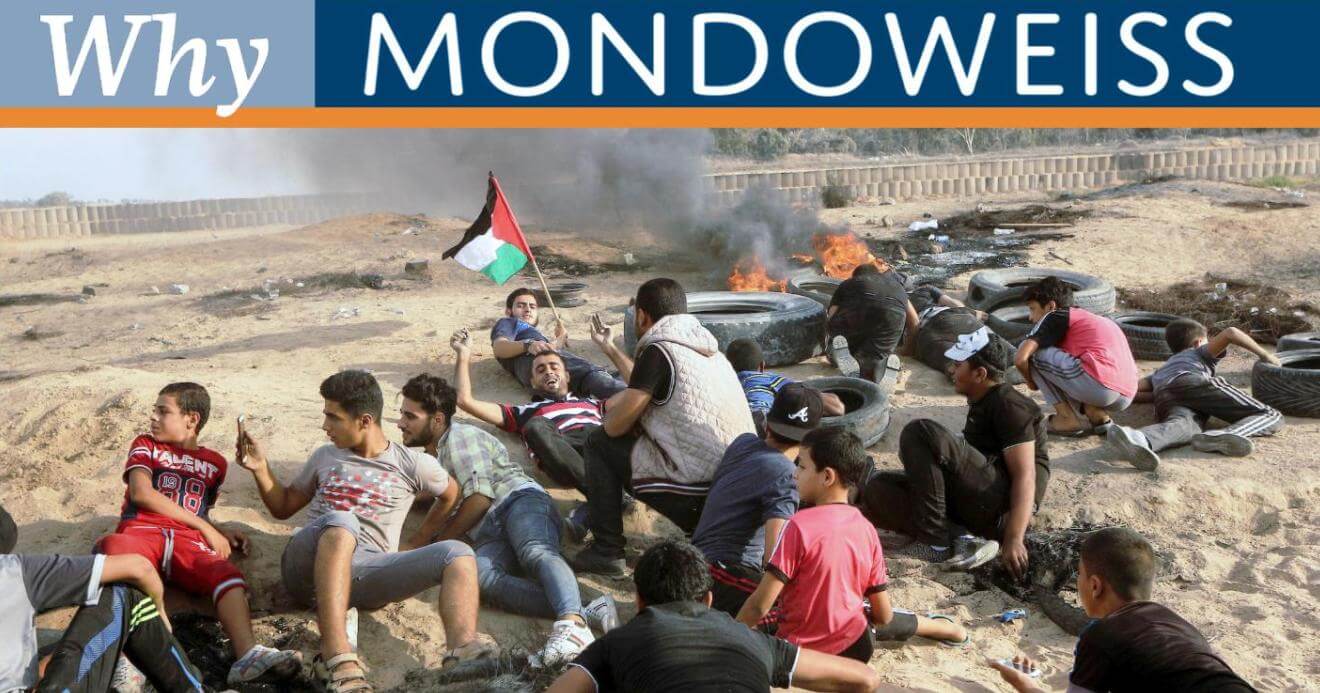

And I would add that shutting down debate in the name of "antisemitism" strikes me as selfish. Our phantom worries about a second Holocaust take precedence over the real evidence that surrounds us of man's inhumanity to man, not just man's inhumanity to Jews. And our phantom worries mean that we cannot address the incredible, everyday, real suffering of Palestinians that has been perpetrated politically in large part by empowered American Jews who are all over the media and political establishment, some of whom limit debate of the issue by citing a possible infraction of our tremendous freedoms. Believe me, when our freedoms are encroached upon, I will howl. Today and tomorrow I howl for the Jewish leadership's actual crushing of the Palestinian right of self-determination.